Loudest songs in the world

Posted by Paul in fun, Music, The Echo Nest on August 17, 2011

Lots of ink has been spilled about the Loudness war and how modern recordings keep getting louder as a cheap method of grabbing a listener’s attention. We know that, in general, music is getting louder. But what are the loudest songs? We can use The Echo Nest API to answer this question. Since the Echo Nest has analyzed millions and millions of songs, we can make a simple API query that will return the set of loudest songs known to man. (For the hardcore geeks, here’s the API query that I used). Note that I’ve restricted the results to those in the 7Digital-US catalog in order to guarantee that I’ll have a 30 second preview for each song.

So without further adieu, here are the loudest songs

Topping and Core by Grimalkin555

The song Topping and Core by Grmalking555 has a whopping loudness of 4.428 dB.

Modifications by Micron

The song Modifications by Micron has a loudness of 4.318 dB.

Hey You Fuxxx! by Kylie Minoise

The song Hey You Fuxxx! by Kylie Minoise with a loudness of 4.231 dB

Here’s a little taste of Kylie Minoise live (you may want to turn down your volume)

War Memorial Exit by Noma

The song War Memorial Exit by Noma with a loudness of 4.166 dB

Hello Dirty 10 by Massimo

The song Hello Dirty 10 by Massimo with a loudness of 4.121 dB.

These songs are pretty niche. So I thought it might be interesting to look the loudest songs culled from the most popular songs. Here’s the query to do that. The loudest popular song is:

Welcome to the Jungle by Guns 'N Roses

The loudest popular song is Welcome to the Jungle by Guns ‘N Roses with a loudness of -1.931 dB.

You may be wondering how a loudness value can be greater than 0dB. Loudness is a complex measurement that is both a function of time and frequency. Unlike traditional loudness measures, The Echo Nest analysis models loudness via a human model of listening, instead of directly mapping loudness from the recorded signal. For instance, with a traditional dB model a simple sinusoidal function would be measured as having the same exact “amplitude” (in dB) whether at 3KHz or 12KHz. But with The Echo Nest model, the loudness is lower at 12KHz than it is at 3KHz because you actually perceive those signals differently.

Thanks to the always awesome 7Digital for providing album art and 30 second previews in this post.

25 SXSW Music Panels worth voting for

Posted by Paul in events, Music, The Echo Nest on August 16, 2011

Yesterday, SXSW opened up the 2012 Panel Picker allowing you to vote up (or down) your favorite panels. The SXSW organizers will use the voting info to help whittle the nearly 3,600 proposals down to 500. I took a tour through the list of music related panel proposals and selected a few that I think are worth voting for. Talks in green are on my “can’t miss this talk” list. Note that I work with or have collaborated with many of the speakers on my list, so my list can not be construed as objective in any way.

There are many recurring themes. Turnatable.fm is everywhere. Everyone wants to talk about the role of the curator in this new world of algorithmic music recommendations. And Spotify is not to be found anywhere!

I’ve broken my list down into a few categories:

Social Music – there must be a twenty panels related to social music. (Eleven(!) have something to do with Turntable.fm) My favorites are:

- Social Music Strategies: Viral & the Power of Free – with folks from MOG, Turntable, Sirius XM, Facebook and Fred Wilson. I’m not a big fan of big panels (by the time you get done with the introductions, it is time for Q&A), but this panel seems stacked with people with an interesting perspective on the social music scene. I’m particularly interested in hearing the different perspectives from Turntable vs. Sirius XM.

- Can Social Music Save the Music Industry? – Rdio, Turntable, Gartner, Rootmusic, Songkick – Another good lineup of speakers (Turntable.fm is everywhere at SXSW this year) exploring social music. Curiously, there’s no Spotify here (or as far as I can tell on any talks at SXSW).

- Turntable.fm the Future of Music is Social – Turntable.fm – This is the turntable.fm story.

- Reinventing Tribal Music in the land of Earbuds – AT&T – this talk explores how music consumption changes with new social services and the technical/sociological issues that arise when people are once again free to choose and listen to music together.

Man vs. Machine – what is the role of the human curator in this age of algorithmic recommendation and music. Curiously, there are at least 5 panel proposals on this topic.

- Music Discovery:Man Vs. Machine – MOG, KCRW, Turntable.fm, Heather Browne

- Music/Radio Content: Tastemakers vs. Automation – Slacker

- Editor vs. Algorithm in the Music Discovery Space – SPIN, Hype Machine, Echo Nest, 7Digital

- Curation in the age of mechanical recommendations – Matt Ogle / Echo Nest – This is my pick for the Man vs. Machine talk. Matt is *the* man when it comes to understanding what is going on in the world of music listening experience.

- Crowding out the Experts – Social Taste Formation – Last.fm, Via, Rolling Stone – Is social media reducing the importance of reviewers and traditional cultural gatekeepers? Are Yelp, Twitter, Last.fm and other platforms creating a new class of tastemakers?

Music Discovery – A half dozen panels on music recommendation and discovery. Favs include:

- YouKnowYouWantIt: Recommendation Engines that Rock – Netflix, Pandora, Match.com – this panel is filled with recommendation rock stars

- The Dark Art of Digital Music Recommendations – Rovi – Michael Papish of Rovi promises to dive under the hood of music recommendation.

- No Points for Style: Genre vs. Music Networks – SceneMachine – Any talk proposal with statements like “Genre uses a 19th-century tool — a Darwinian tree — to solve a 21st-century problem. And unlike evolutionary science, it’s subjective. By the time a genre branch has been labeled (viz. “grunge”), the scene it describes is as dead as Australopithecus.” is worth checking out.

Mobile Music – Is that a million songs in your pocket or are you just glad to see me?

- Music Everywhere: Are we there yet? – Soundcloud, Songkick, Jawbone – Have we arrived at the proverbial celestial jukebox? What are the challenges?

Big Data – exploring big data sets to learn about music

- Data Mining Music – Paul Lamere – Shameless self promotion. What can we learn if we have really deep data about millions of songs?

- The Wisdom of Thieves: Meaning in P2P Behavior – Ben Fields – Don’t miss Ben’s talk about what we can learn about music (and other media) from mining P2P behavior. This talk is on my must see list.

