Posts Tagged Music

Building a music map

Posted by Paul in data, fun, java, Music, research, The Echo Nest, visualization, web services on May 31, 2009

I like maps, especially maps that show music spaces – in fact I like them so much I have one framed, hanging in my kitchen. I’d like to create a map for all of music. Like any good map, this map should work at multiple levels; it should help you understand the global structure of the music space, while allowing you to dive in and see fine detailed structure as well. Just as Google maps can show you that Africa is south of Europe and moments later that Stark st. intersects with Reservoir St in Nashua NH a good music map should be able to show you at a glance how Jazz, Blues and Rock relate to each other while moments later let you find an unknown 80s hair metal band that sounds similar to Bon Jovi.

My goal is to build a map of the artist space, one the allows you to explore the music space at a global level, to understand how different music styles relate, but then also will allow you to zoom in and explore the finer structure of the artist space.

I’m going to base the music map on the artist similarity data collected from the Echo Nest artist similarity web service. This web service lets you get 15 most similar artists for any artist. Using this web service I collected the artist similarity info for about 70K artists along with each artists familiarity and hotness.

Some Explorations

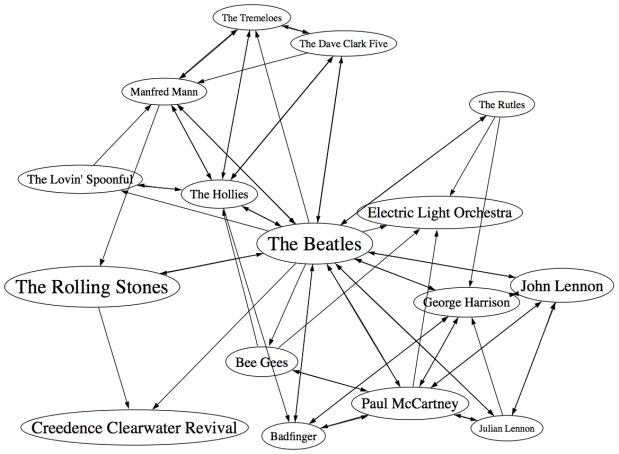

It would be silly to start trying to visualize 70K artists right away – the 250K artist-to-artist links would overwhelm just about any graph layout algorithm. The graph would look like this. So I started small, with just the near neighbors of The Beatles. (Beatles-K1) For my first experiment, I graphed the the nearest neighbors to The Beatles. This plot shows how the the 15 near neighbors to the Beatles all connect to each other.

In the graph, artist names are sized proportional to the familiarity of the artist. The Beatles are bigger than The Rutles because they are more familiar. I think the graph is pretty interesting, showing how all of the similar artists of the Beatles relate to each other, however, the graph is also really scary because it shows 64 interconnections for these 16 artists. This graph is just showing the outgoing links for the Beatles, if we include the incoming links to the Beatles (the artist similarity function is asymettric so outgoing similarities and incoming similarities are not the same), it becomes a real mess:

If you extend this graph one more level – to include the friends of the friends of The Beatles (Beatles-K2), the graph becomes unusable. Here’s a detail, click to see the whole mess. It is only 116 artists with 665 edges, but already you can see that it is not going to be usable.

Eliminating the edges

Clearly the approach of drawing all of the artist connections is not going to scale to beyond a few dozen artists. One approach is to just throw away all of the edges. Instead of showing a graph representation, use an embedding algorithm like MDS or t-SNE to position the artists in the space. These algorithms layout items by attempting to minimize the energy in the layout. It’s as if all of the similar items are connected by invisible springs which will push all of the artists into positions that minimize the overall tension in the springs. The result should show that similar artists are near each other, and dissimilar artists are far away. Here’s a detail for an example for the friends of the friends of the Beatles plot. (Click on it to see the full plot)

I find this type of visualization to be quite unsatisfying. Without any edges in the graph I find it hard to see any structure. I think I would find this graph hard to use for exploration. (Although it is fun though to see the clustering of bands like The Animals, The Turtles, The Byrds, The Kinks and the Monkeee).

Drawing some of the edges

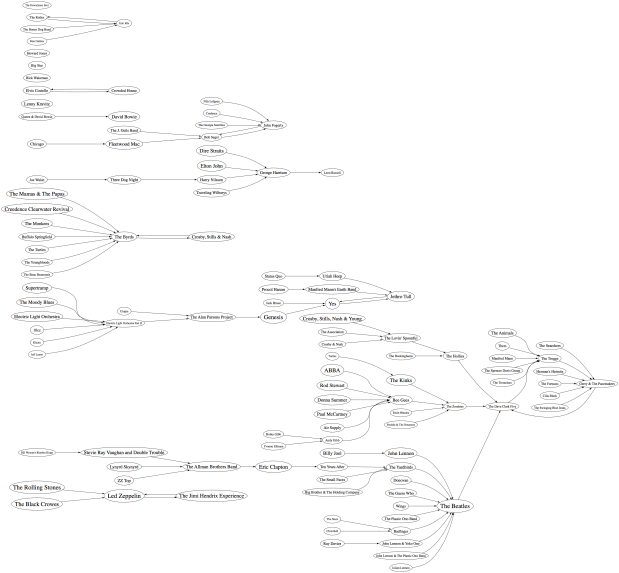

We can’t draw all of the edges, the graph just gets too dense, but if we don’t draw any edges, the map loses too much structure making it less useful for exploration. So lets see if we can only draw some of the edges – this should bring back some of the structure, without overwhelming us with connections. The tricky question is “Which edges should I draw?”. The obvious choice would be to attach each artist to the artist that it is most similar to. When apply this to the Beatles-K2 neighborhood we get something like this:

This clearly helps quite a bit. We no longer have the bowl of spaghetti, while we can still see some structure. We can even see some clustering that make sense (Led Zeppelin is clustered with Jimi Hendrix and the Rolling Stones while Air Supply is closer to the Bee Gees). But there are some problems with this graph. First, it is not completely connected, there are a 14 separate clusters varying from a size of 1 to a size of 57. This disconnection is not really acceptable. Second, there are a number of non-intuitive flows from familiar to less familiar artists. It just seems wrong that bands like the Moody Blues, Supertramp and ELO are connected to the rest of the music world via Electric Light Orchestra II (shudder).

To deal with the ELO II problem I tried a different strategy. Instead of attaching an artist to its most similar artist, I attach it to the most similar artist that also has the closest, but greater familiarity. This should prevent us from attaching the Moody Blues to the world via ELO II, since ELO II is of much less familiarity than the Moody Blues. Here’s the plot:

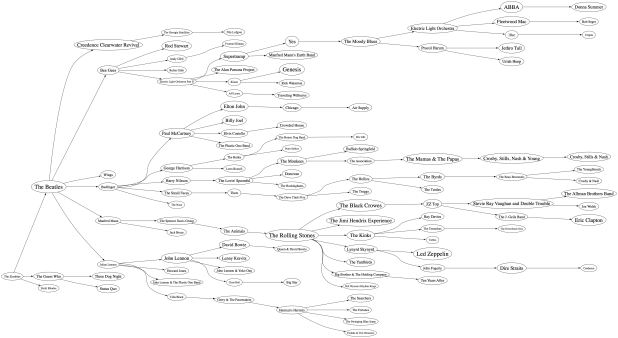

Now we are getting some where. I like this graph quite a bit. It has a nice left to right flow from popular to less popular, we are not overwhelmed with edges, and ELO II is in its proper subservient place. The one problem with the graph is that it is still disjoint. We have 5 clusters of artists. There’s no way to get to ABBA from the Beatles even though we know that ABBA is a near neighbor to the Beatles. This is a direct product of how we chose the edges. Since we are only using some of the edges in the graph, there’s a chance that some subgraphs will be disjoint. When I look at the a larger neighborhood (Beatles-K3), the graph becomes even more disjoint with a hundred separate clusters. We want to be able to build a graph that is not disjoint at all, so we need a new way to select edges.

