ISMIR Session – the web

The first session at ISMIR today is on the Web. 4 really interesting sets of papers:

Songle – an active music listening experience

Mastaka Goto presented Songle at ISMIR this morning. Songle is a web site for active music listening and content-based music browsing. Songle takes many of the MIR techniques that researchers have been working on for years and makes it available to non-MIR experts to help them understand music better. You can also use Songle to modify the music. You can interactively change the beat and melody, copy and paste sections. Your edits can be shared with others. Masataka hopes that Songle can serve as a showcase of MIR and music-understanding of technologies and will serve as a platform for other researchers as well. There’s a lot of really powerful music technology behind Songle. I look forward to trying it out. Paper.

Improving Perceptual Tempo estimation with Crowd-Source Annotations

Mark Levy from Last.fm describes the Last.fm experiment to crowd source the gathering of tempo information (fast, slow and BPM) that can be used to help eliminate tempo ambiguity in machine-estimated tempo (typically known as the octave error). They ran their test over 4K songs from a number of genres. So far they’ve had 27K listeners apply 200k labels and bpm estimates. (woah!). Last.fm is releasing this dataset. Very interesting work. Paper

Investigating the similarity space of music artists on the micro-blogosphere

Markus Schedl analyzed 6 million tweets by searching tweets for artist names and conducted a number of experiments to see if artist similarity could be determined based upon these tweets. (They used the Comirva framework to conduct the experiments). Findings: document based techniques work best (cosine similarity, while not always yielding the best result yielded the most stable results). Unsurprisingly adding the term ‘music’ to the twitter search helps a lot (Reducing the CAKE, Spoon and KISS problems). Surprising result is that using tweets for deriving similarity works better than using larger documents derived from web search. Markus suggest that this may be due to the higher information content in the much shorter tweets. Datasets are available. Paper

Music Influence Network Analysis and Rank of Sample-based Music

Nick Bryan from Stanford – trying to understand how songs/artists and genres interact with the sampled-base music (remixes etc). Using data from Whosampled.com – (42K user-generated sample info sets). From this data they created an directed graph and did some network analysis on the graph (centrality / influence) – Hypothesized that there’s a power law distribution of connectivity (typical small-worlds, scale-free distribution with a rich-gets-richer effect). They confirmed this hypothesis. Use Katz Influence to help understand sample-chains. From the song-sample graph, artist sample graphs (who sampled whom) and genre sample graphs (which genres sample from other genres) were derived. With all these graphs, Nick was then able to understand which songs and artists are the most influential (James Brown is king of sampling), surprisingly, the AMEN break is only the second most influential sample. Interesting and fun work. Paper

Music Recommendation and Discovery Remastered – A Tutorial

Posted by Paul in events, Music, recommendation on October 24, 2011

Oscar and I just finished giving our tutorial on music recommendation and discovery at ACM RecSys 2011. Here are the slides:

What is so special about music?

Posted by Paul in Music, recommendation on October 23, 2011

In the Recommender Systems world there is a school of thought that says that it doesn’t matter what type of items you are recommending. For these folks, a recommender is a black box that takes in user behavior data and outputs recommendations. It doesn’t matter what you are recommending – books, music, movies, Disney vacations, or deodorant. According to this school of thought you can take the system that you use for recommending books and easily repurpose it to recommend music. This is wrong. If you try to build a recommender by taking your collaborative filtering book recommender and applying it to music, you will fail. Music is different. Music is special.

Here are 10 reasons why music is special and why your off-the-shelf collaborative filtering system won’t work so well with music.