- Big data for Everyman: Help liberate the data serf – Splunk – webifying and exploiting big data

Echo Nesty panels – proposals from folks from the nest. Of course, I recommend all of these fine talks.

- Active Listening – Tristan Jehan – Tristan takes a look at how the music experience is changing now that the listener can take much more active control of the listening experience. There’s no one who understands music analysis and understanding better than Tristan.

- Data Mining Music – Paul Lamere – This is my awesome talk about extracting info from big data sets like the Million Song Dataset. If you are a regular reader of this blog, you’ll know that I’ll be looking at things like click track detectors, passion indexes, loudness wars and son on.

- What’s a music fan worth? – Jim Lucchese – Echo Nest CEO takes a look at the economics of music, from iOS apps to musicians. Jim knows this stuff better than anyone.

- Music Apps Gone Wild – Eliot Van Buskirk – Eliot takes a tour of the most advanced, wackiest music apps that exist — or are on their way to existing.

- Curation in the age of mechanical recommendations – Matt Ogle – Matt is a phenomenal speaker and thinker in the music space. His take on the role of the curator in this world of algorithms is at the top of my SXSW panel list.

- Editor vs. Algorithm in the Music Discovery Space – SPIN, Hype Machine, Echo Nest (Jim Lucchese), 7Digital

- Defining Music Discovery through Listening – Echo Nest (Tristan Jehan), Hunted Media – This session will examine “true” music discovery through listening and how technology is the facilitator.

Miscellaneous topics

- Designing Future Music Experiences – Rdio, Turntable, Mary Fagot – A look at the user experience for next generation music apps.

- Music at the App Store: Lessons from Eno and Björk – Are albums as apps gimmicks or do they provide real value?

- Participatory Culture: The Discourse of Pitchfork – An analysis of ten years of music writing to extract themes.

Data Mining Music – a SXSW 2012 Panel Proposal

Posted by Paul in data, events, Music, music information retrieval, The Echo Nest on August 15, 2011

I’ve submitted a proposal for a SXSW 2012 panel called Data Mining Music. The PanelPicker page for the talk is here: Data Mining Music. If you feel so inclined feel free to comment and/or vote for the talk. I promise to fill the talk with all sorts of fun info that you can extract from datasets like the Million Song Dataset.

Here’s the abstract:

Data mining is the process of extracting patterns and knowledge from large data sets. It has already helped revolutionized fields as diverse as advertising and medicine. In this talk we dive into mega-scale music data such as the Million Song Dataset (a recently released, freely-available collection of detailed audio features and metadata for a million contemporary popular music tracks) to help us get a better understanding of the music and the artists that perform the music.

We explore how we can use music data mining for tasks such as automatic genre detection, song similarity for music recommendation, and data visualization for music exploration and discovery. We use these techniques to try to answers questions about music such as: Which drummers use click tracks to help set the tempo? or Is music really faster and louder than it used to be? Finally, we look at techniques and challenges in processing these extremely large datasets.

Questions answered:

- What large music datasets are available for data mining?

- What insights about music can we gain from mining acoustic music data?

- What can we learn from mining music listener behavior data?

- Who is a better drummer: Buddy Rich or Neil Peart?

- What are some of the challenges in processing these extremely large datasets?

Flickr photo CC by tristanf

Amazon strikes back

Last month we saw how Amazon had to change its Kindle iOS app to comply with Apple’s TOS. Amazon eliminated the ‘Kindle Store’ button making it harder for Kindle readers to purchase books. Today, Amazon has fought back by releasing the Amazon Kindle Cloud Reader – A pure HTML5 web application for reading books. The cloud reader lets you do anything that the native Kindle app does, including offline reading. And, since HTML5 apps are not subject to Apple’s TOS, the Kindle Cloud Reader brings back integration with the Kinde Store.

This may ultimately become the most viable route for music subscription services as well. Instead of creating native iOS apps, music services may look to create rich web apps instead. HTML5 is certainly capable enough, and soon audio support and local caching will be mature enough to support even the most sophisticated music listening app. MOG has already converted their main application to HTML5. I suspect more will follow suit. As HTML5 improves, we may see an exodus away from iOS. The more you tighten your grip, Apple, the more applications will slip through your fingers.

How are music services responding to Apple’s new TOS?

Posted by Paul in Music, recommendation on August 4, 2011

There’s been quite a bit of turmoil around how IOS developers can sell products and subscriptions within their IOS application. Apple says, essentially, if you sell stuff within your app you have to give Apple a 30% cut

There’s been quite a bit of turmoil around how IOS developers can sell products and subscriptions within their IOS application. Apple says, essentially, if you sell stuff within your app you have to give Apple a 30% cut and you can’t try to pass costs onto the customer by charging more for items purchased within an App. The cost for an item must be the same whether it was purchased through the app or through some other means. Update: In June, MacRumors reported that Apple updated its TOS so that content providers are now also free to charge whatever price they wish for content purchased outside of an App. Apple also says that you can no longer have a button or a link in your app to a website where a user can purchase content without giving Apple their 30% cut.

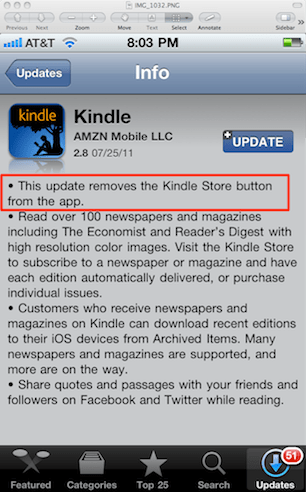

For most media industries,there is not enough left of the profit pie to allow Apple to take 30% of it. This has left most media companies in a quandary of how to continue to give their users a good experience, without bankrupting their company. Many folks looked toward Amazon to see how they would react. Amazon’s Kindle reader is used by millions of iPad and iPhone readers to purchase and read digital books. Amazon’s solution was simple. Last week they issued an update to their Kindle Reader IOS app that removed the Kindle Store button. After the update, The [Kindle Store] button is no longer present in the app. This means that users of the Kindle IOS app can no longer launch a book shopping session from within the Kindle app. Here’s the update:

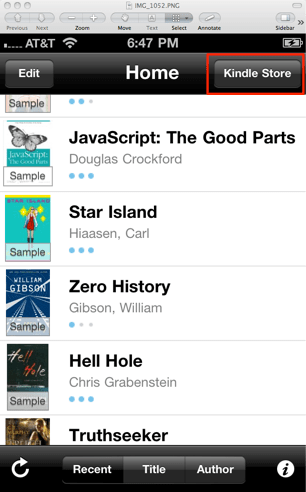

Before the update, the Kindle app looks like this, with a very visible Kindle Store button that will take you to the Kindle web store, where you can buy Kindle books:

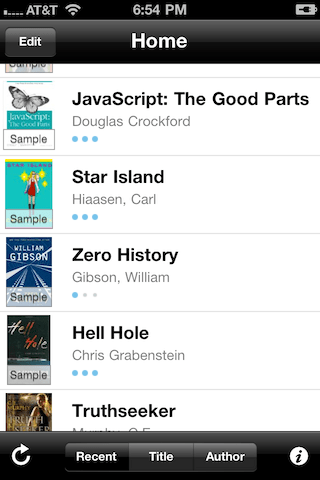

After the update, the Kindle App looks like this. The Kindle Store button is gone.

What are music services doing?

I was curious to see how various music subscription services were dealing with the same issue. I fired up the apps, checked for updates and this is what I found.

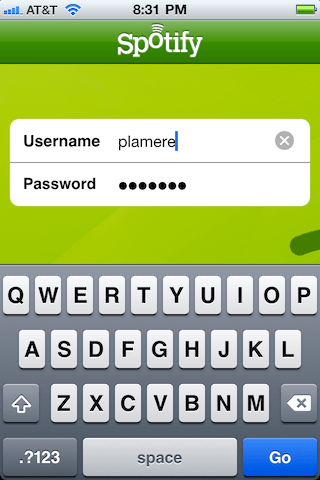

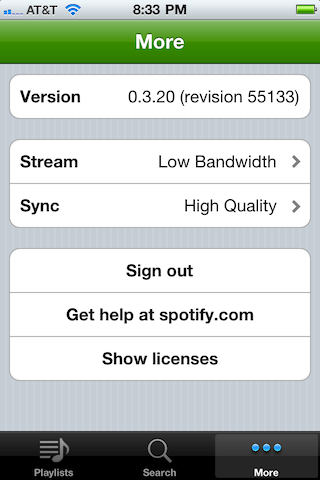

Spotify

Spotify updated their app to get rid of any in-app purchases or subscription links just like the Kindle. You can only listen to Spotify mobile if you already have a Spotify mobile account.

When you login to Spotify there is no option to register an account. Spotify just assumes that you have already registered and are ready to login in and start using the app:

Curiously, there is a ‘Get help at Spotify.com’ button on the More page of the app. This will open a web browser and bring you to the Spotify Help page, which puts you two clicks away from a ‘subscribe’ button. This must cut pretty close to Apple’s rules about links to web sites.

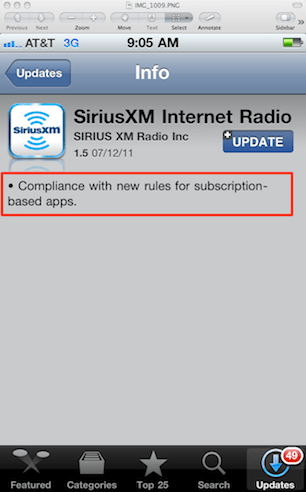

SiriusXM

As with Spotify, SiriusXM, removed any links back to their site. Only people that already have a SiriusXM account can use the SiriusXM app.

Rhapsody

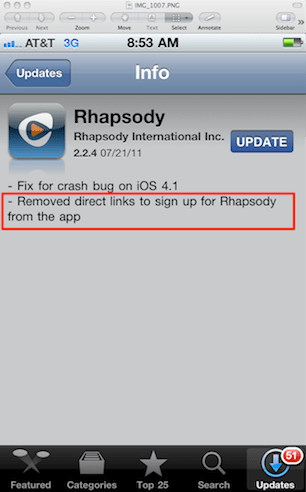

Same story for Rhapsody, there’s no way to get a subscription for Rhapsody within the Rhapsody Application.

MOG

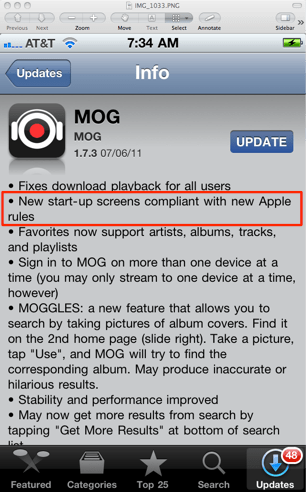

MOG issued in update in July that removed links to the MOG subscription portal.

Napster

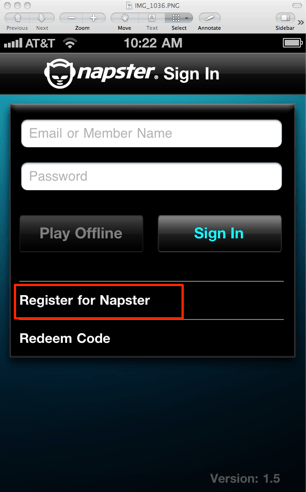

Interestingly enough, the very latest version of Napster happily allows you to register for Napster through the application. On the Sign In page there is a prominent Register for Napster button.

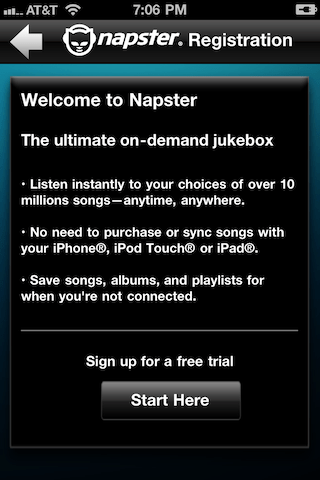

Pressing the button brings you to a Registration page where you can sign up for a 7-day free trial

I wonder what happens if a 7-day free trial user converts to a paying subscriber. Does Apple get 30% or is Napster hoping that no one notices?