Minimum Spanning Tree

One approach to making sure that the entire graph is connected is to generate the minimum spanning tree for the graph. The minimum spanning tree of a graph minimizes the number of edges needed to connect the entire graph. If we start with a completely connected graph, the minimum spanning tree is guarantee to result in a completely connected graph. This will eliminate our disjoint clusters. For this next graph, built the minimum spanning tree of the Beatles-K2 graph.

As predicted, we no longer have separate clusters within the graph. We can find a path between any two artists in the graph. This is a big win, we should be able to scale this approach up to an even larger number of artists without ever having to worry about disjoint clusters. The whole world of music is connected in a single graph. However, there’s something a bit unsatisfying about this graph. The Beatles are connected to only two other artists: John Lennon & The Plastic Ono Band and The Swinging Blue Jeans. I’ve never heard of the Swinging Blue Jeans. I’m sure they sound a lot like the Beatles, but I’m also sure that most Beatles fans would not tie the two bands together so closely. Our graph topology needs to be sensitive to this. One approach is to weight the edges of the graph differently. Instead of weighting them by similarity, the edges can be weighted by the difference in familiarity between two artists. The Beatles and Rolling Stones have nearly identical familiarities so the weight between them would be close to zero, while The Beatles and the Swinging Blue Jeans have very different familiarities, so the weight on the edge between them would be very high. Since the minimum spanning is trying to reduce the overall weight of the edges in the graph, it will chose low weight edges before it chooses high weight edges. The result is that we will still end up with a single graph, with none of the disjoint clusters, but artists will be connected to other artists of similar familiarity when possible. Let’s try it out:

Now we see that popular bands are more likely to be connected to other popular bands, and the Beatles are no longer directly connected to “The Swinging Blue Jeans”. I’m pretty happy with this method of building the graph. We are not overwhelmed by edges, we don’t get a whole forest of disjoint clusters, and the connections between artists makes sense.

Of course we can build the graph by starting from different artists. This gives us a deep view into that particular type of music. For instance, here’s a graph that starts from Miles Davis:

Here’s a near neighbor graph starting from Metallica:

And here’s one showing the near neighbors to Johann Sebastian Bach:

This graphing technique works pretty well, so lets try an larger set of artists. Here I’m plotting the top 2,000 most popular artists. Now, unlike the Beatles neighborhood, this set of artists is not guaranteed to be connected, so we may have some disjoint cluster in the plot. That is expected and reasonable. The image of the resulting plot is rather large (about 16MB) so here’s a small detail, click on the image to see the whole thing. I’ve also created a PDF version which may be easier to browse through.

I pretty pleased with how these graphs have turned out. We’ve taken a very complex space and created a visualization that shows some of the higher level structure of the space (jazz artists are far away from the thrash artists) as well as some of the finer details – the female bubblegum pop artists are all near each other. The technique should scale up to even larger sets of artists. Memory and compute time become the limiting factors, not graph complexity. Still, the graphs aren’t perfect – seemingly inconsequential artists sometimes appear as gateways into whole sub genre. A bit more work is needed to figure out a better ordering for nodes in the graph.

Some things I’d like to try, when I have a bit of spare time:

- Create graphs with 20K artists (needs lots of memory and CPU)

- Try to use top terms or tags of nearby artists to give labels to clusters of artists – so we can find the Baroque composers or the hair metal bands

- Color the nodes in a meaningful way

- Create dynamic versions of the graph to use them for music exploration. For instance, when you click on an artist you should be able to hear the artist and read what people are saying about them.

To create these graphs I used some pretty nifty tools:

- The Echo Nest developer web services – I used these to get the artist similarity, familiarity and hotness data. The artist similarity data that you get from the Echo Nest is really nice. Since it doesn’t rely directly on collaborative filtering approaches it avoids the problems I’ve seen with data from other sources of artist similarity. In particular, the Echo Nest similarity data is not plagued by hubs (for some music services, a popular band like Coldplay may have hundreds or thousands of near neighbors due to a popularity bias inherent in CF style recommendation). Note that I work at the Echo Nest. But don’t be fooled into thinking I like the Echo Nest artist similarity data because I work there. It really is the other way around. I decided to go and work at the Echo Nest because I like their data so much.

- Graphviz – a tool for rendering graphs

- Jung – a Java library for manipulating graphs

If you have any ideas about graphing artists – or if you’d like to see a neighborhood of a particular artist. Please let me know.

I may never use iTunes again

On the Spotify blog there’s a video demo of Spotify running on Android (the Google mobile OS). This is a demo of work-in-progress, but already it shows that just as Spotify is pushing the bounds on the desktop, they are going to push the bounds on mobile devices. The demo shows that you get the full Spotify experience on your device. You can listen to just about any song by any artist. No waiting for music to load, it just starts playing right away. All your Spotify playlists are available on your device. You don’t have to do that music shuffle game that you play with the iPod – where you have to decide on Sunday what songs you will want to listen to on Tuesday.

On the Spotify blog there’s a video demo of Spotify running on Android (the Google mobile OS). This is a demo of work-in-progress, but already it shows that just as Spotify is pushing the bounds on the desktop, they are going to push the bounds on mobile devices. The demo shows that you get the full Spotify experience on your device. You can listen to just about any song by any artist. No waiting for music to load, it just starts playing right away. All your Spotify playlists are available on your device. You don’t have to do that music shuffle game that you play with the iPod – where you have to decide on Sunday what songs you will want to listen to on Tuesday.

I think the killer feature in the demo is offline syncing. You can make any playlist available for listening even when you are offline. When you mark a playlist for offline sync, the tracks in the playlist are downloaded to your device allowing you to listen to them in those places that have no Internet connection (such as a plane, the subway or Vermont). The demo also shows how Spotify keeps all your playlists magically in sync. Add a song to one of your Spotify playlists while sitting at your computer and the corresponding playlist on your device is instantly updated. Totally cool. I do worry that the record labels may balk at the offline sync feature. Spotify may be pushing the bounds further than the labels want to go, by letting us listen to any music at any time, whether at home, in the office or mobile.

Much of my daily music listening is now through the Spotify desktop client. The folks at Spotify continue to add music at a phenomenal rate (100K new tracks in the last week). The only reason I ever fire up iTunes now is to synchronize music to my iPhone. It is no secret that Spotify is also working on an iPhone version of their mobile app. I can’t wait to get a hold of it. When that happens, I may never use iTunes again.

Check out the demo:

Artist similarity, familiarity and hotness

Posted by Paul in Music, recommendation, The Echo Nest, visualization, web services on May 25, 2009

The Echo Nest developer web services offer a number of interesting pieces of data about an artist, including similar artists, artist familiarity and artist hotness. Familiarity is an indication of how well known the artist is, while hotness (which we spell as the zoolanderish ‘hotttnesss’) is an indication of how much buzz the artist is getting right now. Top familiar artists are band like Led Zeppelin, Coldplay, and The Beatles, while top ‘hottt’ artists are artists like Katy Perry, The Boy Least Likely to, and Mastodon.