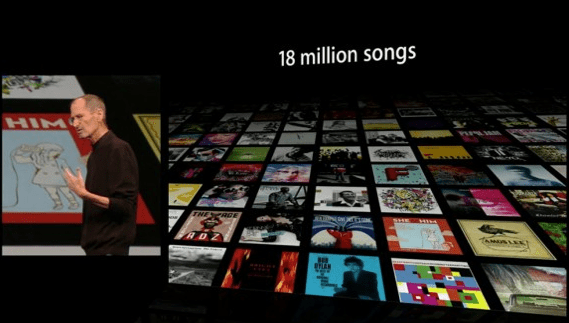

Huge item space – There is a whole lot of music out there. Industrial sized music collections typically have 10 million songs or more. The iTunes music store boasts 18 million songs. The algorithms that worked so wonderfully on the Netfix Dataset (one of the largest CF datasets released, contain user data for 17,770 movies) will not work so well when having to deal with a dataset that is three orders of magnitude larger.

Very low cost per item – When the cost per item is low, the risk of a bad recommendation is low. If you recommend to me a bad Disney Vacation I am out $10,000 and a week of my time. If you recommend a bad song, I hit the skip button and move on to the next.

Many item types – In the music world, there are many things to recommend: tracks, albums, artists, genres, covers, remixes, concerts, labels, playlists, radio stations other listeners etc.

Low consumption time – A book can take a week to read, a movie may take a few hours to watch, a song may take 3 minutes to listen to. Since I can consume music so quickly, I need lots of recommendations (perhaps 30 an hour) to keep my queue filled, whereas 30 book recommendations may keep me reading for a whole year. This has implications for scaling of a recommender. It also ties in with the low cost per item issue. Because music is so cheap and so quick to consume, the risk of a bad recommendation is very low. A music recommender can afford to be more adventurous than other types of recommenders.

Very high per-item reuse – I’ve read my favorite book perhaps half-a-dozen times, I’ve seen my favorite movie 3 times and I’ve probably listened to my favorite song thousands of times. We listen to music over and over again. We like familiar music. A music recommender has to understand the tension between familiarity and novelty. The Netflix movie recommender will never recommend The Bourne Identity to me because it knows that I already watched it, but a good music playlist recommender had better include a good mix of my old favorites along with new music.

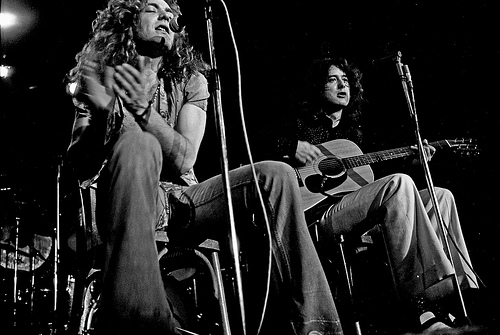

Highly passionate users -There’s no more passionate fan than a music fan. This is a two-edged sword. If your recommender introduce a music fan to new music that they like they will transfer some of their passion to your music service. This is why Pandora has such a vocal and passionate user base. On the other hand, if your recommender adds a Nickelback track to a Led Zeppelin playlist you will have to endure the wrath of the slighted fan.

Highly contextual usage – We listen to music differently in different contexts. I may have an exercising playlist, a working playlist, a driving playlist etc. I may make a playlist to show my friends how cool I am when I have them over for a social gathering. Not too many people go to Amazon looking for a list of books that they can read while jogging. A successful music recommender needs to take context into account.

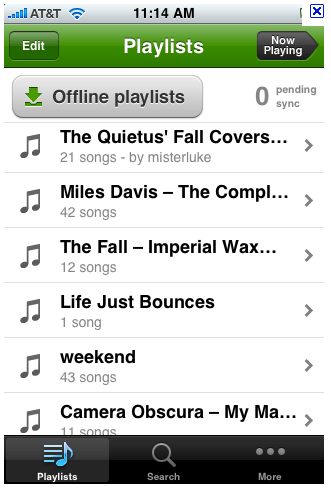

Consumed in sequences – Listening to songs in order has always been a big part of the music experience. We love playlists, mixtapes, DJ mixes, albums. Some people make their living putting songs into interesting order. Your collaborative filtering algorithm doesn’t have the ability to create coherent, interesting playlists with a mix of new music and old favorites

Large Personal Collections – Music fans often have extremely large personal collections – making it easier for recommendation and discovery tools to understand the detailed music taste of a listener. A personalized movie recommender may start with a list of a dozen rated movies, while a music recommender may be able to recommend music based upon many thousands of plays, ratings skips and bans.