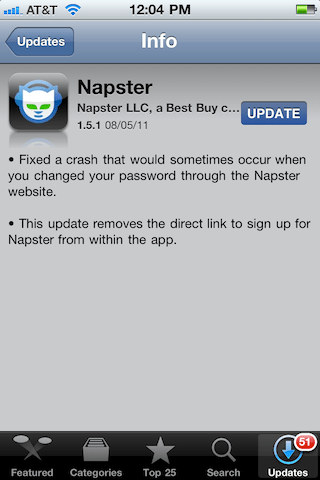

Update – A Napster update was released one day after this post was published that eliminates the direct signup link:

Slacker

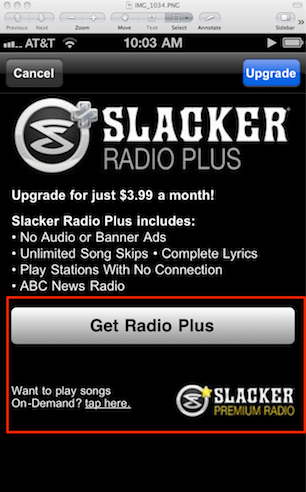

Slacker’s $3.99 a month Radio Plus product is included as a prominent upgrade in the Slacker app. If you hit the upgrade button you will get a form to fill out with all of your credit card info so they can start charging you the 4 bucks. The question is whether or not Apple is getting $1.20 of that 4 bucks.

Pandora

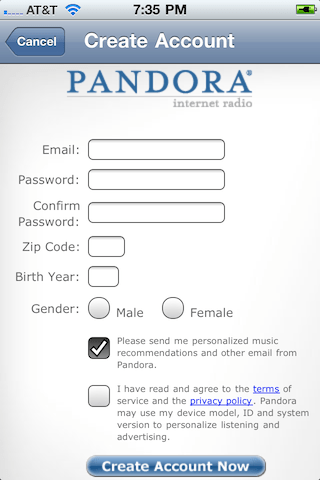

With Pandora you can create a free account through the mobile app, but there is no mention of a premium account, nor are there any links to Pandora.com as far as I can tell.

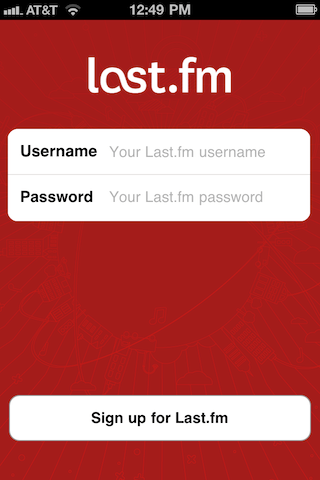

Last.fm

Just like Pandora, the Last.fm app will let you sign up for a non-premium account via the app and makes no mention or attempt to upsell you to a paid account:

Rdio

Rdio takes a similar approach to Pandora and Last.fm. It allows users to sign up for a 7 day free trial account via the app. It makes no mention and has no links to a premium subscription page. It is not clear to me what happens at the end of the trial period, whether they will prompt you to visit Rdio, or if they just say “Your free trial is over, thanks for listening”.

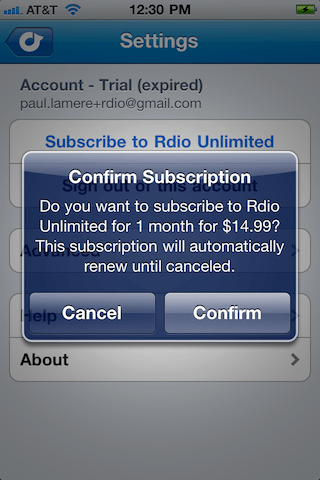

Update – It is a moving target out there. Rdio issued an update yesterday that now allows you to purchase a monthly subscription in the app. With the new version you can now click on the ‘Subscribe to Rdio Unlimited’. When you do you receive this confirmation dialog:

This allows you to purchase the Rdio subscription for $14.99, which just happens to be 33% more than an Rdio Unlimited subscription would cost if purchased directly from the web. Rdio is taking advantage of Apple’s recent relaxation of the rules and seeing how effective in-app subscription purchases stack up against cheaper out-of-app purchases. There’s a good LA Times article Rdio attempts to survive Apple’s subscription tax that describes Rdio’s approach to dealing with this issue.

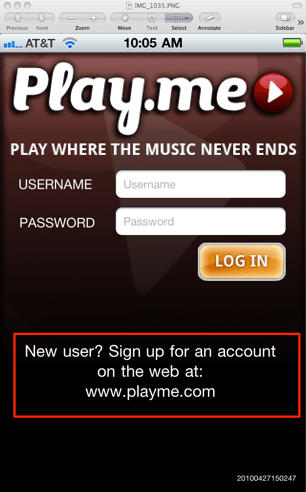

Playme

The latest version of Playme doesn’t have a button or link that brings you to the Playme subscription page. It does, however, display http://www.playme.com prominently on the sign in page so you can type the URL directly into your browser. I guess technically the words http://www.playme.com are not a link if you can’t click or tap it to go there.

Grooveshark

Grooveshark has never been timid of walking up to the line and stepping across it. The only way to get Grooveshark on an IOS device is to Jailbreak your device. With a Jailbroken version, Grooveshark doesn’t need to pay anyone for anything.

Conclusion

Apple has always been a company that prides itself on encouraging an excellent user experience. However, when Apple had to weigh a good user experience against potentially making 30% of every music subscription they decided to screw over the user and go for the pot of money. The reality, is, however, that no music streaming company will ever be able to afford to give Apple a 30% cut. The result is that these apps have to work around Apple’s rules, the result being a poor user experience, and no money for Apple. Hopefully, by the end of the year, Apple will look at the bottom line and realize that they’ve made no extra money from the 30% rule, and instead have encouraged the creation of a big streaming pile of music apps that make the user jump through all sorts of unnecessary hoops for no good reason. Note however, that the story isn’t over. Rdio is experimenting with in-app subscription purchases. If they are successful at this, in a few months time, perhaps we’ll see Spotify, Mog, Rhapsody and the others try the same thing.

How do you spell ‘Britney Spears’?