The Echo Nest developer web services offer a number of interesting pieces of data about an artist, including similar artists, artist familiarity and artist hotness. Familiarity is an indication of how well known the artist is, while hotness (which we spell as the zoolanderish ‘hotttnesss’) is an indication of how much buzz the artist is getting right now. Top familiar artists are band like Led Zeppelin, Coldplay, and The Beatles, while top ‘hottt’ artists are artists like Katy Perry, The Boy Least Likely to, and Mastodon.

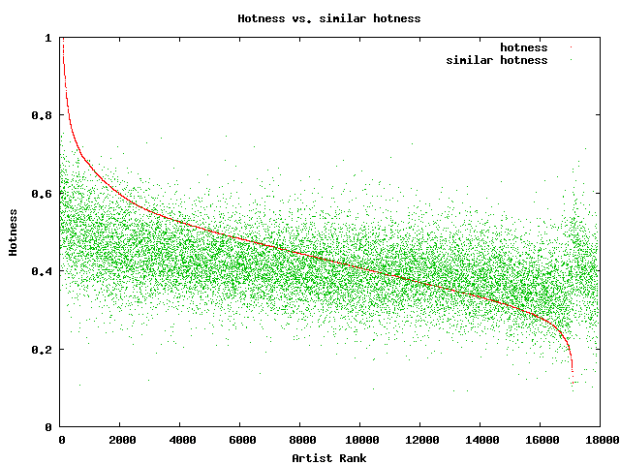

I was interested in understanding how familiarity, hotness and similarity interact with each other, so I spent my Memorial day morning creating a couple of plots to help me explore this. First, I was interested in learning how the familiarity of an artist relates to the familiarity of that artists’s similar artists. When you get the similar artists for an artist, is there any relationship between the familiarity of these similar artists and the seed artist? Since ‘similar artists’ are often used for music discovery, it seems to me that on average, the similar artists should be less familiar than the seed artist. If you like the very familiar Beatles, I may recommend that you listen to ‘Bon Iver’, but if you like the less familiar ‘Bon Iver’ I wouldn’t recommend ‘The Beatles’. I assume that you already know about them. To look at this, I plotted the average familiarity for the top 15 most similar artists for each artist along with the seed artist’s familiarity. Here’s the plot:

In this plot, I’ve take the top 18,000 most familiar artists, ordered them by familiarity. The red line is the familiarity of the seed artist, and the green cloud shows the average familiarity of the similar artists. In the plot we can see that there’s a correlation between artist familiarity and the average familiarity of similar artists. We can also see that similar artists tend to be less familiar than the seed artist. This is exactly the behavior I was hoping to see. Our similar artist function yields similar artists that, in general, have an average famililarity that is less than the seed artist.

In this plot, I’ve take the top 18,000 most familiar artists, ordered them by familiarity. The red line is the familiarity of the seed artist, and the green cloud shows the average familiarity of the similar artists. In the plot we can see that there’s a correlation between artist familiarity and the average familiarity of similar artists. We can also see that similar artists tend to be less familiar than the seed artist. This is exactly the behavior I was hoping to see. Our similar artist function yields similar artists that, in general, have an average famililarity that is less than the seed artist.

This plot can help us q/a our artist similarity function. If we see the average familiarity for similar artists deviates from the standard curve, there may be a problem with that particular artist. For instance, T-Pain has a familiarity of 0.869, while the average familiarity of T-Pain’s similar artists is 0.340. This is quite a bit lower than we’d expect – so there may be something wrong with our data for T-Pain. We can look at the similars for T-Pain and fix the problem.

For hotness, the desired behavior is less clear. If a listener starting from a medium hot artist is looking for new music, it is unclear whether or not they’d like a hotter or colder artist. To see what we actually do, I looked at how the average hotness for similar artists compare to the hotness of the seed artist. Here’s the plot:

In this plot, the red curve is showing the hotness of the top 18,000 most familiar artists. It is interesting to see the shape of the curve, there are very few ultra-hot artists (artists with a hotness about .8) and very few familiar, ice cold artists (with a hotness of less than 0.2). The average hotness of the similar artists seems to be somewhat correlated with the hotness of the seed artist. But markedly less than with the familiarity curve. For hotness if your seed artist is hot, you are likely to get less hot similar artists, while if the seed artist is not hot, you are likely to get hotter artists. That seems like reasonable behavior to me.

In this plot, the red curve is showing the hotness of the top 18,000 most familiar artists. It is interesting to see the shape of the curve, there are very few ultra-hot artists (artists with a hotness about .8) and very few familiar, ice cold artists (with a hotness of less than 0.2). The average hotness of the similar artists seems to be somewhat correlated with the hotness of the seed artist. But markedly less than with the familiarity curve. For hotness if your seed artist is hot, you are likely to get less hot similar artists, while if the seed artist is not hot, you are likely to get hotter artists. That seems like reasonable behavior to me.

Well, there you have it. Some Monday morning explorations of familiarity, similarity and hotness. Why should you care? If you are building a music recommender, familiarity and hotness are really interesting pieces of data to have access to. There’s a subtle game a recommender has to play, it has to give a certain amount of familiar recommendations to gain trust, while also giving a certain number of novel recommendations in order to enable music discovery.

Spotify + Echo Nest == w00t!

Posted by Paul in Music, The Echo Nest, web services on May 19, 2009

Yesterday, at the SanFran MusicTech Summit, I gave a sneak preview that showed how Spotify is tapping into the Echo Nest platform to help their listeners explore for and discover new music. I must say that I am pretty excited about this. Anyone who has read this blog and its previous incarnation as ‘Duke Listens!’ knows that I am a long time enthusiast of Spotify (both the application and the team). I first blogged about Spotify way back in January of 2007 while they were still in stealth mode. I blogged about the Spotify haircuts, and their serious demeanor:

Yesterday, at the SanFran MusicTech Summit, I gave a sneak preview that showed how Spotify is tapping into the Echo Nest platform to help their listeners explore for and discover new music. I must say that I am pretty excited about this. Anyone who has read this blog and its previous incarnation as ‘Duke Listens!’ knows that I am a long time enthusiast of Spotify (both the application and the team). I first blogged about Spotify way back in January of 2007 while they were still in stealth mode. I blogged about the Spotify haircuts, and their serious demeanor:

I blogged about the Spotify application when it was released to private beta: Woah – Spotify is pretty cool, and continued to blog about them every time they added another cool feature.

I’ve been a daily user of Spotify for 18 months now. It is one of my favorite ways to listen to music on my computer. It gives me access to just about any song that I’d like to hear (with a few notable exceptions – still no Beatles for instance).

It is clear to anyone who uses Spotify for a few hours that having access to millions and millions of songs can be a bit daunting. With so many artists and songs to chose from, it can be hard to decide what to listen to – Barry Schwartz calls this the Paradox of Choice – he says too many options can be confusing and can create anxiety in a consumer. The folks at Spotify understand this. From the start they’ve been building tools to help make it easier for listeners to find music. For instance, they allow you to easily share playlists with your friends. I can create a music inbox playlist that any Spotify user can add music to. If I give the URL to my friends (or to my blog readers) they can add music that they think I should listen to.

