Archive for category The Echo Nest

Something is fishy with this recommender

Posted by Paul in Music, recommendation, research, The Echo Nest on April 1, 2009

In my rather long winded post on the problems with current music recommenders, I pointed out the Harry Potter Effect. Collaborative Filtering recommenders tend to recommend things that are popular which makes those items even more popular, creating a feedback loop – (or as the podcomplex calls it – the similarity vortex) that results in certain items becoming extremely popular at the expense of overall diversity. (For an interesting demonstration of this effect, see ‘Online monoculture and the end of the niche‘).

In my rather long winded post on the problems with current music recommenders, I pointed out the Harry Potter Effect. Collaborative Filtering recommenders tend to recommend things that are popular which makes those items even more popular, creating a feedback loop – (or as the podcomplex calls it – the similarity vortex) that results in certain items becoming extremely popular at the expense of overall diversity. (For an interesting demonstration of this effect, see ‘Online monoculture and the end of the niche‘).

Oscar sent me an example of this effect. At the popular British online music store HMV, a rather large fraction of artists recommendations point to the Kings of Leon. Some examples:

- PJ Harvey

- U2

- The Beatles

- Franz Ferdinand

- Amy Winehouse

- The Rolling Stones

- Fratellis

- Last Shadow of Puppets

- Fleet Foxes

- Roxy Music

- Green Day

- Newton Faulkner

- Paul Weller

- Guns’N’Roses

- Quireboys

- Nickelback

- Bon Iver

- Emerson, Lake and Palmer

- Miley Cyrus

- Nirvana

- Led Zeppelin

Oscar points out that even for albums that haven’t been released, HMV will tell you that ‘customers that bought the new unreleased album by Depeche Mode also bought the Kings of Leon’. Of course it is no surprise that if you look at the HMV bestsellers, The Kings Of Leon is way up there at position #3.

At first blush, this does indeed look like a classic example of the Harry Potter Effect, but I’m a bit suspicious that what we are seeing is not an example of a feedback loop, but is an example of shilling – using the recommender to explicitly promote a particular item. It may be that HMV has decided to hardwire a slot in their ‘customers who bought this also bought’ section to point to an item that they are trying to promote – perhaps due to a sweetheart deal with a music label. I don’t have any hard evidence of this, but when you look at the wide variety of artists that point to Kings of Leon – from Miley Cyrus, to Led Zeppelin and Nirvana it is hard to imagine that this is a result of natural collaborative filtering. Music promotion that disguises itself as music recommendation has been around for about as long as there have been people looking for new music. Payola schemes have dogged radio for decades. It is not hard to believe that this type of dishonest marketing will find its way into recommender systems. We’ve already seen the rise of ‘search engine optimization’ companies that will get your web site on the first page of google search results – it won’t be long before we see a recommender engine optimizer industry that will promote your items by manipulating recommenders. It may already be happening now, and we just don’t know about it. The next time you get a recommendation for The Kings of Leon because you like The Rolling Stones, ask yourself if this is a real and honest recommendation or are they just trying to sell you something.

Help! My iPod thinks I’m emo – Part 1

Posted by Paul in Music, recommendation, research, The Echo Nest on March 26, 2009

At SXSW 2009, Anthony Volodkin and I presented a panel on music recommendation called “Help! My iPod thinks I’m emo”. Anthony and I share very different views on music recommendation. You can read Anthony’s notes for this session at his blog: Notes from the “Help! My iPod Thinks I’m Emo!” panel. This is Part 1 of my notes – and my viewpoints on music recommendation. (Note that even though I work for The Echo Nest, my views may not necessarily be the same as my employer).

The SXSW audience is a technical audience to be sure, but they are not as immersed in recommender technology as regular readers of MusicMachinery, so this talk does not dive down into hard core tech issues, instead it is a lofty overview of some of the problems and potential solutions for music recommendation. So lets get to it.

Music Recommendation is Broken.

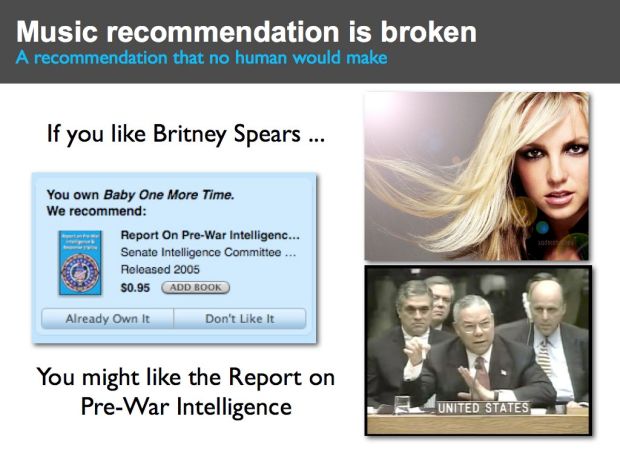

Even though Anthony and I disagree about a number of things, one thing that we do agree on is that music recommendation is broken in some rather fundamental ways. For example, this slide shows a recommendation from iTunes (from a few years back). iTunes suggests that if I like Britney Spears’ “Hit Me Baby One more time” that I might also like the “Report on Pre-War Intelligence for the Iraq war”.

Clearly this is a broken recommendation – this is a recommendation no human would make. Now if you’ve spent anytime visiting music sites on the web you’ve likely seen recommendations just as bad as this. Sometimes music recommenders just get it wrong – and they get it wrong very badly. In this talk we are going to talk about how music recommenders work, why they make such dumb mistakes, and some of the ideas coming from researchers and innovators like Anthony to fix music discovery.

Why do we even care about music recommendation and discovery?

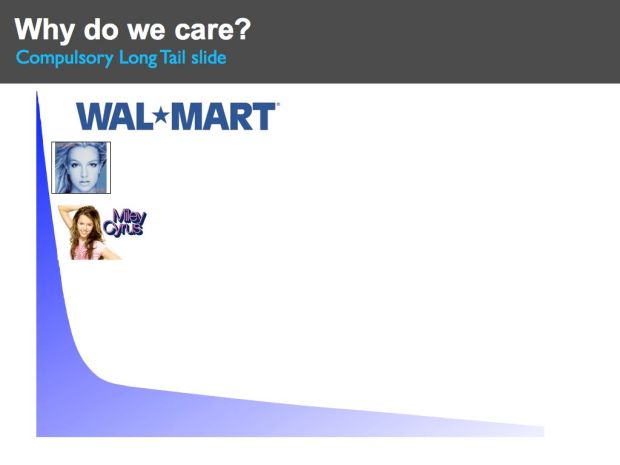

The world of music has changed dramatically. When I was growing up, a typical music store had on the order of 1,000 unique artists to chose from. Now, online music stores like iTunes have millions of unique songs to chose from. Myspace has millions of artists, and the P2P networks have billions of tracks available for download. We are drowning in a sea of music. And this is just the beginning. In a few years time the transformation to digital, online music will be complete. All recorded music will be online – every recording of every performance of every artist, whether they are a mainstream artist or a garage band or just a kid with a laptop will be uploaded to the web. There will be billions of tracks to chose from, with millions more arriving every week. With all this music to chose from, this should be a music nirvana – we should all be listening to new and interesting music.

With all this music, classic long tail economics apply. Without the constraints of physical space, music stores no longer need to focus on the most popular artists. There should be less of a focus on the hits and the megastars. With unlimited virtual space, we should see a flattening of the long tail – music consumption should shift to less popular artists. This is good for everyone. It is good for business – it is probably cheaper for a music store to sell a no-name artist than it is to sell the latest Miley Cyrus track. It is good for the artist – there are millions of unknown artists that deserve a bit of attention, and it is good for the listener. Listeners get to listen to a larger variety of music, that better fits their taste, as opposed to music designed and produced to appeal to the broadest demographics possible. So with the increase in available music we should see less emphasis on the hits. In the future, with all this music, our music listening should be less like Walmart and more like SXSW. But is this really happening? Lets take a look.