Highly Social – Music is social. People love to share music. They express their identity to others by the music they listen to. They give each other playlists and mixtapes. Music is a big part of who we are.

Music is special – but of course, so are books, movies and Disney vacations – every type of item has its own special characteristics that should be taken into account when building recommendation and discovery tools. There’s no one-size-fits-all recommendation algorithm.

“What do I do with those 10,000,000 songs in my pocket?”

References to Mae West aside, I’m really looking forward to the Industrial Panel being held during the Workshop on Music Recommendation and Discovery. Great set of attendees:

- Amélie Anglade (Soundcloud, GE) moderator

- Eric Bieschke (Pandora, US)

- Douglas Eck (Google Music, US)

- Justin Sinkovich (Epitonic, US)

- Evan Stein (Decibel, UK)

Music Recommendation and Discovery Revisited

Posted by Paul in freakomendation, recommendation on October 22, 2011

I’m off to Chicago to attend the 5th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems. I’m giving a talk with Òscar Celma called Music Recommendation and Discovery Revisited. It is a reprise of the talk we gave 4 years ago at ISMIR 2007 in Austria. Quite a bit has happened in the music discovery space since then so there’s quite a bit of new material. Here’s one of my favorite new slides. 10 points if you can figure out what this slide is all about.

It should be a fun talk, and it is always great working with Oscar. We’ll post the slides on Monday.

Search for music by drawing a picture of it

I’ve spent the weekend hacking on a project at Music Hack Day Montreal. For my hack I created an application with the catchy title “Search for music by drawing a picture of it”. The hack lets you draw the loudness profile for a song and the app will search through the Million Song Data Set to find the closest match. You can then listen to the song in Spotify (if the song is in the Spotify collection).

Coding a project in 24 hours is all about compromise. I had some ideas that I wanted to explore to make the matching better (dynamic time warping) and the lookup faster (LSH). But since I actually wanted to finish my hack I’ve saved those improvements for another day. The simple matching approach (Euclidean distance between normalized vectors) works surprisingly well. The linear search through a million loudness vectors takes about 20 seconds, too long for a web app, this can be made palatable with a little Ajax .

The hack day has been great fun, kudos to the Montreal team for putting it all together.

Looking for the Slow Build

This is the second in a series of posts exploring the Million Song Dataset.

Every few months you’ll see a query like this on Reddit – someone is looking for songs that slowly build in intensity. It’s an interesting music query since it is primarily focused on what the music sounds like. Since we’ve analyzed the audio of millions and millions of tracks here at The Echo Nest we should be able to automate this type of query. One would expect that Slow Build songs will have a steady increase in volume over the course of a song, so lets look at the loudness data for a few Slow Build songs to confirm this intuition. First, here’s the canonical slow builder: Stairway to Heaven:

The green line is the raw loudness data, the blue line is a smoothed version of the data. Clearly we see a rise in the volume over the course of the song. Let’s look at another classic Slow Build – The Hall Of the Mountain King – again our intuition is confirmed:

The green line is the raw loudness data, the blue line is a smoothed version of the data. Clearly we see a rise in the volume over the course of the song. Let’s look at another classic Slow Build – The Hall Of the Mountain King – again our intuition is confirmed:

Looking at a non-Slow Build song like Katy Perry’s California Gurls we see that the loudness curve is quite flat by comparison:

Of course there are other aspects beyond loudness that a musician may use to build a song to a climax – tempo, timbre and harmony are all useful, but to keep things simple I’m going to focus only on loudness.