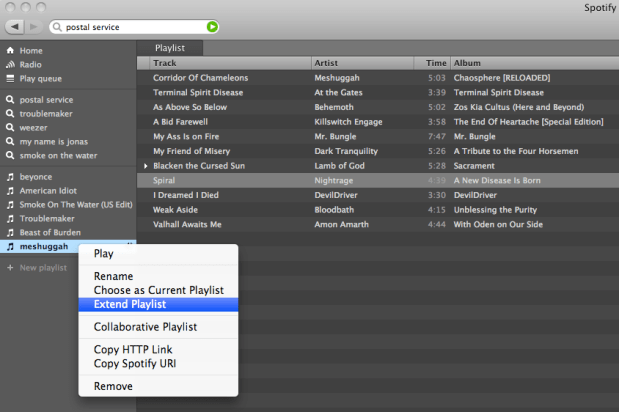

Now with the Spotify / Echo Nest connection, Spotify is going one step further in helping their listeners deal with the paradox of choice. They are providing tools to make it easier for people to explore for and discover new music. The first way that Spotify is tapping in to the Echo Nest platform is very simple, and intuitive. Right click on a playlist, and select ‘Extend Playlist’. When you do that, the playlist will automatically be extended with songs that fit in well with songs that are already in the playlist. Here’s an example:

So how is this different from any other music recommender? Well, there are a number of things going on here. First of all, most music recommenders rely on collaborative filtering (a.k.a. the wisdom of the crowds), to recommend music. This type of music recommendation works great for popular and familiar artists recommendations … if you like the Beatles, you may indeed like the Rolling Stones. But Collaborative Filtering (CF) based recommendations don’t work well when trying to recommend music at the track level. The data is often just to sparse to make recommendations. The wisdom of the crowds model fails when there is no crowd. When one is dealing with a Spotify-sized music collection of many millions of songs, there just isn’t enough user data to give effective recommendations for all of the tracks. The result is that popular tracks get recommended quite often, while less well known music is ignored. To deal with this problem many CF-based recommenders will rely on artist similarity and then select tracks at random from the set of similar artists. This approach doesn’t always work so well, especially if you are trying to make playlists with the recommender. For example, you may want a playlist of acoustic power ballads by hair metal bands of the 80s. You could seed the playlist with a song like Mötley Crüe’s Home Sweet Home, and expect to get similar power ballads, but instead you’d find your playlist populated with standard glam metal fair, with only a random chance that you’d have other acoustic power ballads. There are a boatload of other issues with wisdom of the crowds recommendations – I’ve written about them previously, suffice it to say that it is a challenge to get a CF-based recommender to give you good track-level recommendations.

The Echo Nest platform takes a different approach to track-level recommendation. Here’s what we do:

- Read and understand what people are saying about music – we crawl every corner of the web and read every news article, blog post, music review and web page for every artist, album and track. We apply statistical and natural language processing to extract meaning from all of these words. This gives us a broad and deep understanding of the global online conversation about music

- Listen to all music – we apply signal processing and machine learning algorithms to audio to extract a number perceptual features about music. For every song, we learn a wide variety of attributes about the song including the timbre, song structure, tempo, time signature, key, loudness and so on. We know, for instance, where every drum beat falls in Kashmir, and where the guitar solo starts in Starship Trooper.

- We combine this understanding of what people are saying about music and our understanding of what the music sounds like to build a model that can relate the two – to give us a better way of modeling a listeners reaction to music. There’s some pretty hardcore science and math here. If you are interested in the gory details, I suggest that you read Brian’s Thesis: Learning the meaning of music.

What this all means is that with the Echo Nest platform, if you want to make a playlist of acoustic hair metal power ballads, we’ll be able to do that – we know who the hair metal bands are, and we know what a power ballad sounds like. And since we don’t rely on the wisdom of the crowds for recommendation we can avoid some of the nasty problems that collaborative filtering can lead to. I think that when people get a chance to play with the ‘Extend Playlist’ feature they’ll be happy with the listening experience.

It was great fun giving the Spotify demo at the SanFran MusicTech Summit. Even though Spotify is not available here in the U.S., the buzz that is occuring in Europe around Spotify is leaking across the ocean. When I announced that Spotify would be using the Echo Nest, there’s was an audible gasp from the audience. Some people were seeing Spotify for the first time, but everyone knew about it. It was great to be able to show Spotify using the Echo Nest. This demo was just a sneak preview. I expect there will be lots more interestings to come. Stay tuned.

SanFran Music Tech summit

Posted by Paul in recommendation, The Echo Nest, web services on May 13, 2009

This weekend I’ll be heading out to San Francisco to attend the SanFran MusicTech Summit. The summit is a gathering of musicians, suits, lawyers, and techies with a focus on the convergence of music, business, technology and the law. There’s quite a set of music tech luminaries that will be in attendance, and the schedule of panels looks fantastic.

I’ll be moderating a panel on Music Recommendation Services. There are some really interesting folks on the panel: Stephen White from Gracenote, Alex Lascos from BMAT, James Miao from the Sixty One and Michael Papish from Media Unbound. I’ve been on a number of panels in the last few years. Some have been really good, some have been total train wrecks. The train wrecks occur when (1) panelists have an opportunity to show powerpoint slides, (2) a business-oriented panelist decides that the panel is just another sales call, (3) the moderator loses control and the panel veers down a rat hole of irrelevance. As moderator, I’ll try to make sure the panel doesn’t suck .. but already I can tell from our email exchanges that this crew will be relevant, interesting and funny. I think the panel will be worth attending.

We are already know some of the things that we want to talk about in the panel:

- Does anyone really have a problem finding new music? Is this a problem that needs to be solved?

- What makes a good music recommendation?

- What’s better – a human or a machine recommender?

- Problems in high stakes evaluations

And some things that we definitely do not want to talk about:

- Business models

- Music industry crisis

If you are attending the summit, I hope you’ll attend the panel.

79 Versions of Popcorn, remixed.

Posted by Paul in Music, remix, The Echo Nest on May 1, 2009

Aaron Meyer’s issued a challenge for someone to remix 79 versions of the song Popcorn. So I fired up one of the remix applications that Tristan and Brian wrote a while back that uses our remix API to stitch all 79 versions of Popcorn together into one 12 minute track – songs are beat matched, tempos are stretched and beats are aligned to form a single seamless (well, almost seamless) version of the Hot Buttered classic. I’m interested to hear what some of the other computational remixologists could do with this challenge. Everyone, stop writing your thesis, and make some popcorn!

Aaron Meyer’s issued a challenge for someone to remix 79 versions of the song Popcorn. So I fired up one of the remix applications that Tristan and Brian wrote a while back that uses our remix API to stitch all 79 versions of Popcorn together into one 12 minute track – songs are beat matched, tempos are stretched and beats are aligned to form a single seamless (well, almost seamless) version of the Hot Buttered classic. I’m interested to hear what some of the other computational remixologists could do with this challenge. Everyone, stop writing your thesis, and make some popcorn!

Listen:

Download: A Kettle of Echo Nest Popcorn.

If you are interested in creating your own remix, check out the Echo Nest API and the Echo Nest Remix SDK. (Thanks Andy, for the tip!).