The state of music discovery

If we look at some of the data from Nielsen Soundscan 2007 we see that although there were more than 4 million tracks sold only 1% of those tracks accounted for 80% of sales. What’s worse, a whopping 13% of all sales are from American Idol or Disney Artists. Clearly we are still focusing on the hits. One must ask, what is going on here? Was Chris Anderson wrong? I really don’t think so. Anderson says that to make the long tail ‘work’ you have to do two things (1) Make everything available and (2) Help me find it. We are certainly on the road to making everything available – soon all music will be online. But I think we are doing a bad job on step (2) help me find it. Our music recommenders are *not* helping us find music, in fact current music recommenders do the exact opposite, they tend to push us toward popular artists and limit the diversity of recommendations. Music recommendation is fundamentally broken, instead of helping us find music in the long tail they are doing the exact opposite. They are pushing us to popular content. To highlight this take a look at the next slide.

Help! I’m stuck in the head

This is a study done by Dr. Oscar Celma of MTG UPF (and now at BMAT). Oscar was interested in how far into the long tail a recommender would get you. He divided the 245,000 most popular artists into 3 sections of equal sales – the short head, with 83 artists, the mid tail with 6,659 artists, and the long tail with 239,798 artists. He looked at recommendations (top 20 similar artists) that start in the short head and found that 48% of those recommendations bring you right back to the short head. So even though there are nearly a quarter million artists to chose from, 48% of all recommendations are drawn from a pool of the 83 most popular artists. The other 52% of recommendations are drawn from the mid-tail. No recommendations at all bring you to the long tail. The nearly 240,000 artists in the long tail are not reachable directly from the short head. This demonstrates the problem with commercial recommendation – it focuses people on the popular at the expense of the new and unpopular.

Let’s take a look at why recommendation is broken.

The Wisdom of Crowds

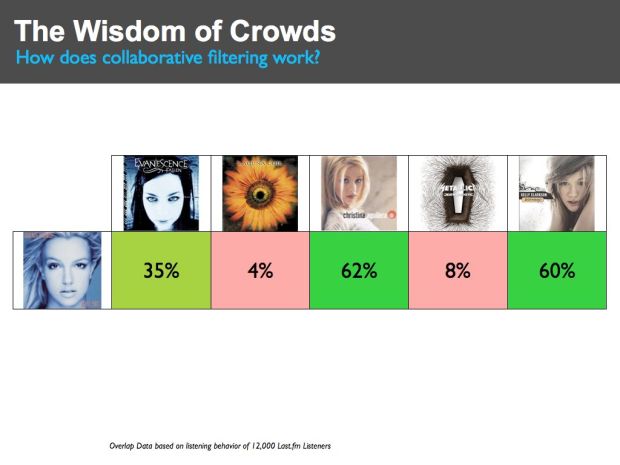

First lets take a look at how a typical music recommender works. Most music recommenders use a technique called Collaborative Filtering (CF). This is the type of recommendation you get at Amazon where they tell you that ‘people who bought X also bought Y’. The core of a CF recommender is actually quite simple. At the heart of the recommender is typically an item-to-item similarity matrix that is used to show how similar or dissimilar items are. Here we see a tiny excerpt of such a matrix. I constructed this by looking at the listening patterns of 12,000 last.fm listeners and looking at which artists have overlapping listeners. For instance, 35% of listeners that listen to Britney Spears also listen to Evancescence, while 62% also listen to Christina Aguilera. The core of a CF recommender is such a similarity matrix constructed by looking at this listener overlap. If you like Britney Spears, from this matrix we could recommend that you might like Christana and Kelly Clarkson, and we’d recommend that you probably wouldn’t like Metallica or Lacuna Coil.

CF recommenders have a number of advantages. First, they work really well for popular artists. When there are lots of people listening to a set of artists, the overlap is a good indicator of overall preference. Secondly, CF systems are fairly easy to implement. The math is pretty straight forward and conceptually they are very easy to understand. Of course, the devil is in the details. Scaling a CF system to work with millions of artists and billions of tracks for millions of users is an engineering challenge. Still, it is no surprise that CF systems are so widely used. They give good recommendations for popular items and they are easy to understand and implement. However, there are some flaws in CF systems that ultimately makes them not suitable for long-tail music recommendation. Let’s take a look at some of the issues.

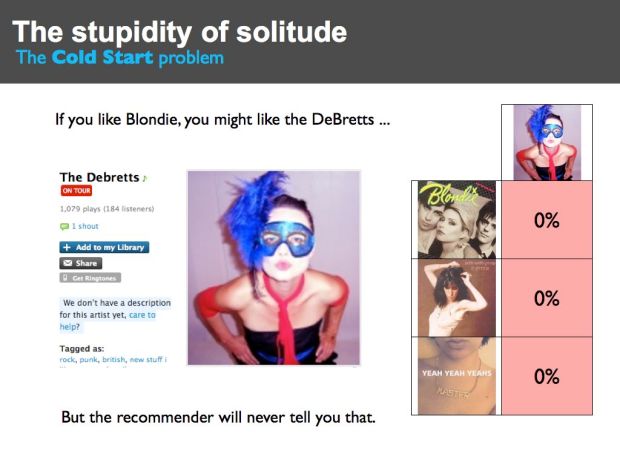

The Stupidity of Solitude

The DeBretts are a long tail artist. They are a punk band with a strong female vocalist that is reminiscent of Blondie or Patti Smith. (Be sure to listen to their song ‘The Rage’) .The DeBretts haven’t made it big yet. At last.fm they have about 200 listeners. They are a really good band and deserve to be heard. But if you went to an online music store like iTunes that uses a Collaborative Filterer to recommend music, you would *never* get a recommendation for the DeBretts. The reason is pretty obvious. The DeBretts may appeal to listeners that like Blondie, but even if all of the DeBretts listeners listen to Blondie the percentage of Blondie listeners that listen to the DeBretts is just too low. If Blondie has a million listeners then the maximum potential overlap(200/1,000,000) is way too small to drive any recommendations from Blondie to the DeBretts. The bottom line is that if you like Blondie, even though the DeBretts may be a perfect recommendation for you, you will never get this recommendation. CF systems rely on the wisdom of the crowds, but for the DeBretts, there is no crowd and without the crowd there is no wisdom. Among those that build recommender systems, this issue is called ‘the cold start’ problem. It is one of the biggest problems for CF recommenders. A CF-based recommender cannot make good recommendations for new and unpopular items.

Clearly we can see that this cold start problem is going to make it difficult for us to find new music in the long tail. The cold start problem is one of the main reasons why are recommenders are still’ stuck in the head’.

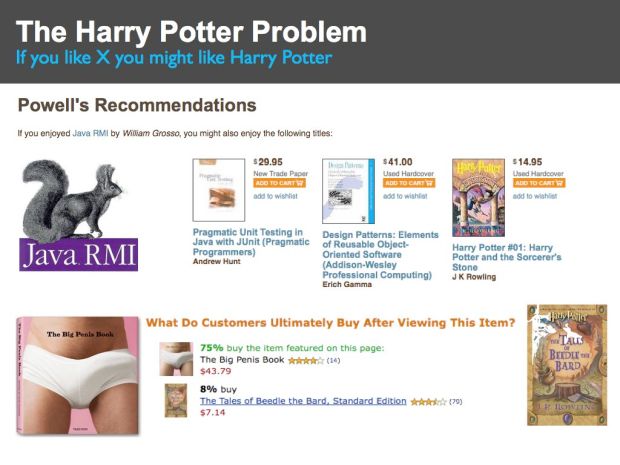

The Harry Potter Problem

This slide shows a recommendation “If you enjoy Java RMI” you many enjoy Harry Potter and the Sorcerers Stone”. Why is Harry Potter being recommended for a reader of a highly technical programming book?