Posted by Paul in code, data, Music, music information retrieval, research, The Echo Nest on July 28, 2011

I’ve been under the weather for the last couple of weeks, which has prevented me from doing most things, including blogging. Luckily, I had a blog post sitting in my drafts folder almost ready to go. I spent a bit of time today finishing it up, and so here it is. A look at the fascinating world of spelling correction for artist names.

In today’s digital music world, you will often look for music by typing an artist name into a search box of your favorite music app. However this becomes a problem if you don’t know how to spell the name of the artist you are looking for. This is probably not much of a problem if you are looking for U2, but it most definitely is a problem if you are looking for Röyksopp, Jamiroquai or Britney Spears. To help solve this problem, we can try to identify common misspellings for artists and use these misspellings to help steer you to the artists that you are looking for.

In today’s digital music world, you will often look for music by typing an artist name into a search box of your favorite music app. However this becomes a problem if you don’t know how to spell the name of the artist you are looking for. This is probably not much of a problem if you are looking for U2, but it most definitely is a problem if you are looking for Röyksopp, Jamiroquai or Britney Spears. To help solve this problem, we can try to identify common misspellings for artists and use these misspellings to help steer you to the artists that you are looking for.

A spelling corrector in 21 lines of code

A good place for us to start is a post by Peter Norvig (Director of Research at Google) called ‘How to write a spelling corrector‘ which presents a fully operational spelling corrector in 21 lines of Python. (It is a phenomenal bit of code, worth the time studying it). At the core of Peter’s algorithm is the concept of the edit distance which is a way to represent the similarity of two strings by calculating the number of operations (inserts, deletes, replacements and transpositions) needed to transform one string into the other. Peter cites literature that suggests that 80 to 95% of spelling errors are within an edit distance of 1 (meaning that most misspellings are just one insert, delete, replacement or transposition away from the correct word). Not being satisfied with that accuracy, Peter’s algorithm considers all words that are within an edit distance of 2 as candidates for his spelling corrector. For Peter’s small test case (he wrote his system on a plane so he didn’t have lots of data nearby), his corrector covered 98.9% of his test cases.

Spell checking Britney

A few years ago, the smart folks at Google posted a list of Britney Spears spelling corrections that shows nearly 600 variants on Ms. Spears name collected in three months of Google searches. Perusing the list, you’ll find all sorts of interesting variations such as ‘birtheny spears’ , ‘brinsley spears’ and ‘britain spears’. I suspect that some these queries (like ‘Brandi Spears’) may actually not be for the pop artist. One curiosity in the list is that although there are 600 variations on the spelling of ‘Britney’ there is exactly one way that ‘spears’ is spelled. There’s no ‘speers’ or ‘spheres’, or ‘britany’s beers’ on this list.

One thing I did notice about Google’s list of Britneys is that there are many variations that seem to be further away from the correct spelling than an edit distance of two at the core of Peter’s algorithm. This means that if you give these variants to Peter’s spelling corrector, it won’t find the proper spelling. Being an empiricist I tried it and found that of the 593 variants of ‘Britney Spears’, 200 were not within an edit distance of two of the proper spelling and would not be correctable. This is not too surprising. Names are traditionally hard to spell, there are many alternative spellings for the name ‘Britney’ that are real names, and many people searching for music artists for the first time may have only heard the name pronounced and have never seen it in its written form.

Making it better with an artist-oriented spell checker

A 33% miss rate for a popular artist’s name seems a bit high, so I thought I’d see if I could improve on this. I have one big advantage that Peter didn’t. I work for a music data company so I can be pretty confident that all the search queries that I see are going to be related to music. Restricting the possible vocabulary to just artist names makes things a whole lot easier. The algorithm couldn’t be simpler. Collect the names of the top 100K most popular artists. For each artist name query, find the artist name with the smallest edit distance to the query and return that name as the best candidate match. This algorithm will let us find the closest matching artist even if it is has an edit distance of more than 2 as we see in Peter’s algorithm. When I run this against the 593 Britney Spears misspellings, I only get one mismatch – ‘brandi spears’ is closer to the artist ‘burning spear’ than it is to ‘Britney Spears’. Considering the naive implementation, the algorithm is fairly fast (40 ms per query on my 2.5 year old laptop, in python).

Looking at spelling variations

With this artist-oriented spelling checker in hand, I decided to take a look at some real artist queries to see what interesting things I could find buried within. I gathered some artist name search queries from the Echo Nest API logs and looked for some interesting patterns (since I’m doing this at home over the weekend, I only looked at the most recent logs which consists of only about 2 million artist name queries).

Artists with most spelling variations

Not surprisingly, very popular artists are the most frequently misspelled. It seems that just about every permutation has been made in an attempt to spell these artists.

- Michael Jackson – Variations: michael jackson, micheal jackson, michel jackson, mickael jackson, mickal jackson, michael jacson, mihceal jackson, mickeljackson, michel jakson, micheal jaskcon, michal jackson, michael jackson by pbtone, mical jachson, micahle jackson, machael jackson, muickael jackson, mikael jackson, miechle jackson, mickel jackson, mickeal jackson, michkeal jackson, michele jakson, micheal jaskson, micheal jasckson, micheal jakson, micheal jackston, micheal jackson just beat, micheal jackson, michal jakson, michaeljackson, michael joseph jackson, michael jayston, michael jakson, michael jackson mania!, michael jackson and friends, michael jackaon, micael jackson, machel jackson, jichael mackson

- Justin Bieber – Variations: justin bieber, justin beiber, i just got bieber’ed by, justin biber, justin bieber baby, justin beber, justin bebbier, justin beaber, justien beiber, sjustin beiber, justinbieber, justin_bieber, justin. bieber, justin bierber, justin bieber<3 4 ever<3, justin bieber x mstrkrft, justin bieber x, justin bieber and selens gomaz, justin bieber and rascal flats, justin bibar, justin bever, justin beiber baby, justin beeber, justin bebber, justin bebar, justien berbier, justen bever, justebibar, jsustin bieber, jastin bieber, jastin beiber, jasten biber, jasten beber songs, gestin bieber, eiine mainie justin bieber, baby justin bieber,