The Free Music Archive

Posted by Paul in Music, recommendation, startup on April 20, 2009

Last week The Free Music Archive opened its virtual doors offering thousands of free tracks for streaming or download. Yes, there are tons of sites on the web that offer new music for free, but the FMA is different. The music on the FMA is curated by music experts (radio programmers, webcasters, venues, labels, collectives and so on) – so that instead of a slush pile dominated by bad music typical of other free music sites, the music at the FMA is really good (or at least one human expert thinks it is good). Most of the music on the FMA is released under some form of a Creative Commons license that allows for free non-commercial use making it suitable for you to use in your podcast, remix, video game or MIR research.

Last week The Free Music Archive opened its virtual doors offering thousands of free tracks for streaming or download. Yes, there are tons of sites on the web that offer new music for free, but the FMA is different. The music on the FMA is curated by music experts (radio programmers, webcasters, venues, labels, collectives and so on) – so that instead of a slush pile dominated by bad music typical of other free music sites, the music at the FMA is really good (or at least one human expert thinks it is good). Most of the music on the FMA is released under some form of a Creative Commons license that allows for free non-commercial use making it suitable for you to use in your podcast, remix, video game or MIR research.

For free-music aggregation sites like the FMA, music discovery has always been a big challenge. Without any well-known artists to use as starting points into the collection, it is hard for a visitor to find music that they might like. The FMA does have and advantage over other free-music aggregators – with the human curator in the loop, you’ll spend less time wading through bad music trying to find the music gems. But the FMA and and other free-music sites need to do whole lot better if they are going to really become sources of new music for people. It would be great if I could go to a site like FMA and tell them about my music tastes (perhaps by giving them a link to my APML, or itunesLibrary.xml or last.fm name) and have them point me to the music in their collection that best matches my music taste. If they could give me a weekly customized music podcast with their newest music that best matches my music taste, I’d be in new-music heaven.

The FMA is pretty neat. I like the human-in-the-loop approach that leads to a high-quality music catalog.

Help! My iPod thinks I’m emo – Part 1

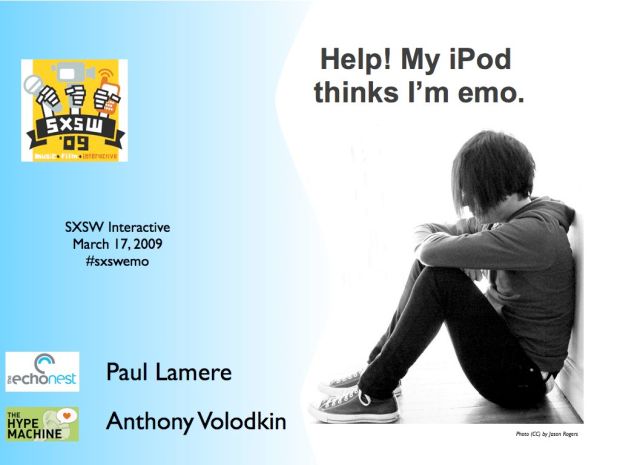

Posted by Paul in Music, recommendation, research, The Echo Nest on March 26, 2009

At SXSW 2009, Anthony Volodkin and I presented a panel on music recommendation called “Help! My iPod thinks I’m emo”. Anthony and I share very different views on music recommendation. You can read Anthony’s notes for this session at his blog: Notes from the “Help! My iPod Thinks I’m Emo!” panel. This is Part 1 of my notes – and my viewpoints on music recommendation. (Note that even though I work for The Echo Nest, my views may not necessarily be the same as my employer).

The SXSW audience is a technical audience to be sure, but they are not as immersed in recommender technology as regular readers of MusicMachinery, so this talk does not dive down into hard core tech issues, instead it is a lofty overview of some of the problems and potential solutions for music recommendation. So lets get to it.

Music Recommendation is Broken.

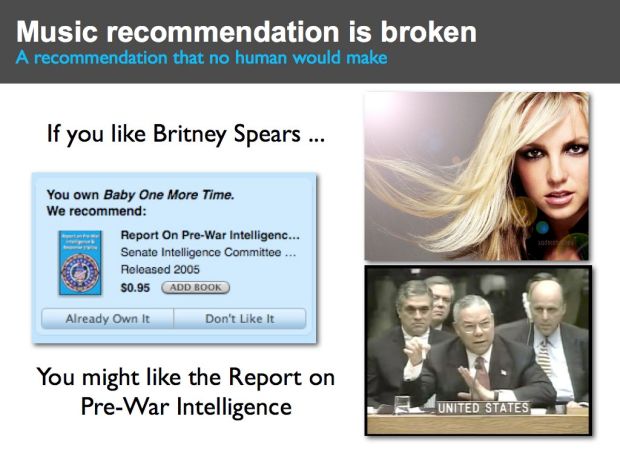

Even though Anthony and I disagree about a number of things, one thing that we do agree on is that music recommendation is broken in some rather fundamental ways. For example, this slide shows a recommendation from iTunes (from a few years back). iTunes suggests that if I like Britney Spears’ “Hit Me Baby One more time” that I might also like the “Report on Pre-War Intelligence for the Iraq war”.

Clearly this is a broken recommendation – this is a recommendation no human would make. Now if you’ve spent anytime visiting music sites on the web you’ve likely seen recommendations just as bad as this. Sometimes music recommenders just get it wrong – and they get it wrong very badly. In this talk we are going to talk about how music recommenders work, why they make such dumb mistakes, and some of the ideas coming from researchers and innovators like Anthony to fix music discovery.

Why do we even care about music recommendation and discovery?

The world of music has changed dramatically. When I was growing up, a typical music store had on the order of 1,000 unique artists to chose from. Now, online music stores like iTunes have millions of unique songs to chose from. Myspace has millions of artists, and the P2P networks have billions of tracks available for download. We are drowning in a sea of music. And this is just the beginning. In a few years time the transformation to digital, online music will be complete. All recorded music will be online – every recording of every performance of every artist, whether they are a mainstream artist or a garage band or just a kid with a laptop will be uploaded to the web. There will be billions of tracks to chose from, with millions more arriving every week. With all this music to chose from, this should be a music nirvana – we should all be listening to new and interesting music.

With all this music, classic long tail economics apply. Without the constraints of physical space, music stores no longer need to focus on the most popular artists. There should be less of a focus on the hits and the megastars. With unlimited virtual space, we should see a flattening of the long tail – music consumption should shift to less popular artists. This is good for everyone. It is good for business – it is probably cheaper for a music store to sell a no-name artist than it is to sell the latest Miley Cyrus track. It is good for the artist – there are millions of unknown artists that deserve a bit of attention, and it is good for the listener. Listeners get to listen to a larger variety of music, that better fits their taste, as opposed to music designed and produced to appeal to the broadest demographics possible. So with the increase in available music we should see less emphasis on the hits. In the future, with all this music, our music listening should be less like Walmart and more like SXSW. But is this really happening? Lets take a look.

The state of music discovery

If we look at some of the data from Nielsen Soundscan 2007 we see that although there were more than 4 million tracks sold only 1% of those tracks accounted for 80% of sales. What’s worse, a whopping 13% of all sales are from American Idol or Disney Artists. Clearly we are still focusing on the hits. One must ask, what is going on here? Was Chris Anderson wrong? I really don’t think so. Anderson says that to make the long tail ‘work’ you have to do two things (1) Make everything available and (2) Help me find it. We are certainly on the road to making everything available – soon all music will be online. But I think we are doing a bad job on step (2) help me find it. Our music recommenders are *not* helping us find music, in fact current music recommenders do the exact opposite, they tend to push us toward popular artists and limit the diversity of recommendations. Music recommendation is fundamentally broken, instead of helping us find music in the long tail they are doing the exact opposite. They are pushing us to popular content. To highlight this take a look at the next slide.