Certain items, like the Harry Potter series of books, are very popular. This popularity can have an adverse affect on CF recommenders. Since popular items are purchased often they are frequently purchased with unrelated items. This can cause the recommender to associate the popular item with the unrelated item, as we see in this case. This effect is often called the Harry Potter effect. People who bought just about any book that you can think of, also bought a Harry Potter book.

Case in point is the “The Big Penis Book” – Amazon tells us that after viewing “The Big Penis Book” 8% of customers go on to by the Tales of Beedle the Bard from the Harry Potter series. It may be true that people who like big penises also like Harry Potter but it may not be the best recommendation.

(BTW, I often use examples from Amazon to highlight issues with recommendation. This doesn’t mean that Amazon has a bad recommender – in fact I think they have one of the best recommenders in the world. Whenever I go to Amazon to buy one book, I end up buying five because of their recommender. The issues that I show are not unique to the Amazon recommender. You’ll find the same issues with any other CF-based recommender.)

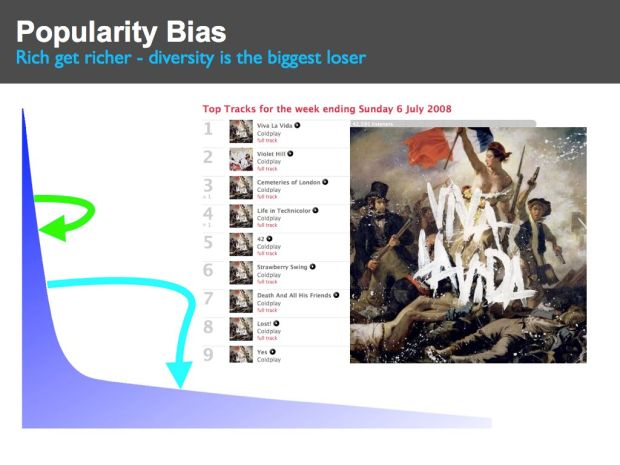

Popularity Bias

One effect of this Harry Potter problem is that a recommender will associate the popular item with many other items. The result is that the popular item tends to get recommended quite often and since it is recommended often, it is purchased often. This leads to a feedback loop where popular items get purchased often because they are recommended often and are recommended often because they are purchased often. This ‘rich-get-richer’ feedback loop leads to a system where popular items become extremely popular at the expense of the unpopular. The overall diversity of recommendations goes down. These feedback loops result in a recommender that pushes people toward more popular items and away from the long tail. This is exactly the opposite of what we are hoping that our recommenders will do. Instead of helping us find new and interesting music in the long tail, recommenders are pushing us back to the same set of very popular artists.

Note that you don’t need to have a fancy recommender system to be susceptible to these feedback loops. Even simple charts such as we see at music sites like the hype machine can lead to these feedback loops. People listen to tracks that are on the top of the charts, leading these songs to continue to be popular, and thus cementing their hold on the top spots in the charts.

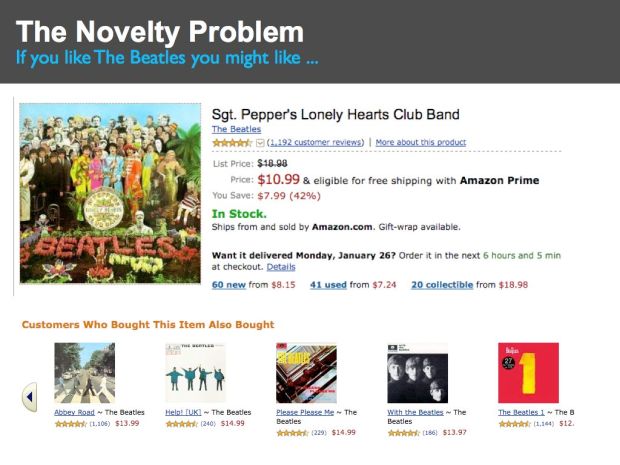

The Novelty Problem

There is a difference between a recommender that is designed for music discovery and one that is designed for music shopping. Most recommenders are intended to help a store make more money by selling you more things. This tends to lead to recommendations such as this one from Amazon – that suggests that since I’m interested in Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band that I might like Abbey Road and Please Please Me and every other Beatles album. Of course everyone in the world already knows about these items so these recommendations are not going to help people find new music. But that’s not the point, Amazon wants to sell more albums and recommending Beatles albums is a great way to do that.

One factor that is contributing to the Novelty Problem is high stakes evaluations like the Netflix prize. The Netflix prize is a competition that offers a million dollars to anyone that can improve the Netflix movie recommender by 10%. The evaluation is based on how well a recommender can predict how a movie viewer will rate a movie on a 1-5 star scale. This type of evaluation focuses on relevance – a recommender that can correctly predict that I’ll rate the movie ‘Titanic’ 2.2 stars instead of 2.0 stars – may score well in this type of evaluation, but that probably hasn’t really improved the quality of the recommendation. I won’t watch a 2.0 or a 2.2 star movie, so what does it matter. The downside of the Netflix prize is that only one metric – relevance – is being used to drive the advancement of recommender state-of-the-art when there are other equally import metrics – novelty is one of them.

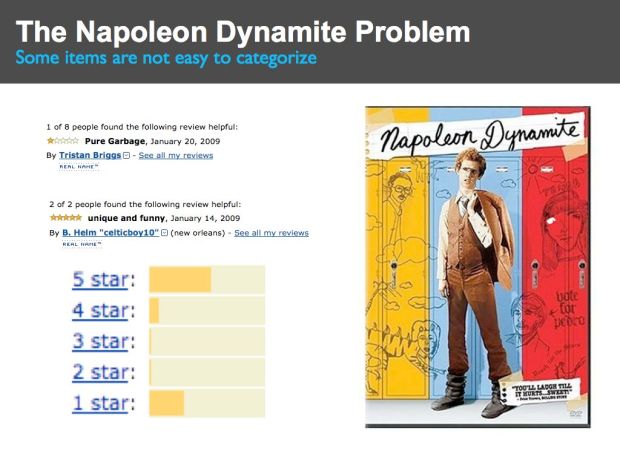

The Napoleon Dynamite Problem

Some items are not always so easy to categorize. For instance, if you look at the ratings for the movie Napoleon Dynamite you see a bimodal distribution of 5 stars and 1 stars. People either like it or hate it, and it is hard to predict how an individual will react.

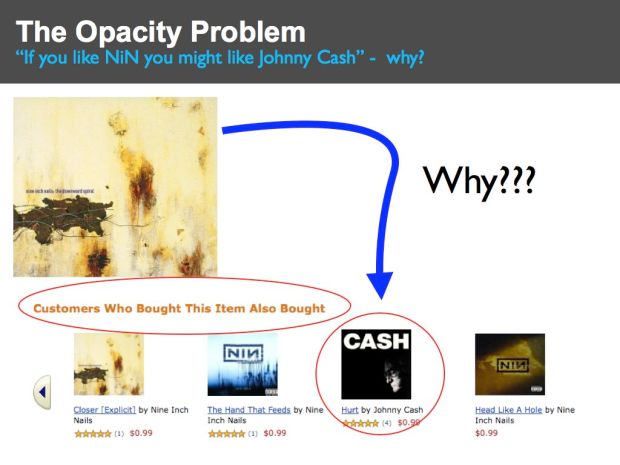

The Opacity Problem

Here’s an Amazon recommendation that suggests that if I like Nine Inch Nails that I might like Johnny Cash. Since NiN is an industrial band and Johnny Cash is a country/western singer, at first blush this seems like a bad recommendation, and if you didn’t know any better you may write this off as just another broken recommender. It would be really helpful if the CF recommender could explain why it is recommending Johnny Cash, but all it can really tell you is that ‘Other people who listened to NiN also listened to Johnny Cash’ which isn’t very helpful. If the recommender could give you a better explanation of why it was recommending something – perhaps something like “Johnny Cash has an absolutely stunning cover of the NiN song ‘hurt’ that will make you cry.” – then you would have a much better understanding of the recommendation. The explanation would turn what seems like a very bad recommendation into a phenomenal one – one that perhaps introduces you to whole new genre of music – a recommendation that may have you listening ‘Folsom Prison’ in a few weeks.