- Red Hot Chili Peppers – Variations: red hot chilli peppers, the red hot chili peppers, red hot chilli pipers, red hot chilli pepers, red hot chili, red hot chilly peppers, red hot chili pepers, hot red chili pepers, red hot chilli peppears, redhotchillipeppers, redhotchilipeppers, redhotchilipepers, redhot chili peppers, redhot chili pepers, red not chili peppers, red hot chily papers, red hot chilli peppers greatest hits, red hot chilli pepper, red hot chilli peepers, red hot chilli pappers, red hot chili pepper, red hot chile peppers

- Mumford and Sons – Variations: mumford and sons, mumford and sons cave, mumford and son, munford and sons, mummford and sons, mumford son, momford and sons, modfod and sons, munfordandsons, munford and son, mumfrund and sons, mumfors and sons, mumford sons, mumford ans sons, mumford and sonns, mumford and songs, mumford and sona, mumford and, mumford &sons, mumfird and sons, mumfadeleord and sons

- Katy Perry – Even an artist with a seemingly very simple name like Katy Perry has numerous variations: katy perry, katie perry, kate perry, kathy perry, katy perry ft.kanye west, katty perry, katy perry i kissed a girl, peacock katy perry, katyperry, katey parey, kety perry, kety peliy, katy pwrry, katy perry-firework, katy perry x, katy perry, katy perris, katy parry, kati perry, kathy pery, katey perry, katey perey, katey peliy, kata perry, kaity perry

Some other most frequently misspelled artists:

- Britney Spears

- Linkin Park

- Arctic Monkeys

- Katy Perry

- Guns N’ Roses

- Nicki Minaj

- Muse

- Weezer

- U2

- Oasis

- Moby

- Flyleaf

- Seether

- byran adams – ryan adams

- Underworld – Uverworld

Finding soundtracks on spotify, mog and rdio

Posted by Paul in Music, recommendation on July 11, 2011

Ethan Kaplan over at hypebot had a problem with how hard it is to find soundtracks by John Williams on music services like Spotify and Rdio. Here’s what he said:

Try going to Spotify and browsing movie soundtracks. I’ll wait.

Try searching for John Williams. He is not a guitarist, but that is what comes up mixed in with all of the soundtrack work he has done.

And this is not something unique to Spotify, but also endemic to Rdio and Mog. Mog at least has a page of curated soundtracks, but its just as hard to find them “in the wild” as it is on Spotify. The same applies to Rdio.

Well, of course, if you search for John Williams you’ll get music by both the movie composer and by the guitarist. That is only natural, because, you may really want the music by the guitarist and not music by the composer. Let’s see what happens if you go one step further than Ethan did and search for “john williams soundstracks”. Here are the results on Spotify:

Not surprisingly, there are hundreds of matches of John Williams and soundtracks. Similar results with Rdio:

Lots of John Williams soundtrack results. Rdio even offers human curated playlists filled with soundtracks. What could be better? Likewise, if you just search for soundtracks there are lots of hits:

So I don’t buy Ethan’s premise that it is hard to find soundtracks or music by the movie composer John Williams. However, Ethan’s point still stands: finding new music on current generation music services really sucks. The next generation music services need to do much better to help people explore and discover new music. Music exploration should be fun and yet we are doomed to try to explore and discover music using a tool that looks like an accountant’s spreadsheet.

Finding duplicate songs in your music collection with Echoprint

Posted by Paul in code, Music, The Echo Nest on June 25, 2011

This week, The Echo Nest released Echoprint – an open source music fingerprinting and identification system. A fingerprinting system like Echoprint recognizes music based only upon what the music sounds like. It doesn’t matter what bit rate, codec or compression rate was used (up to a point) to create a music file, nor does it matter what sloppy metadata has been attached to a music file, if the music sounds the same, the music fingerprinter will recognize that. There are a whole bunch of really interesting apps that can be created using a music fingerprinter. Among my favorite iPhone apps are Shazam and Soundhound – two fantastic over-the-air music recognition apps that let you hold your phone up to the radio and will tell you in just a few seconds what song was playing. It is no surprise that these apps are top sellers in the iTunes app store. They are the closest thing to magic I’ve seen on my iPhone.

This week, The Echo Nest released Echoprint – an open source music fingerprinting and identification system. A fingerprinting system like Echoprint recognizes music based only upon what the music sounds like. It doesn’t matter what bit rate, codec or compression rate was used (up to a point) to create a music file, nor does it matter what sloppy metadata has been attached to a music file, if the music sounds the same, the music fingerprinter will recognize that. There are a whole bunch of really interesting apps that can be created using a music fingerprinter. Among my favorite iPhone apps are Shazam and Soundhound – two fantastic over-the-air music recognition apps that let you hold your phone up to the radio and will tell you in just a few seconds what song was playing. It is no surprise that these apps are top sellers in the iTunes app store. They are the closest thing to magic I’ve seen on my iPhone.

In addition to the super sexy applications like Shazam, music identification systems are also used for more mundane things like copyright enforcement (helping sites like Youtube keep copyright violations out of the intertubes), metadata cleanup (attaching the proper artist, album and track name to every track in a music collection), and scan & match like Apple’s soon to be released iCloud music service that uses music identification to avoid lengthy and unnecessary music uploads. One popular use of music identification systems is to de-duplicate a music collection. Programs like tuneup will help you find and eliminate duplicate tracks in your music collection.

This week I wanted to play around with the new Echoprint system, so I decided I’d write a program that finds and reports duplicate tracks in my music collection. Note: if you are looking to de-duplicate your music collection, but you are not a programmer, this post is *not* for you, go and get tuneup or some other de-duplicator. The primary purpose of this post is to show how Echoprint works, not to replace a commercial system.

How Echoprint works

Echoprint, like many music identification services is a multi-step process: code generation, ingestion and lookup. In the code generation step, musical features are extracted from audio and encoded into a string of text. In the ingestion step, codes for all songs in a collection are generated and added to a searchable database. In the lookup step, the codegen string is generated for an unknown bit of audio and is used as a fuzzy query to the database of previously ingested codes. If a suitably high-scoring match is found, the info on the matching track is returned. The devil is in the details. Generating a short high level representation of audio that is suitable for searching that is insensitive to encodings, bit rate, noise and other transformations is a challenge. Similarly challenging is representing a code in a way that allows for high speed querying and allows for imperfect matching of noisy codes.