Help! I’m stuck in the head

This is a study done by Dr. Oscar Celma of MTG UPF (and now at BMAT). Oscar was interested in how far into the long tail a recommender would get you. He divided the 245,000 most popular artists into 3 sections of equal sales – the short head, with 83 artists, the mid tail with 6,659 artists, and the long tail with 239,798 artists. He looked at recommendations (top 20 similar artists) that start in the short head and found that 48% of those recommendations bring you right back to the short head. So even though there are nearly a quarter million artists to chose from, 48% of all recommendations are drawn from a pool of the 83 most popular artists. The other 52% of recommendations are drawn from the mid-tail. No recommendations at all bring you to the long tail. The nearly 240,000 artists in the long tail are not reachable directly from the short head. This demonstrates the problem with commercial recommendation – it focuses people on the popular at the expense of the new and unpopular.

Let’s take a look at why recommendation is broken.

The Wisdom of Crowds

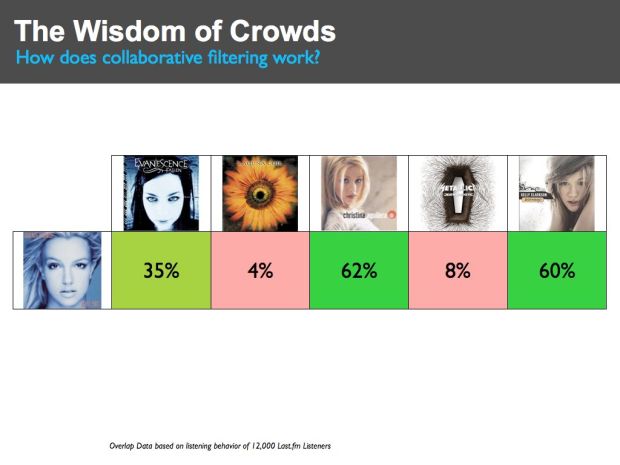

First lets take a look at how a typical music recommender works. Most music recommenders use a technique called Collaborative Filtering (CF). This is the type of recommendation you get at Amazon where they tell you that ‘people who bought X also bought Y’. The core of a CF recommender is actually quite simple. At the heart of the recommender is typically an item-to-item similarity matrix that is used to show how similar or dissimilar items are. Here we see a tiny excerpt of such a matrix. I constructed this by looking at the listening patterns of 12,000 last.fm listeners and looking at which artists have overlapping listeners. For instance, 35% of listeners that listen to Britney Spears also listen to Evancescence, while 62% also listen to Christina Aguilera. The core of a CF recommender is such a similarity matrix constructed by looking at this listener overlap. If you like Britney Spears, from this matrix we could recommend that you might like Christana and Kelly Clarkson, and we’d recommend that you probably wouldn’t like Metallica or Lacuna Coil.

CF recommenders have a number of advantages. First, they work really well for popular artists. When there are lots of people listening to a set of artists, the overlap is a good indicator of overall preference. Secondly, CF systems are fairly easy to implement. The math is pretty straight forward and conceptually they are very easy to understand. Of course, the devil is in the details. Scaling a CF system to work with millions of artists and billions of tracks for millions of users is an engineering challenge. Still, it is no surprise that CF systems are so widely used. They give good recommendations for popular items and they are easy to understand and implement. However, there are some flaws in CF systems that ultimately makes them not suitable for long-tail music recommendation. Let’s take a look at some of the issues.

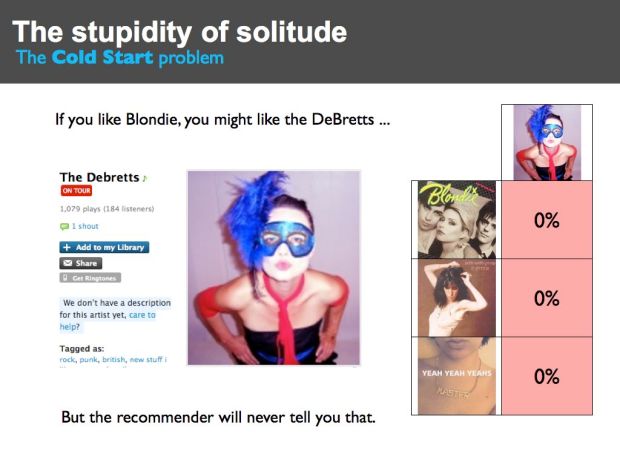

The Stupidity of Solitude

The DeBretts are a long tail artist. They are a punk band with a strong female vocalist that is reminiscent of Blondie or Patti Smith. (Be sure to listen to their song ‘The Rage’) .The DeBretts haven’t made it big yet. At last.fm they have about 200 listeners. They are a really good band and deserve to be heard. But if you went to an online music store like iTunes that uses a Collaborative Filterer to recommend music, you would *never* get a recommendation for the DeBretts. The reason is pretty obvious. The DeBretts may appeal to listeners that like Blondie, but even if all of the DeBretts listeners listen to Blondie the percentage of Blondie listeners that listen to the DeBretts is just too low. If Blondie has a million listeners then the maximum potential overlap(200/1,000,000) is way too small to drive any recommendations from Blondie to the DeBretts. The bottom line is that if you like Blondie, even though the DeBretts may be a perfect recommendation for you, you will never get this recommendation. CF systems rely on the wisdom of the crowds, but for the DeBretts, there is no crowd and without the crowd there is no wisdom. Among those that build recommender systems, this issue is called ‘the cold start’ problem. It is one of the biggest problems for CF recommenders. A CF-based recommender cannot make good recommendations for new and unpopular items.

Clearly we can see that this cold start problem is going to make it difficult for us to find new music in the long tail. The cold start problem is one of the main reasons why are recommenders are still’ stuck in the head’.

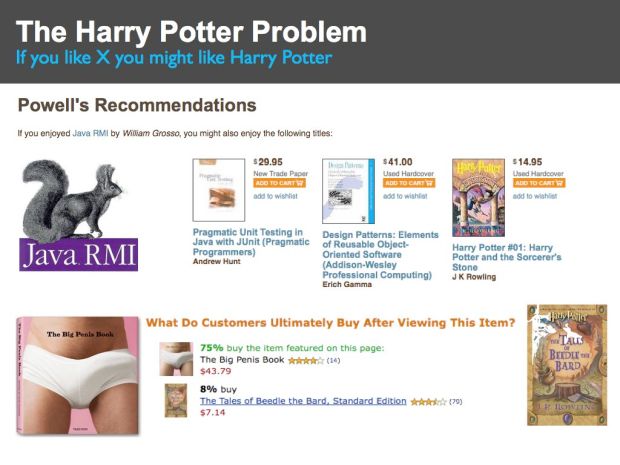

The Harry Potter Problem

This slide shows a recommendation “If you enjoy Java RMI” you many enjoy Harry Potter and the Sorcerers Stone”. Why is Harry Potter being recommended for a reader of a highly technical programming book?