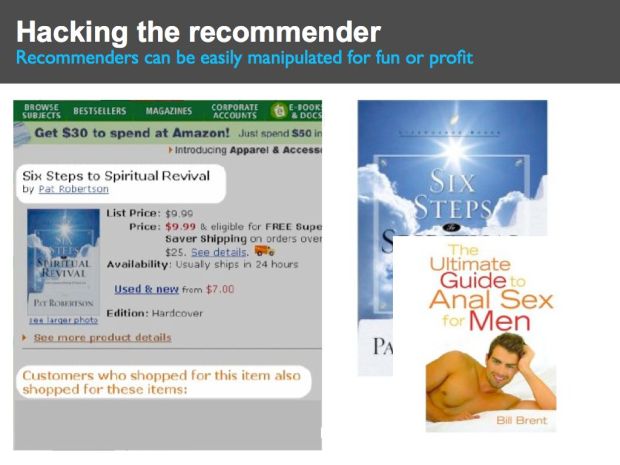

Hacking the Recommender

Here’s a recommendation based on a book by Pat Robertson called Six Steps to Spiritual Revival (courtesy of Bamshad Mobasher). This is a book by notorious televangelist Pat Roberston that promises to reveal “Gods’s Awesome Power in your life.” Amazon offers a recommendation suggesting that ‘Customers who shopped for this item also shopped for ‘The Ultimate Guide to Anal Sex for Men’. Clearly this is not a good recommendation. This bad recommendation is the result of a loosely organized group who didn’t like Pat Roberston, so they managed to trick the Amazon recommender into recommending a rather inappropriate book just by visiting the Amazon page for Robertson’s book and then visiting the Amazon page for the sex guide.

This manipulation of the Amazon recommender was easy to spot and can be classified as a prank, but it is not hard to image that an artist or a label may use similar techniques, but in a more subtle fashion to manipulate a recommender to promote their tracks (or to demote the competition). We already live in a world where search engine optimization is an industry. It won’t be long before recommender engine optimization will be an equally profitable (and destructive) industry.

Wrapping up

This is the first part of a two part post. In this post I’ve highlighted some of the issues in traditional music recommendation. Next post is all about how to fix these problems. For an alternative view be sure to visit Anthony Volodkin’s blog where he presents a rather different viewpoint about music recommendation.

Put a DONK on it

Posted by Paul in code, fun, Music, The Echo Nest on March 25, 2009

rfwatson has just released a site called donkdj that will ‘remix your favourite song into a bangin’ hard dance anthem‘. You upload a track and donkdj turns it into a dance remix. The results are just brilliant. Here are a few examples:

The site uses The Echo Nest Remix API to do all of the heavy lifting – adding a kick, snap, claps and the infamous donk (I had to look it up … a donk is a a pipe/plank-sound, that is used in Bouncy/scouse house/NRG music). What is doubly cool is rfwatson has open sourced his remix code so you can look under the hood and see how it works and adapt it for your own use. The core of this remix is done in just 200 lines of python code.

donkdj is really cool – the results sound fantastic and the open sourcing of the code makes it easy for anyone else to make their own remixer. I can’t wait to see it when someone makes an automatic Stephen Colbert remixer.

Update: Ben showed me this post that points to this video about Donk:

The full series is available here.

The Loudness War Analyzed

Posted by Paul in code, data, fun, Music, research, The Echo Nest, visualization on March 23, 2009

Recorded music doesn’t sound as good as it used to. Recordings sound muddy, clipped and lack punch. This is due to the ‘loudness war’ that has been taking place in recording studios. To make a track stand out from the rest of the pack, recording engineers have been turning up the volume on recorded music. Louder tracks grab the listener’s attention, and in this crowded music market, attention is important. And thus the loudness war – engineers must turn up the volume on their tracks lest the track sound wimpy when compared to all of the other loud tracks. However, there’s a downside to all this volume. Our music is compressed. The louds are louds and the softs are loud, with little difference. The result is that our music seems strained, there is little emotional range, and listening to loud all the time becomes tedious and tiring.

I’m interested in looking at the loudness for the recordings of a number of artists to see how wide-spread this loudness war really is. To do this I used the Echo Nest remix API and a bit of Python to collect and plot loudness for a set of recordings. I did two experiments. First I looked at the loudness for music by some of my favorite or well known artists. Then I looked at loudness over a large collection of music.

First, lets start with a loudness plot of Dave Brubeck’s Take Five. There’s a loudness range of -33 to about -15 dBs – a range of about 18 dBs.

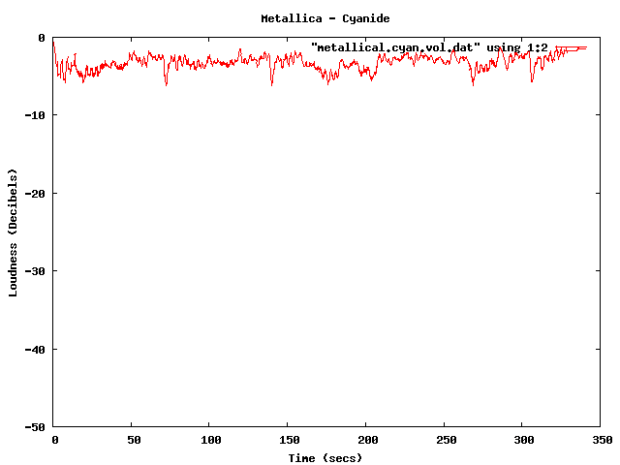

Now take a look at a track from the new Metallica album. Here we see a dB range of from about -3 dB to about -6 dB – for a range of about 3 dB. The difference is rather striking. You can see the lack of dynamic range in the plot quite easily.

Now you can’t really compare Dave Brubeck’s cool jazz with Metallica’s heavy metal – they are two very different kinds of music – so lets look at some others. (One caveat for all of these experiments – I don’t always know the provenance of all of my mp3s – some may be from remasters where the audio engineers may have adjusted the loudness, while some may be the original mix).

Here’s the venerable Stairway to Heaven – with a dB range of -40 dB to about -5dB for a range of 35 dB. That’s a whole lot of range.

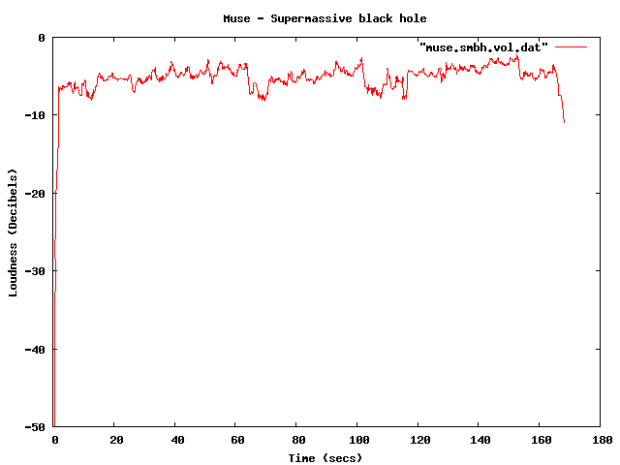

Compare that to the track ‘supermassive black hole’ – by Muse – with a range of just 4dB. I like Muse, but I find their tracks to get boring quickly – perhaps this is because of the lack of dynamic range robs some of the emotional impact. There’s no emotional arc like you can see in a song like Stairway to Heaven.