Looking at these plots it is easy to see which songs have a Slow Build. To algorithmically identify songs that have a slow build, we can use a technique similar to the one I described in The Stairway Detector. It is a simple algorithm that compares the average loudness of the first half of the song to the average loudness of the second half of the song. Songs with the biggest increase in average loudness rank the highest. For example, take a look at a loudness plot for Stairway to Heaven. You can see that there is a distinct rise in scores from the first half to the second half of the song (the horizontal dashed lines show the average loudness for the first and second half of the song). Calculating the ramp factor we see that Stairway to Heaven scores an 11.36 meaning that there is an increase in average loudness of 11.36 decibels between the first and the second half of the song.

This algorithm has some flaws – for instance it will give very high scores to ‘hidden track’ songs. Artists will sometimes ‘hide’ a track at the end of a CD by padding the beginning of the track with a few minutes of silence. For example, this track by ‘Fudge Tunnel’ has about five minutes of silence before the band comes in.

Clearly this song isn’t a Slow Build, our simple algorithm is fooled. To fix this we need to introduce a measure of how straight the ramp is. One way to measure the straightness of a line is to calculate the Pearson correlation for the loudness data as a function of time. XY Data with correlation that approaches one (or negative one) is by definition, linear. This nifty wikipedia visualization of the correlation of different datasets shows the correlation for various datasets:

We can combine the correlation with our ramp factors to generate an overall score that takes into account the ramp of the song as well as the straightness of the ramp. The overall score serves as our Slow Build detector. Songs with a high score are Slow Build songs. I suspect that there are better algorithms for this so if you are a math-oriented reader who is cringing at my naivete please set me and my algorithm straight.

We can combine the correlation with our ramp factors to generate an overall score that takes into account the ramp of the song as well as the straightness of the ramp. The overall score serves as our Slow Build detector. Songs with a high score are Slow Build songs. I suspect that there are better algorithms for this so if you are a math-oriented reader who is cringing at my naivete please set me and my algorithm straight.

Armed with our Slow Build Detector, I built a little web app that lets you explore for Slow Build songs. The app – Looking For The Slow Build – looks like this:

The application lets you type in the name of your favorite song and will give you a plot of the loudness over the course of the song, and calculates the overall Slow Build score along with the ramp and correlation. If you find a song with an exceptionally high Slow Build score it will be added to the gallery. I challenge you to get at least one song in the gallery.

You may find that some songs that you think should get a high Slow Build score don’t score as high as you would expect. For instance, take the song Hoppipolla by Sigur Ros. It seems to have a good build, but it scores low:

It has an early build but after a minute it has reached it’s zenith. The ending is symmetrical with the beginning with a minute of fade. This explains the low score.

Another song that builds but has a low score is Weezer’s The Angel and the One.

This song has a 4 minute power ballad build – but fails to qualify a a slow build because the last 2 minutes of the song are nearly silent.

Finding Slow Build songs in the Million Song Dataset

Now that we have an algorithm that finds Slow Build songs, lets apply it to the Million Song Dataset. I can create a simple MapReduce job in Python that will go through all of the million tracks and calculate the Slow Build score for each of them to help us find the songs with the biggest Slow Build. I’m using the same framework that I described in the post “How to Process a Million Songs in 20 minutes“. I use the S3 hosted version of the Million Song Dataset and process it via Amazon’s Elastic MapReduce using mrjob – a Python MapReduce library. Here’s the mapper that does almost all of the work, the full code is on github in cramp.py:

def mapper(self, _, line):

""" The mapper loads a track and yields its ramp factor """

t = track.load_track(line)

if t and t['duration'] > 60 and len(t['segments']) > 20:

segments = t['segments']

half_track = t['duration'] / 2

first_half = 0

second_half = 0

first_count = 0

second_count = 0

xdata = []

ydata = []

for i in xrange(len(segments)):

seg = segments[i]

seg_loudness = seg['loudness_max'] * seg['duration']

if seg['start'] + seg['duration'] <= half_track:

seg_loudness = seg['loudness_max'] * seg['duration']

first_half += seg_loudness

first_count += 1

elif seg['start'] < half_track and seg['start'] + seg['duration'] > half_track:

# this is the nasty segment that spans the song midpoint.

# apportion the loudness appropriately

first_seg_loudness = seg['loudness_max'] * (half_track - seg['start'])

first_half += first_seg_loudness

first_count += 1

second_seg_loudness = seg['loudness_max'] * (seg['duration'] - (half_track - seg['start']))

second_half += second_seg_loudness

second_count += 1

else:

seg_loudness = seg['loudness_max'] * seg['duration']

second_half += seg_loudness

second_count += 1

xdata.append( seg['start'] )

ydata.append( seg['loudness_max'] )

correlation = pearsonr(xdata, ydata)

ramp_factor = second_half / half_track - first_half / half_track

if YIELD_ALL or ramp_factor > 10 and correlation > .5:

yield (t['artist_name'], t['title'], t['track_id'], correlation), ramp_factor

This code takes less than a half hour to run on 50 small EC2 instances and finds a bucketload of Slow Build songs. I’ve created a page of plots of the top 500 or so Slow Build songs found by this job. There are all sorts of hidden gems in there. Go check it out:

Looking for the Slow Build in the Million Song Dataset

The page has 500 plots all linked to Spotify so you can listen to any song that strikes your fancy. Here are some my favorite discoveries:

Respighi’s The Pines of the Appian Way

I remember playing this in the orchestra back in high school. It really is sublime. Click the plot to listen in Spotify.

Maria Friedman’s Play The Song Again

So very theatrical

Mandy Patinkin’s Rock-A-Bye Your Baby With A Dixie Melody

Another song that seems to be right off of Broadway – it has an awesome slow build.

- The Million Song Dataset – deep data about a million songs

- The Stairway Index – my first look at this stuff about 2 years ago

- How to process a million songs in 20 minutes – a blog post about how to process the MSD with mrjob and Elastic Map Reduce

- Looking for the Slow Build – a simple web app that calculates the Slow Build score and loudness plot for just about any song

- cramp.py – the MapReduce code for calculating Slow Build scores for the MSD

- Looking for the Slow Build in the Million Song Dataset – 500 loudness plots of the top Slow Builders

- Top Slow Build songs in the Million Song Dataset – the top 6K songs with a Slow Build score of 10 and above

- A Spotify collaborative playlist with a bunch of Slow Build songs in it. Feel free to add more.

How to process a million songs in 20 minutes

The recently released Million Song Dataset (MSD), a collaborative project between The Echo Nest and Columbia’s LabROSA is a fantastic resource for music researchers. It contains detailed acoustic and contextual data for a million songs. However, getting started with the dataset can be a bit daunting. First of all, the dataset is huge (around 300 gb) which is more than most people want to download. Second, it is such a big dataset that processing it in a traditional fashion, one track at a time, is going to take a long time. Even if you can process a track in 100 milliseconds, it is still going to take over a day to process all of the tracks in the dataset. Luckily there are some techniques such as Map/Reduce that make processing big data scalable over multiple CPUs. In this post I shall describe how we can use Amazon’s Elastic Map Reduce to easily process the million song dataset.

The Problem

For this first experiment in processing the million song data set I want to do something fairly simple and yet still interesting. One easy calculation is to determine each song’s density – where the density is defined as the average number of notes or atomic sounds (called segments) per second in a song. To calculate the density we just divide the number of segments in a song by the song’s duration. The set of segments for a track is already calculated in the MSD. An onset detector is used to identify atomic units of sound such as individual notes, chords, drum sounds, etc. Each segment represents a rich and complex and usually short polyphonic sound. In the above graph the audio signal (in blue) is divided into about 18 segments (marked by the red lines). The resulting segments vary in duration. We should expect that high density songs will have lots of activity (as an Emperor once said “too many notes”), while low density songs won’t have very much going on. For this experiment I’ll calculate the density of all 1 million songs and find the most dense and the least dense songs.