Echoprint consists of two main components: echoprint-codegen and echoprint-server.

Code Generation

echoprint-codegen is responsible for taking a bit of audio and turning it into an echoprint code. You can grab the source from github and build the binary for your local platform. The binary will take an audio file as input and give output a block of JSON that contains song metadata (that was found in the ID3 tags in the audio) along with a code string. Here’s an example:

plamere$ echoprint-codegen test/unison.mp3 0 10

[

{"metadata":{"artist":"Bjork",

"release":"Vespertine",

"title":"Unison",

"genre":"",

"bitrate":128,"sample_rate":44100, "duration":405,

"filename":"test/unison.mp3",

"samples_decoded":110296,

"given_duration":10, "start_offset":1,

"version":4.11,

"codegen_time":0.024046,

"decode_time":0.641916},

"code_count":174,

"code":"eJyFk0uyJSEIBbcEyEeWAwj7X8JzfDvKnuTAJIojWACwGB4QeM\

HWCw0vLHlB8IWeF6hf4PNC2QunX3inWvDCO9WsF7heGHrhvYV3qvPEu-\

87s9ELLi_8J9VzknReEH1h-BOKRULBwyZiEulgQZZr5a6OS8tqCo00cd\

p86ymhoxZrbtQdgUxQvX5sIlF_2gUGQUDbM_ZoC28DDkpKNCHVkKCgpd\

OHf-wweX9adQycnWtUoDjABumQwbJOXSZNur08Ew4ra8lxnMNuveIem6\

LVLQKsIRLAe4gbj5Uxl96RpdOQ_Noz7f5pObz3_WqvEytYVsa6P707Jz\

j4Oa7BVgpbKX5tS_qntcB9G--1tc7ZDU1HamuDI6q07vNpQTFx22avyR",

"tag":0}

]

In this example, I’m only fingerprinting the first 10 second of the song to conserve space. The code string is just a base64 encoding of a zlib compression of the original code string, which is a hex encoded series of ASCII numbers. A full version of this code is what is indexed by the lookup server for fingerprint queries. Codegen is quite fast. It scans audio at roughly 250x real time per processor after decoding and resampling to 11025 Hz. This means a full song can be scanned in less than 0.5s on an average computer, and an amount of audio suitable for querying (30s) can be scanned in less than 0.04s. Decoding from MP3 will be the bottleneck for most implementations. Decoders like mpg123 or ffmpeg can decode 30s mp3 audio to 11025 PCM in under 0.10s.

The Echoprint Server

The Echoprint server is responsible for maintaining an index of fingerprints of (potentially) millions of tracks and serving up queries. The lookup server uses the popular Apache Solr as the search engine. When a query arrives, the codes that have high overlap with the query code are retrieved using Solr. The lookup server then filters through these candidates and scores them based on a number of factors such as the number of codeword matches, the order and timing of codes and so on. If the best matching code has a high enough score, it is considered a hit and the ID and any associated metadata is returned.

To run a server, first you ingest and index full length codes for each audio track of interest into the server index. To perform a lookup, you use echoprint-codegen to generate a code for a subset of the file (typically 30 seconds will do) and issue that as a query to the server.

The Echo Nest hosts a lookup server, so for many use cases you won’t need to run your own lookup server. Instead , you can make queries to the Echo Nest via the song/identify call. (We also expect that many others may run public echoprint servers as well).

Creating a de-duplicator

With that quick introduction on how Echoprint works let’s look at how we could create a de-duplicator. The core logic is extremely simple:

create an empty echoprint-server

foreach mp3 in my-music-collection:

code = echoprint-codegen(mp3) // generate the code

result = echoprint-server.query(code) // look it up

if result: // did we find a match?

print 'duplicate for', mp3, 'is', result

else: // no, so ingest the code

echoprint-server.ingest(mp3, code)

We create an empty fingerprint database. For each song in the music collection we generate an Echoprint code and query the server for a match. If we find one, then the mp3 is a duplicate and we report it. Otherwise, it is a new track, so we ingest the code for the new track into the echoprint server. Rinse. Repeat.

I’ve written a python program dedup.py to do just this. Being a cautious sort, I don’t have it actually delete duplicates, but instead, I have it just generate a report of duplicates so I can decide which one I want to keep. The program also keeps track of its state so you can re-run it whenever you add new music to your collection.

Here’s an example of running the program:

% python dedup.py ~/Music/iTunes

1 1 /Users/plamere/Music/misc/ABBA/Dancing Queen.mp3

( lines omitted...)

173 41 /Users/plamere/Music/misc/Missy Higgins - Katie.mp3

174 42 /Users/plamere/Music/misc/Missy Higgins - Night Minds.mp3

175 43 /Users/plamere/Music/misc/Missy Higgins - Nightminds.mp3

duplicate /Users/plamere/Music/misc/Missy Higgins - Nightminds.mp3

/Users/plamere/Music/misc/Missy Higgins - Night Minds.mp3

176 44 /Users/plamere/Music/misc/Missy Higgins - This Is How It Goes.mp3

Dedup.py print out each mp3 as it processes it and as it finds a duplicate it reports it. It also collects a duplicate report in a file in pblml format like so:

duplicate <sep> iTunes Music/Bjork/Greatest Hits/Pagan Poetry.mp3 <sep> original <sep> misc/Bjork Radio/Bjork - Pagan Poetry.mp3 duplicate <sep> iTunes Music/Bjork/Medulla/Desired Constellation.mp3 <sep> original <sep> misc/Bjork Radio/Bjork - Desired Constellation.mp3 duplicate <sep> iTunes Music/Bjork/Selmasongs/I've Seen It All.mp3 <sep> original <sep> misc/Bjork Radio/Bjork - I've Seen It All.mp3

Again, dedup.py doesn’t actually delete any duplicates, it will just give you this nifty report of duplicates in your collection.

Trying it out

If you want to give dedup.py a try, follow these steps:

- Download, build and install echoprint-codegen

- Download, build, install and run the echoprint-server

- Get dedup.py.