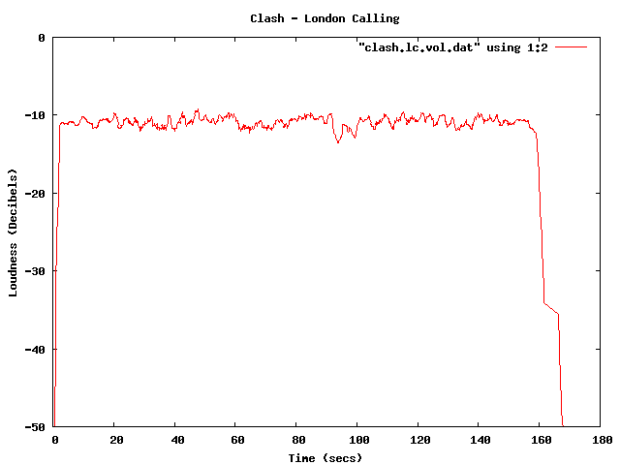

Some more examples – The Clash – London Calling. Not a wide dynamic range – but still not at ear splitting volumes.

This track by Nickleback is pushing the loudness envelope, but does have a bit of dynamic range.

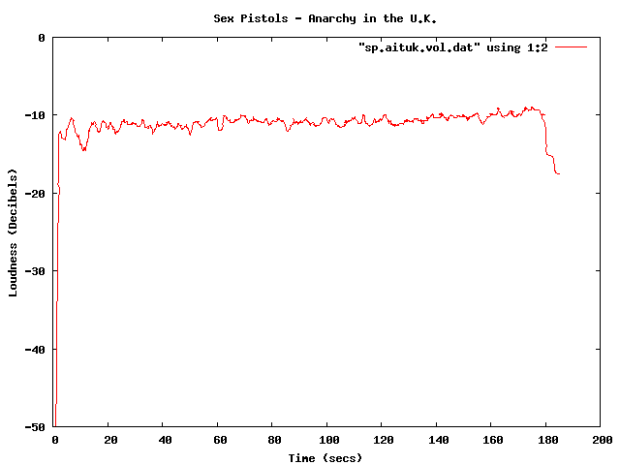

Compare the loudness level to the Sex Pistols. Less volume, and less dynamic range – but that’s how punk is – all one volume.

The Stooges – Raw Power is considered to be one of the loudest albums of all time. Indeed, the loudness curve is bursting through the margins of the plot.

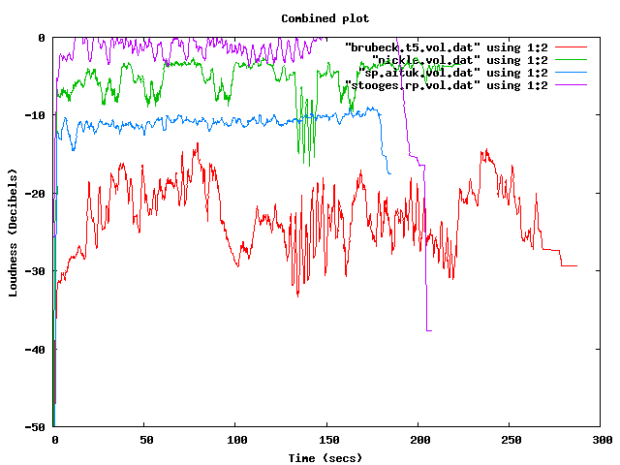

Here in one plot are 4 tracks overlayed – Red is Dave Brubeck, Blue is the Sex Pistols, Green is Nickleback and purple is the Stooges.

There been quite a bit of writing about the loudness war. The wikipedia entry is quite comprehensive, with some excellent plots showing how some recordings have had a loudness makeover when remastered. The Rolling Stone’s article: The Death of High Fidelity gives reactions of musicians and record producers to the loudness war. Producer Butch Vig says “Compression is a necessary evil. The artists I know want to sound competitive. You don’t want your track to sound quieter or wimpier by comparison. We’ve raised the bar and you can’t really step back.”

The loudest artists

I have analyzed the loudness of about 15K tracks from the top 1,000 or so most popular artists. The average loudness across all 15K tracks is about -9.5 dB. The very loudest artists from this set – those with a loudness of -5 dB or greater are:

| Artist | dB |

|---|---|

| Venetian Snares | -1.25 |

| Soulja Boy | -2.38 |

| Slipknot | -2.65 |

| Dimmu Borgir | -2.73 |

| Andrew W.K. | -3.15 |

| Queens of the Stone Age | -3.23 |

| Black Kids | -3.45 |

| Dropkick Murphys | -3.50 |

| All That Remains | -3.56 |

| Disturbed | -3.64 |

| Rise Against | -3.73 |

| Kid Rock | -3.86 |

| Amon Amarth | -3.88 |

| The Offspring | -3.89 |

| Avril Lavigne | -3.93 |

| MGMT | -3.94 |

| Fall Out Boy | -3.97 |

| Dragonforce | -4.02 |

| 30 Seconds To Mars | -4.08 |

| Billy Talent | -4.13 |

| Bad Religion | -4.13 |

| Metallica | -4.14 |

| Avenged Sevenfold | -4.23 |

| The Killers | -4.27 |

| Nightwish | -4.37 |

| Arctic Monkeys | -4.40 |

| Chromeo | -4.42 |

| Green Day | -4.43 |

| Oasis | -4.45 |

| The Strokes | -4.49 |

| System of a Down | -4.51 |

| Blink 182 | -4.52 |

| Bloc Party | -4.53 |

| Katy Perry | -4.76 |

| Barenaked Ladies | -4.76 |

| Breaking Benjamin | -4.80 |

| My Chemical Romance | -4.81 |

| 2Pac | -4.94 |

| Megadeth | -4.97 |

It is interesting to see that Avril Lavigne is louder than Metallica and Katy Perry is louder than Megadeth.

The Quietest Artists

Here are the quietest artists:

| Artist | dB |

|---|---|

| Brian Eno | -17.52 |

| Leonard Cohen | -16.24 |

| Norah Jones | -15.75 |

| Tori Amos | -15.23 |

| Jeff Buckley | -15.21 |

| Neil Young | -14.51 |

| Damien Rice | -14.33 |

| Lou Reed | -14.33 |

| Cat Stevens | -14.22 |

| Bon Iver | -14.14 |

| Enya | -14.13 |

| The Velvet Underground | -14.05 |

| Simon & Garfunkel | -14.03 |

| Pink Floyd | -13.96 |

| Ben Harper | -13.94 |

| Aphex Twin | -13.93 |

| Grateful Dead | -13.85 |

| James Taylor | -13.81 |

| The Very Hush Hush | -13.73 |

| Phish | -13.71 |

| The National | -13.57 |

| Paul Simon | -13.53 |

| Sufjan Stevens | -13.41 |

| Tom Waits | -13.33 |

| Elvis Presley | -13.21 |

| Elliott Smith | -13.06 |

| Celine Dion | -12.97 |

| John Lennon | -12.92 |

| Bright Eyes | -12.92 |

| The Smashing Pumpkins | -12.83 |

| Fleetwood Mac | -12.82 |

| Tool | -12.62 |

| Frank Sinatra | -12.59 |

| A Tribe Called Quest | -12.52 |

| Phil Collins | -12.27 |

| 10,000 Maniacs | -12.04 |

| The Police | -12.02 |

| Bob Dylan | -12.00 |

(note that I’m not including classical artists that tend to dominate the quiet side of the spectrum)

Again, there are caveats with this analysis. Many of the recordings analyzed may be remastered versions that have have had their loudness changed from the original. A proper analysis would be to repeat using recordings where the provenance is well known. There’s an excellent graphic in the wikipedia that shows the effect that remastering has had on 4 releases of a Beatles track.