MapReduce

A traditional approach to processing a set of tracks would be to iterate through each track, process the track, and report the result. This approach, although simple, will not scale very well as the number of tracks or the complexity of the per track calculation increases. Luckily, a number of scalable programming models have emerged in the last decade to make tackling this type of problem more tractable. One such approach is MapReduce.

MapReduce is a programming model developed by researchers at Google for processing and generating large data sets. With MapReduce you specify a map function that processes a key/value pair to generate a set of intermediate key/value pairs, and a reduce function that merges all intermediate values associated with the same intermediate key. There are a number of implementations of MapReduce including the popular open sourced Hadoop and Amazon’s Elastic MapReduce.

There’s a nifty MapReduce Python library developed by the folks at Yelp called mrjob. With mrjob you can write a MapReduce task in Python and run it as a standalone app while you test and debug it. When your mrjob is ready, you can then launch it on a Hadoop cluster (if you have one), or run the job on 10s or even 100s of CPUs using Amazon’s Elastic MapReduce. Writing an mrjob MapReduce task couldn’t be easier. Here’s the classic word counter example written with mrjob:

from mrjob.job import MRJob

class MRWordCounter(MRJob):

def mapper(self, key, line):

for word in line.split():

yield word, 1

def reducer(self, word, occurrences):

yield word, sum(occurrences)

if __name__ == '__main__':

MRWordCounter.run()

The input is presented to the mapper function, one line at a time. The mapper breaks the line into a set of words and emits a word count of 1 for each word that it finds. The reducer is called with a list of the emitted counts for each word, it sums up the counts and emits them.

When you run your job in standalone mode, it runs in a single thread, but when you run it on Hadoop or Amazon (which you can do by adding a few command-line switches), the job is spread out over all of the available CPUs.

MapReduce job to calculate density

We can calculate the density of each track with this very simple mrjob – in fact, we don’t even need a reducer step:

class MRDensity(MRJob):

""" A map-reduce job that calculates the density """

def mapper(self, _, line):

""" The mapper loads a track and yields its density """

t = track.load_track(line)

if t:

if t['tempo'] > 0:

density = len(t['segments']) / t['duration']

yield (t['artist_name'], t['title'], t['song_id']), density

(see the full code on github)

The mapper loads a line and parses it into a track dictionary (more on this in a bit), and if we have a good track that has a tempo then we calculate the density by dividing the number of segments by the song’s duration.

Parsing the Million Song Dataset

We want to be able to process the MSD with code running on Amazon’s Elastic MapReduce. Since the easiest way to get data to Elastic MapReduce is via Amazon’s Simple Storage Service (S3), we’ve loaded the entire MSD into a single S3 bucket at http://tbmmsd.s3.amazonaws.com/. (The ‘tbm’ stands for Thierry Bertin-Mahieux, the man behind the MSD). This bucket contains around 300 files each with data on about 3,000 tracks. Each file is formatted with one track per line following the format described in the MSD field list. You can see a small subset of this data for just 20 tracks in this file on github: tiny.dat. I’ve written track.py that will parse this track data and return a dictionary containing all the data.

You are welcome to use this S3 version of the MSD for your Elastic MapReduce experiments. But note that we are making the S3 bucket containing the MSD available as an experiment. If you run your MapReduce jobs in the “US Standard Region” of Amazon, it should cost us little or no money to make this S3 data available. If you want to download the MSD, please don’t download it from the S3 bucket, instead go to one of the other sources of MSD data such as Infochimps. We’ll keep the S3 MSD data live as long as people don’t abuse it.