- Edit line 10 in dedup.py to set the sys.path to point at the echoprint-server API directory

- Edit line 13 in dedup.py to set the _codegen_path to point at your echoprint-codegen executable

% python dedup.py ~/Music

This will find all of the dups and write them to the dedup.dat file. It takes about 1 second per song. To restart (this will delete your fingerprint database) run:

% python dedup.py --restart

Note that you can actually run the dedup process without running your own echoprint-server (saving you the trouble of installing Apache-Solr, Tokyo cabinet and Tokyo cabinet). The downside is that you won’t have any persistent server, which means that you’ll not be able to incrementally de-dup your collection – you’ll need to do it in all in one pass. To use the local mode, just add local-True to the fp.py calls. The index is then kept in memory, no solr or Tokyo tyrant is needed.

Wrapping up

dedup.py is just one little example of the kind of application that developers will be able to create using Echoprint. I expect to see a whole lot more in the next few months. Before Echoprint, song identification was out of the reach of the typical music application developer, it was just too expensive. Now with Echoprint, anyone can incorporate music identification technology into their apps. The result will be fewer headaches for developers and much better music applications for everyone.

Visualizing the active years of popular artists

Posted by Paul in data, Music, The Echo Nest, visualization on June 21, 2011

This week the Echo Nest is extending the data returned for an artist to include the active years for an artist. For thousands of artists you will be able to retrieve the starting and ending date for an artists career. This may include multiple ranges as groups split and get back together for that last reunion tour. Over the weekend, I spent a few hours playing with the data and built a web-based visualization that shows you the active years for the top 1000 or so hotttest artists.

The visualization shows the artists in order of their starting year. You can see the relatively short careers of artists like Robert Johnson and Sam Cooke, and the extremely long careers of artists like The Blind Boys of Alabama and Ennio Morricone. The color of an artist’s range bar is proportional to the artist’s hotttnesss. The hotter the artist, the redder the bar. Thanks to 7Digital, you can listen to a sample of the artist by clicking on the artist. To create the visualization I used Mike Bostock’s awesome D3.js (Data Driven Documents) library.

It is fun to look at some years active stats for the top 1000 hotttest artists:

- Average artist career length: 17 years

- Percentage of top artists that are still active: 92%

- Longest artist career: The Blind Boys of Alabama – 73 Years and still going

- Gone but not forgotten – Robert Johnson – Hasn’t recorded since 1938 but still in the top 1,000

- Shortest Career – Joy Division – Less than 4 Years of Joy

- Longest Hiatus – The Cars – 22 years – split in 1988, but gave us just what we needed when they got back together in 2010

- Can’t live with’em, can’t live without ’em – Simon and Garfunkel – paired up 9 separate times

- Newest artist in the top 1000 – Birdy – First single released in March 2011

Check out the visualization here: Active years for the top 1000 hotttest artists and read more about the years-active support on the Echo Nest blog

Reidentification of artists and genres in the KDD cup data

Posted by Paul in data, recommendation, research on June 21, 2011

Back in February I wrote a post about the KDD Cup ( an annual Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery competition), asking whether this year’s cup was really music recommendation since all the data identifying the music had been anonymized. The post received a number of really interesting comments about the nature of recommendation and whether or not context and content was really necessary for music recommendation, or was user behavior all you really needed. A few commenters suggested that it might be possible de-anonymize the data using a constraint propagation technique.

Many voiced an opinion that such de-anonymizing of the data to expose user listening habits would indeed be unethical. Malcolm Slaney, the researcher at Yahoo! who prepared the dataset offered the plea:

Many voiced an opinion that such de-anonymizing of the data to expose user listening habits would indeed be unethical. Malcolm Slaney, the researcher at Yahoo! who prepared the dataset offered the plea:

If you do de-anonymize the data please don’t tell anybody. We’ll NEVER be able to release data again.

As far as I know, no one has de-anonymized the KDD Cup dataset, however, researcher Matthew J. H. Rattigan of The University of Massachusetts at Amherst has done the next best thing. He has published a paper called Reidentification of artists and genres the KDD cup that shows that by analyzing at the relational structures within the dataset it is possible to identify the artists, albums, tracks and genres that are used in the anonymized dataset. Here’s an excerpt from the paper that gives an intuitive description of the approach:

For example, consider Artist 197656 from the Track 1 data. This artist has eight albums described by different combinations of ten genres. Each album is associated with several tracks, with track counts ranging from 1 to 69. We make the assumption that these albums and tracks were sampled without replacement from the discography of some real artist on the Yahoo! Music website. Furthermore, we assume that the connections between genres and albums are not sampled; that is, if an album in the KDD Cup dataset is attached to three genres, its real-world counterpart has exactly three genres (or “Categories”, as they are known on the Yahoo! Music site).

Under the above assumptions, we can compare the unlabeled KDD Cup artist with real-world Yahoo! Music artists in order to find a suitable match. The band Fischer Z, for example, is an unsuitable match, as their online discography only contains seven albums. An artist such as Meatloaf certainly has enough albums (56) to be a match, but none of those albums contain more than 31 tracks. The entry for Elvis Presley contains 109 albums, 17 of which boast 69 or more tracks; however, there is no consistent assignment of genres that satisfies our assumptions. The band Tool, however, is compatible with Artist 197656. The Tool discography contains 19 albums containing between 0 and 69 tracks. These albums are described by exactly 10 genres, which can be assigned to the unlabeled KDD Cup genres in a consistent manner. Furthermore, the match is unique: of the 134k artists in our labeled dataset, Tool is the only suitable match for Artist 197656.

Of course it is impossible for Matthew to evaluate his results directly, but he did create a number of synthetic, anonymized datasets draw from Yahoo and was able to demonstrate very high accuracy for the top artists and a 62% overall accuracy.

The motivation for this type of work is not to turn the KDD cup dataset into something that music recommendation researchers could use, but instead is to get a better understanding of data privacy issues. By understanding how large datasets can be de-anonymized, it will be easier for researchers in the future to create datasets that won’t be easily yield their hidden secrets. The paper is an interesting read – so since you are done doing all of your reviews for RecSys and ISMIR, go ahead and give it a read: https://www.cs.umass.edu/publication/docs/2011/UM-CS-2011-021.pdf. Thanks to @ocelma for the tip.