Loudness as a function of Year

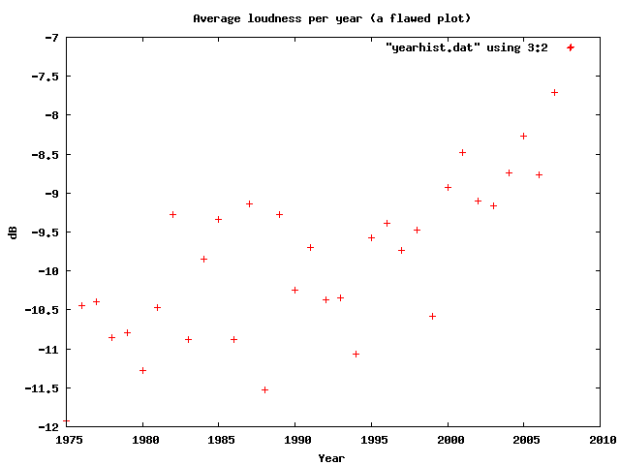

Here’s a plot of the loudness as a function of the year of release of a recording (the provenance caveat applies here too). This shows how loudness has increased over the last 40 years

I suspect that re-releases and re-masterings are affecting the Loudness averages for years before 1995. Another experiment is needed to sort that all out.

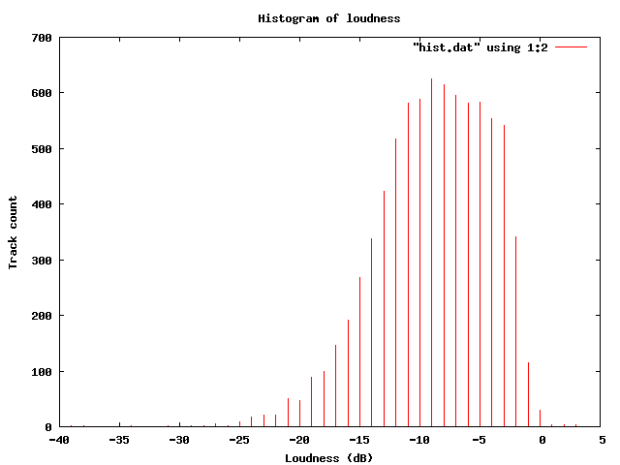

Loudness Histogram:

This table shows the histogram of Loudness:

Average Loudness per genre

This table shows the average loudness as a function of genre. No surprise here, Hip Hop and Rock is loud, while Children’s and Classical is soft:

| Genre | dB |

|---|---|

| Hip Hop | -8.38 |

| Rock | -8.50 |

| Latin | -9.08 |

| Electronic | -9.33 |

| Pop | -9.60 |

| Reggae | -9.64 |

| Funk / Soul | -9.83 |

| Blues | -9.86 |

| Jazz | -11.20 |

| Folk, World, & Country | -11.32 |

| Stage & Screen | -14.29 |

| Classical | -16.63 |

| Children’s | -17.03 |

So, why do we care? Why shouldn’t our music be at maximum loudness? This Youtube video makes it clear:

Luckily, there are enough people that care about this to affect some change. The organization Turn Me Up! is devoted to bringing dynamic range back to music. Turn Me Up! is a non-profit music industry organization working together with a group of highly respected artists and recording professionals to give artists back the choice to release more dynamic records.

Luckily, there are enough people that care about this to affect some change. The organization Turn Me Up! is devoted to bringing dynamic range back to music. Turn Me Up! is a non-profit music industry organization working together with a group of highly respected artists and recording professionals to give artists back the choice to release more dynamic records.

If I had a choice between a loud album and a dynamic one, I’d certainly go for the dynamic one.

Update: Andy exhorts me to make code samples available – which, of course, is a no-brainer – so here ya go: volume.py

Help! My iPod thinks I’m emo.

Posted by Paul in Music, recommendation, research, The Echo Nest on March 23, 2009

Here are the slides for the panel “Help! My iPod thinks I’m emo.” that Anthony Volodkin (from The Hype Machine) and I gave at SXSW on music recommendation:

More on click tracks …

Posted by Paul in fun, Music, The Echo Nest on March 9, 2009

I’ve just been astounded by the number of and quality of the comments that I’ve received on my recent ‘searching for click track’ posts. I’ve learned a lot about modern music production, drumming, the power of Waxy, Slashdot, Reddit, Stumbleupon, Metafilter and BoingBoing and a bit more about python. I was surprised and heartened by the fact that even those who thought I was wrong, or thought that my analysis was off beat (snicker), offered their criticism in a very civil fashion – is this really the Internet?

Many have suggested other drummers to analyze and I’ve taken a quick look at some but I haven’t had time to do anything (I’ve got this SXSW talk to prepare, plus my regular job to do as well, sigh). Luckily enough, some others have already started to do some analyses. I shall try to post the analysis that people add to the comments or send to me here, so we can build a nice directory of click plots for various drummers.

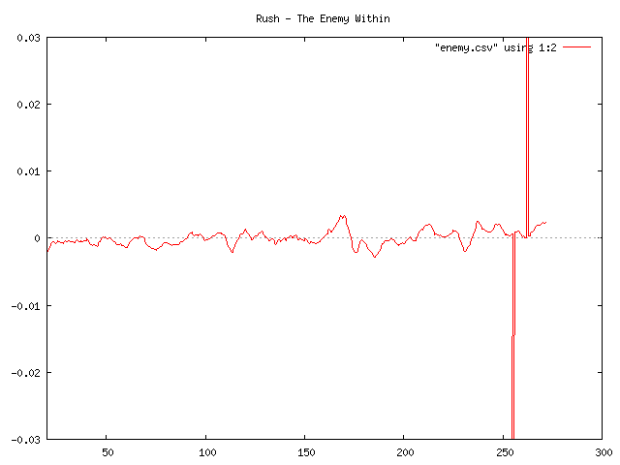

Rush – The Enemy Within

Plot by Arren Lex

It looks to me like Neil Pert is using a click track on this song.

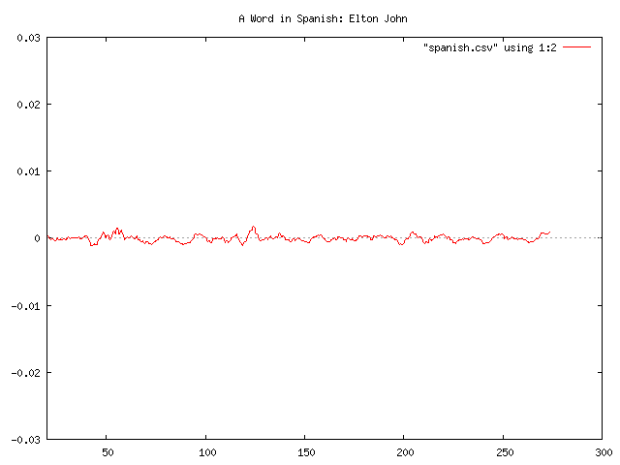

Elton John – A word in spanish

Plot by Arren Lex

Looks like a click track

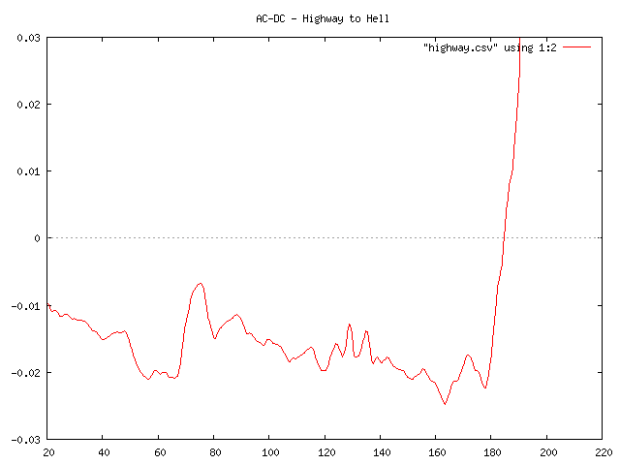

AC / DC – Highway to hell

Plot by Arren Lex

Looks like no click track for Phil Rudd.