Running the Density MapReduce job

You can run the density MapReduce job on a local file to make sure that it works:

% python density.py tiny.dat

This creates output like this:

["Planet P Project", "Pink World", "SOIAZJW12AB01853F1"] 3.3800521773317689 ["Gleave", "Come With Me", "SOKBZHG12A81C21426"] 7.0173630509232234 ["Chokebore", "Popular Modern Themes", "SOGVJUR12A8C13485C"] 2.7012807851495166 ["Casual", "I Didn't Mean To", "SOMZWCG12A8C13C480"] 4.4351713380683542 ["Minni the Moocher", "Rosi_ das M\u00e4dchen aus dem Chat", "SODFMEL12AC4689D8C"] 3.7249476012698159 ["Rated R", "Keepin It Real (Skit)", "SOMJBYD12A6D4F8557"] 4.1905674943168156 ["F.L.Y. (Fast Life Yungstaz)", "Bands", "SOYKDDB12AB017EA7A"] 4.2953929132587785

Where each ‘yield’ from the mapper is represented by a single line in the output, showing the track ID info and the calculated density.

Running on Amazon’s Elastic MapReduce

When you are ready to run the job on a million songs, you can run it the on Elastic Map Reduce. First you will need to set up your AWS system. To get setup for Elastic MapReduce follow these steps:

- create an Amazon Web Services account: <http://aws.amazon.com/>

- sign up for Elastic MapReduce: <http://aws.amazon.com/elasticmapreduce/>

- Get your access and secret keys (go to <http://aws.amazon.com/account/> and click on “Security Credentials”)

- Set the environment variables $AWS_ACCESS_KEY_ID and $AWS_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY accordingly for mrjob.

Once you’ve set things up, you can run your job on Amazon using the entire MSD as input by adding a few command switches like so:

% python density.py --num-ec2-instances 100 --python-archive t.tar.gz -r emr 's3://tbmmsd/*.tsv.*' > out.dat

The ‘-r emr’ says to run the job on Elastic Map Reduce, and the ‘–num-ec2-instances 100’ says to run the job on 100 small EC2 instances. A small instance currently costs about ten cents an hour billed in one hour increments, so this job will cost about $10 to run if it finishes in less than an hour, and in fact this job takes about 20 minutes to run. If you run it on only 10 instances it will cost 1 or 2 dollars. Note that the t.tar.gz file simply contains any supporting python code needed to run the job. In this case it contains the file track.py. See the mrjob docs for all the details on running your job on EC2.

The Results

The output of this job is a million calculated densities, one for each track in the MSD. We can sort this data to find the most and least dense tracks in the dataset. Here are some high density examples:

Ichigo Ichie by Ryuji Takeuchi has a density of 9.2 segments/second

Ichigo Ichie by Ryuji Takeuchi

129 by Strojovna 07 has a density of 9.2 segments/second

129 by Strojovna 07

The Feeding Circle by Makaton with a density of 9.1 segments per segment

The Feeding Circle by Makaton

Indeed, these pass the audio test, they are indeed high density tracks. Now lets look at some of the lowest density tracks.

Deviation by Biosphere with a density of .014 segments per second

Deviation by Biosphere

The Wire IV by Alvin Lucier with a density of 0.014 segments per second

The Wire IV by Alvin Lucier

improvisiation_122904b by Richard Chartier with a density of .02 segments per second

improvisation by Richard Chartier

Wrapping up

The ‘density’ MapReduce task is about as simple a task for processing the MSD that you’ll find. Consider this the ‘hello, world’ of the MSD. Over the next few weeks, I’ll be creating some more complex and hopefully interesting tasks that show some of the really interesting knowledge about music that can be gleaned from the MSD.

(Thanks to Thierry Bertin-Mahieux for his work in creating the MSD and setting up the S3 buckets. Thanks to 7Digital for providing the audio samples)

How do you discover music?

Posted by Paul in Music, recommendation, research on August 18, 2011

I’m interested in learning more about how people are discovering new music. I hope that you will spend 2 mins and take this 3 question poll. I’ll publish the results in a few weeks.