Certain items, like the Harry Potter series of books, are very popular. This popularity can have an adverse affect on CF recommenders. Since popular items are purchased often they are frequently purchased with unrelated items. This can cause the recommender to associate the popular item with the unrelated item, as we see in this case. This effect is often called the Harry Potter effect. People who bought just about any book that you can think of, also bought a Harry Potter book.

Case in point is the “The Big Penis Book” – Amazon tells us that after viewing “The Big Penis Book” 8% of customers go on to by the Tales of Beedle the Bard from the Harry Potter series. It may be true that people who like big penises also like Harry Potter but it may not be the best recommendation.

(BTW, I often use examples from Amazon to highlight issues with recommendation. This doesn’t mean that Amazon has a bad recommender – in fact I think they have one of the best recommenders in the world. Whenever I go to Amazon to buy one book, I end up buying five because of their recommender. The issues that I show are not unique to the Amazon recommender. You’ll find the same issues with any other CF-based recommender.)

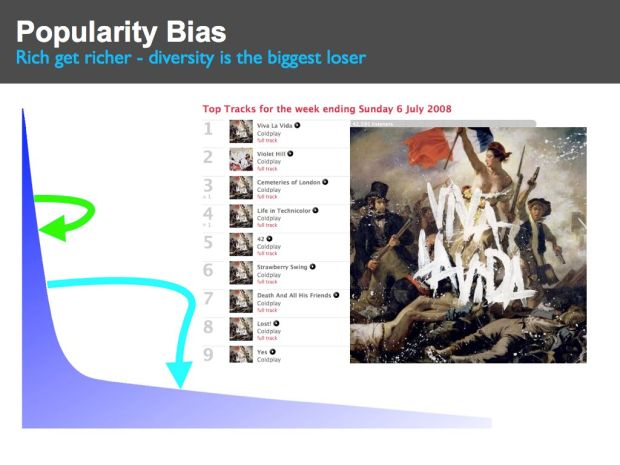

Popularity Bias

One effect of this Harry Potter problem is that a recommender will associate the popular item with many other items. The result is that the popular item tends to get recommended quite often and since it is recommended often, it is purchased often. This leads to a feedback loop where popular items get purchased often because they are recommended often and are recommended often because they are purchased often. This ‘rich-get-richer’ feedback loop leads to a system where popular items become extremely popular at the expense of the unpopular. The overall diversity of recommendations goes down. These feedback loops result in a recommender that pushes people toward more popular items and away from the long tail. This is exactly the opposite of what we are hoping that our recommenders will do. Instead of helping us find new and interesting music in the long tail, recommenders are pushing us back to the same set of very popular artists.

Note that you don’t need to have a fancy recommender system to be susceptible to these feedback loops. Even simple charts such as we see at music sites like the hype machine can lead to these feedback loops. People listen to tracks that are on the top of the charts, leading these songs to continue to be popular, and thus cementing their hold on the top spots in the charts.

The Novelty Problem

There is a difference between a recommender that is designed for music discovery and one that is designed for music shopping. Most recommenders are intended to help a store make more money by selling you more things. This tends to lead to recommendations such as this one from Amazon – that suggests that since I’m interested in Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band that I might like Abbey Road and Please Please Me and every other Beatles album. Of course everyone in the world already knows about these items so these recommendations are not going to help people find new music. But that’s not the point, Amazon wants to sell more albums and recommending Beatles albums is a great way to do that.

One factor that is contributing to the Novelty Problem is high stakes evaluations like the Netflix prize. The Netflix prize is a competition that offers a million dollars to anyone that can improve the Netflix movie recommender by 10%. The evaluation is based on how well a recommender can predict how a movie viewer will rate a movie on a 1-5 star scale. This type of evaluation focuses on relevance – a recommender that can correctly predict that I’ll rate the movie ‘Titanic’ 2.2 stars instead of 2.0 stars – may score well in this type of evaluation, but that probably hasn’t really improved the quality of the recommendation. I won’t watch a 2.0 or a 2.2 star movie, so what does it matter. The downside of the Netflix prize is that only one metric – relevance – is being used to drive the advancement of recommender state-of-the-art when there are other equally import metrics – novelty is one of them.

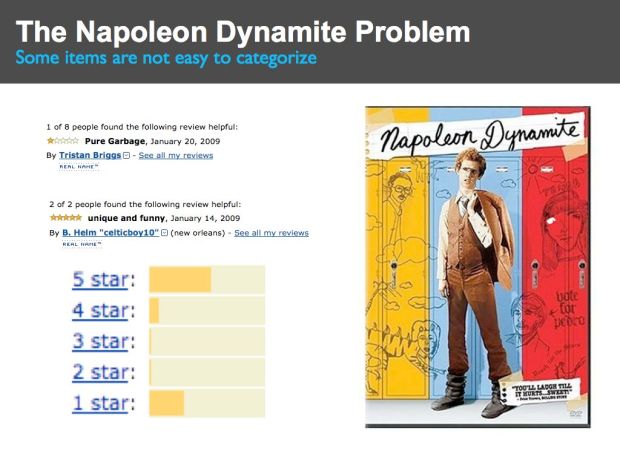

The Napoleon Dynamite Problem

Some items are not always so easy to categorize. For instance, if you look at the ratings for the movie Napoleon Dynamite you see a bimodal distribution of 5 stars and 1 stars. People either like it or hate it, and it is hard to predict how an individual will react.

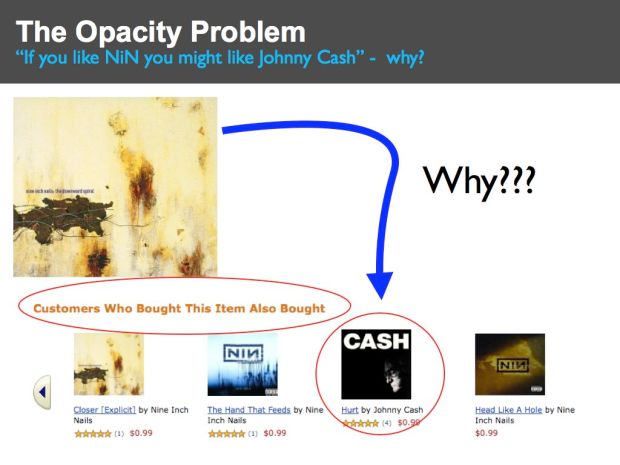

The Opacity Problem

Here’s an Amazon recommendation that suggests that if I like Nine Inch Nails that I might like Johnny Cash. Since NiN is an industrial band and Johnny Cash is a country/western singer, at first blush this seems like a bad recommendation, and if you didn’t know any better you may write this off as just another broken recommender. It would be really helpful if the CF recommender could explain why it is recommending Johnny Cash, but all it can really tell you is that ‘Other people who listened to NiN also listened to Johnny Cash’ which isn’t very helpful. If the recommender could give you a better explanation of why it was recommending something – perhaps something like “Johnny Cash has an absolutely stunning cover of the NiN song ‘hurt’ that will make you cry.” – then you would have a much better understanding of the recommendation. The explanation would turn what seems like a very bad recommendation into a phenomenal one – one that perhaps introduces you to whole new genre of music – a recommendation that may have you listening ‘Folsom Prison’ in a few weeks.