In search of the click track

Posted by Paul in code, fun, Music, The Echo Nest on March 2, 2009

Sometime in the last 10 or 20 years, rock drumming has changed. Many drummers will now don headphones in the studio (and sometimes even for live performances) and synchronize their playing to an electronic metronome – the click track. This allows for easier digital editing of the recording. Since all of the measures are of equal duration, it is easy to move measures or phrases around without worry that the timing may be off. The click track has a down side – some say that songs recorded against a click track sound sterile, that the missing tempo deviations added life to a song.

I’ve always been curious about which drummers use a click track and which don’t, so I thought it might be fun to try to build a click track detector using the Echo Nest remix SDK ( remix is a Python library that allows you to analyze and manipulate music). In my first attempt, I used remix to analyze a track and then I just printed out the duration of each beat in a song and used gnuplot to plot the data. The results weren’t so good – the plot was rather noisy. It turns out there’s quite a bit of variation from beat to beat. In my second attempt I averaged the beat durations over a short window, and the resulting plot was quite good.

Now to see if we can use the plots as a click track detector. I started with a track where I knew the drummer didn’t use a click track. I’m pretty sure that Ringo never used one – so I started with the old Beatle’s track – Dizzy Miss Lizzie. Here’s the resulting plot:

This plot shows the beat duration variation (in seconds) from the average beat duration over the course of about two minutes of the song (I trimmed off the first 10 seconds, since many songs take a few seconds to get going). In this plot you can clearly see the beat duration vary over time. The 3 dips at about 90, 110 and 130 correspond to the end of a 12 bar verse, where Ringo would slightly speed up.

This plot shows the beat duration variation (in seconds) from the average beat duration over the course of about two minutes of the song (I trimmed off the first 10 seconds, since many songs take a few seconds to get going). In this plot you can clearly see the beat duration vary over time. The 3 dips at about 90, 110 and 130 correspond to the end of a 12 bar verse, where Ringo would slightly speed up.

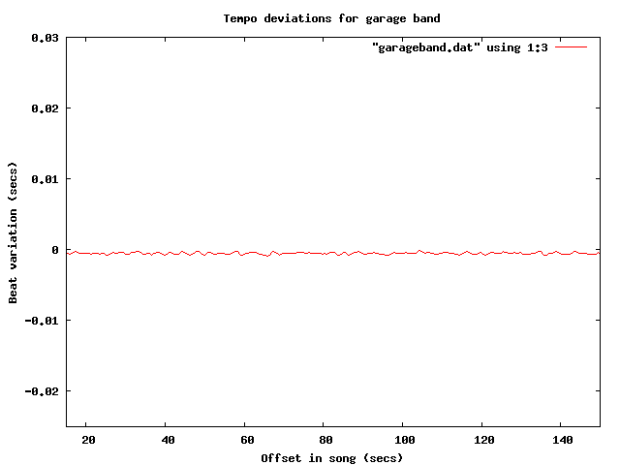

Now lets compare this to a computer generated drum track. I created a track in GarageBand with a looping drum and ran the same analysis. Here’s the resulting plot:

The difference is quite obvious, and stark. The computer gives a nice steady, sterile beat, compared to Ringo’s.

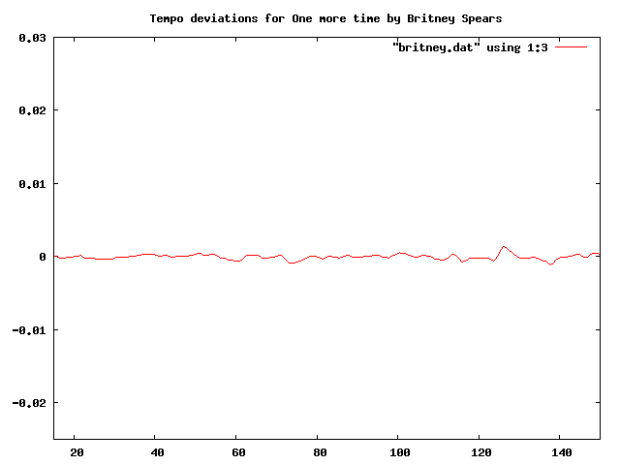

Now let’s try some real music that we suspect is recorded to a click track. It seems that most pop music nowadays is overproduced, so my suspicion is that an artist like Britney Spears will record against a click track. I ran the analysis on “Hit me baby one more time” (believe it or not, the song was not in my collection, so I had to go and find it on the internet, did you know that it is pretty easy to find music on the internet?). Here’s the plot:

I think it is pretty clear from the plot that “Hit me baby one more time” was recorded with a click track. And it is pretty clear that these plots make a pretty good click track detector. Flat lines correspond to tracks with little variation in beat duration. So lets explore some artists to see if they use click tracks.

First up: Weezer:

Nope, no click track for Weezer. This was a bit of a surprise for me.

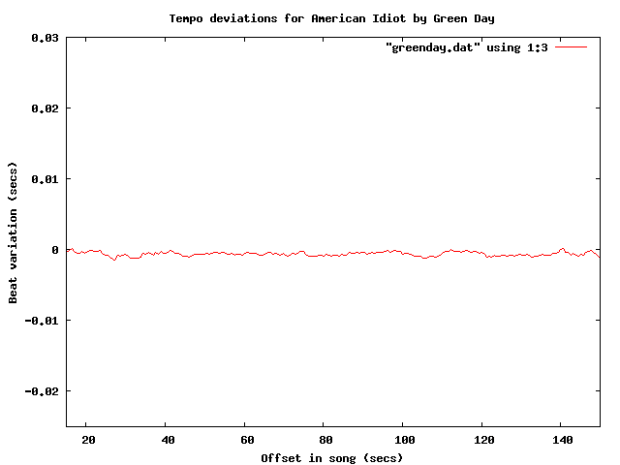

How about Green Day?

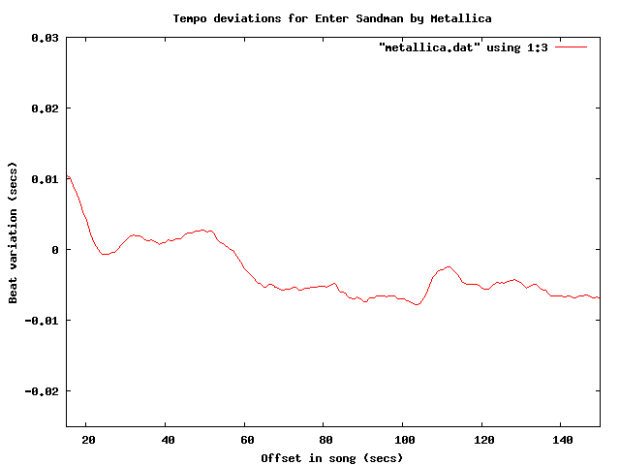

Yep – clearly a click track there. How about Metallica?