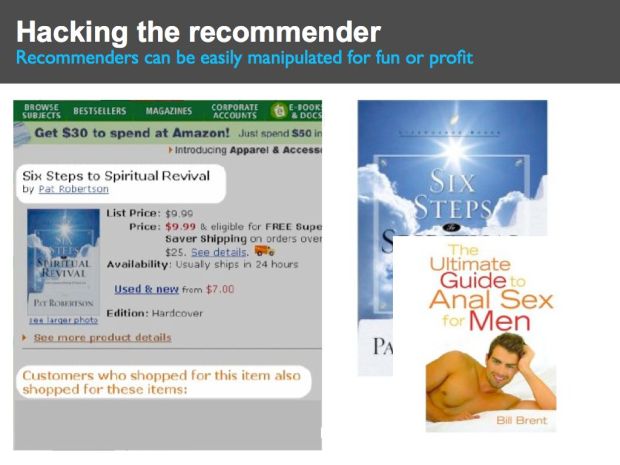

Hacking the Recommender

Here’s a recommendation based on a book by Pat Robertson called Six Steps to Spiritual Revival (courtesy of Bamshad Mobasher). This is a book by notorious televangelist Pat Roberston that promises to reveal “Gods’s Awesome Power in your life.” Amazon offers a recommendation suggesting that ‘Customers who shopped for this item also shopped for ‘The Ultimate Guide to Anal Sex for Men’. Clearly this is not a good recommendation. This bad recommendation is the result of a loosely organized group who didn’t like Pat Roberston, so they managed to trick the Amazon recommender into recommending a rather inappropriate book just by visiting the Amazon page for Robertson’s book and then visiting the Amazon page for the sex guide.

This manipulation of the Amazon recommender was easy to spot and can be classified as a prank, but it is not hard to image that an artist or a label may use similar techniques, but in a more subtle fashion to manipulate a recommender to promote their tracks (or to demote the competition). We already live in a world where search engine optimization is an industry. It won’t be long before recommender engine optimization will be an equally profitable (and destructive) industry.

Wrapping up

This is the first part of a two part post. In this post I’ve highlighted some of the issues in traditional music recommendation. Next post is all about how to fix these problems. For an alternative view be sure to visit Anthony Volodkin’s blog where he presents a rather different viewpoint about music recommendation.

Last.fm and the iPhone

Here’s a nifty iPhone commercial that highlights Last.fm that has been running in the UK. Cool stuff, nicely done Toby!

Twisten.fm – Music gone viral.

Posted by Paul in Music, recommendation on February 13, 2009

The fine folks over at Grooveshark have just released Twisten.fm. Like Blip.fm, Twisten.fm combines micro-blogging and music, and like Blip.fm, instead of creating an entirely new microblogging network, Twisten.fm piggybacks on top of the existing Twitter network.

The fine folks over at Grooveshark have just released Twisten.fm. Like Blip.fm, Twisten.fm combines micro-blogging and music, and like Blip.fm, instead of creating an entirely new microblogging network, Twisten.fm piggybacks on top of the existing Twitter network.

With twisten, you can make tweets with just about any song in the world (Grooveshark has millions of tracks in its catalog) – twisten will automatically generate a twisten tiny url to the song, and if any of your twitter followers click on the link, they are taken directly to the song page on Grooveshark where they can listen to the song.

twisten a song

Here’s what the song tweet looks like on twitter:

Twisten makes it easy for you to tell your twitter followers that you like a song – with Twisten, you just type the name of the song, and twisten does all of the hard work of finding the song in the catalog, generating a tiny URL for the song and posting it to Twitter.

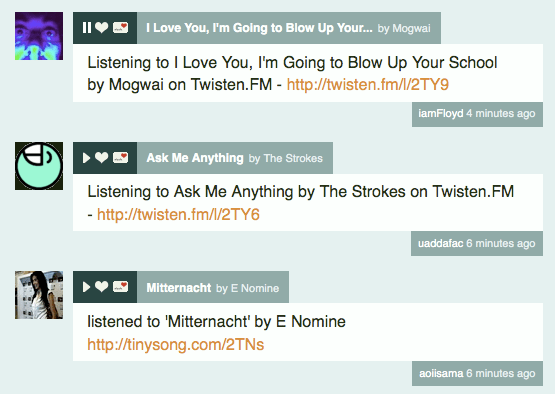

Twisten also makes it easy to listen to music posted by others. If you use the Twisten web app, you can easily listen and browse all of the twisten tweets of your followees or the world at large.

Listening to Twisten tweets

With the twisten app, you just see the Twisten tweets, which makes it a perfect app for browsing through new music. It is easy to listen, since the player is embedded right in the page. You can also listen to the music that is being posted by everyone.

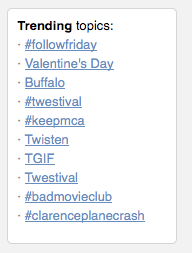

I suspect that Twisten.fm is going to be a really big deal. First and foremost, it is an incredibly viral app. Just by using Twisten, you are telling all the world about it. 18 hours after it’s release, Twisten is #6 on the list of Twitter trending topics.

Second, it doesn’t re-invent the wheel. Instead of building a whole new social network, it sits on top of Twitter, one of the largest existing social networks – it doesn’t have to build up a network from scratch.

Second, it doesn’t re-invent the wheel. Instead of building a whole new social network, it sits on top of Twitter, one of the largest existing social networks – it doesn’t have to build up a network from scratch.

Twisten is really neat, I like it a lot – still, there are a few places where it could be improved.

First of all, when listening to music on the Twisten site, the music should never stop when I navigate to a different part of the site. Right now, if I’m listening to a particular tweet, and decide to check out what ‘everybody is listening to’, the music stops. The main Grooveshark app does a much better job of keeping the music playing all the time whilst one navigates through the site.

Currently, when I click on a twisten tiny url in twitter to listen to a song, instead of taking me to Twisten, the URL takes me to Grooveshark. I understand that Grooveshark is hosting all of the music, but it seems to me that if you want to really make Twisten go viral, the links should bring listeners straight to Twisten, where they can listen to the music, and while there, start Twisten their own tweets.

The listening experience on Twisten is a hunt-and-peck style. I see a song, I click on it, I listening to it, and then I go and find the next song. That’s fine when I am exploring for new music, but if I just want to listen to music, I’d like to be able to turn Twisten into a radio station, where I listen to the music that my friends have been twittering. Ideally, I should be able to listen to tweets all day without having to click a mouse button. TheSixtyOne does a great job of keeping the music flowing. Twisten should follow their model.

I wish Twisten.fm would scrobble all my tweets and listens – it’d be great if every music app in the world scrobbled my listening behavior.

Twisten is able to collect all sorts of interesting information about who is listening to what music. I hope they do some interesting things with this data. For instance, they could create a Twitter Music Zeitgest that shows the songs and artists that are rising, popular, or falling. Since Twisten knows what I’ve been listening to, and what I like (because I can ‘favorite’ twisten songs), Twisten should be able to connect me up with other Twisten listeners that have similar tastes so I can use their twitters and listens to guide my own listening. Twisten is going to be able to collect lots and lots of user listener data, so it should be interesting to see what they do with it all.

Twisten has the potential to be the real breakout music application of 2009. It has all the ingredients – a huge catalog of free music, and a viral model that leverages one of the largest and most active social networks. When iLike released it’s facebook app, iLike became the fastest growing music app ever, adding 3 million users in two weeks. Twisten has a good chance to do the same thing.