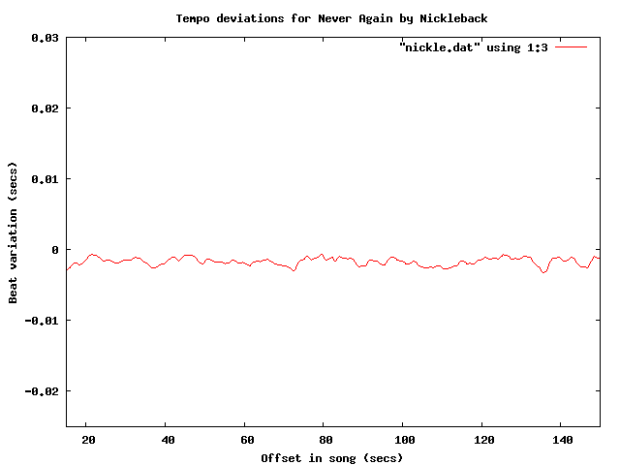

No click track for Lars! Nickeback?

update: fixed nickleback plot labels (thanks tedder)

update: fixed nickleback plot labels (thanks tedder)

No surprise there – Nickleback uses a click track. Another numetal band (one that I rather like alot) is Breaking Benjamin:

It is clear that they use a click track too – but what is interesting here is that you can see the bridge – the hump that starts at about 130 seconds into the song.

It is clear that they use a click track too – but what is interesting here is that you can see the bridge – the hump that starts at about 130 seconds into the song.

Of course John Bonham never used a click track – but lets check for fun:

So there you have it, using the Echo Nest remix SDK, gnuplot and some human analysis of the generated plots it is pretty easy to see which tracks are recorded against a click track. To make it really clear, I’ve overlayed a few of the plots:

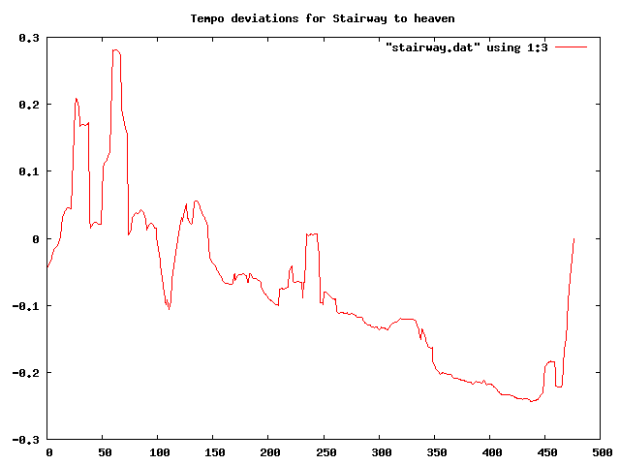

One final plot … the venerable stairway to heaven is noted for its gradual increase in intensity – part of that is from the volume and part comes from in increase in tempo. Jimmy Page stated that the song “speeds up like an adrenaline flow”. Let’s see if we can see this:

The steady downward slope shows shorter beat durations over the course of the song (meaning a faster song). That’s something you just can’t do with a click track. Update – as a number of commenters have pointed out, yes you can do this with a click track.

The code to generate the data for the plots is very simple:

def main(inputFile):

audiofile = audio.LocalAudioFile(inputFile)

beats = audiofile.analysis.beats

avgList = []

time = 0;

output = []

sum = 0

for beat in beats:

time += beat.duration

avg = runningAverage(avgList, beat.duration)

sum += avg

output.append((time, avg))

base = sum / len(output)

for d in output:

print d[0], d[1] - base

def runningAverage(list, dur):

max = 16

list.append(dur)

if len(list) > max:

list.pop(0)

return sum(list) / len(list)

I’m still a poor python programmer, so no doubt there are better Pythonic ways to do things – so let me know how to improve my Python code.

If any readers are particularly curious about whether an artist uses a click track let me know and I’ll generate the plots – or better yet, just get your own API key and run the code for yourself.

Update: If you live in the NYC area, and want to see/hear some more about remix, you might want to attend dorkbot-nyc tomorrow (Wednesday, March 4) where Brian will be talking about and demoing remix.

Update – Sten wondered (in the comments) how his band Hungry Fathers would plot given that their drummer uses a click track. Here’s an analysis of their crowd pleaser “A day without orange juice” that seems to indicate that they do indeed use a click track:

Update: More reader contributed click plots are here: More on click tracks ….

Update 2: I’ve written an application that lets you generate your own interactive click plots: The Echo Nest BPM Explorer

sched.org support added to SXSW Artist Catalog

Posted by Paul in search, The Echo Nest on March 1, 2009

I’ve just pushed out a new version of my SXSW Artist Catalog that lets you add any artist to your SXSW schedule (via sched.org). Each artist now has a ‘schedule at sched.org’ link which brings you directly to the sched.org page for the artist where you can select the artist event that you are interested in and then add it to your schedule. It is pretty handy.

By the way, the integration with sched.org could not have been easier. Taylor McKnight added a search url of the form:

http://sxsw2009.sched.org/?searchword=DEVO

that brings you to the DEVO page at sched.org. Very nice.

While adding the sched support, I also did a recrawl of all the artist info, so the data should be pretty fresh.

Thanks to Steve for fixing things for me after I had botched things up on the deploy, and thanks in general to Sun for continuing to host the catalog.

By the way, doing this update was a bit of a nightmare. The key data for the guide is the artist list that is crawled from the SXSW site – but the SXSW folks have recently changed the format of the artist list (spreading it out over multiple pages, adding more context, etc ). I didn’t want to have to rewrite the parsing code (when working on a spare time project, just the thought of working with regular expressions makes me close the IDE and fire up Team Fortress 2). Luckily, I had anticipated this event – my SXSW crawler had diligently been creating archives of every SXSW crawl, so if they did change formats, I could fall back on a previous crawl without needing to work on the parser. I’m so smart. Except that I had a bug. Here’s the archive code:

public void createArchive(URL url) throws IOException {

createArchiveDir();

File file = new File(getArchiveName());

if (!file.exists()) {

URLConnection connection = url.openConnection();

BufferedReader in = new BufferedReader(

newInputStreamReader(connection.getInputStream()));

PrintWriter out = new PrintWriter(getArchiveName());

String line = null;

try {

while ((line = in.readLine()) != null) {

out.println(line);

}

} finally {

in.close();

}

}

See the bug? Yep, I forgot to close the output file – which means that all of my many archive files were missing the last block of data, making them useless. My pennance for this code-and-test sin was that I had to go and rewrite the SXSW parser to support the new format. But this turned out to be a good thing, since SXSW has been adding more artists. So this push has a new fresh crawl, with the absolute latest artists, fresh data from all of the sites like Youtube, Flicker, Last.fm and The Echo Nest. My bug makes more work for me, but a better catalog for you.

The Echo Nest Remix SDK

Posted by Paul in fun, Music, The Echo Nest on February 28, 2009

One of the joys of working at the Echo Nest is the communal music playlist. Anyone can add, rearrange or delete music from the queue. Of course, if you need to bail out (like when that Cindi Lauper track is sending you over the edge) you can always put on your headphones and tune out the mix. The other day, George Harrison’s “Here Comes the Sun” started playing, but this was a new version – with a funky drum beat, that I had never heard before – perhaps this was a lost track from the Beatle’s Love? Nope, turns out it was just Ben, one of the Echo Nest developers, playing around with The Echo Nest Remix SDK.

The Echo Nest Remix SDK is an open source Python library that lets you manipulate music and video. It sits on top of the Echo Nest Analyze API, hides all of the messy details of sending audio back to the Echo Nest, and parsing the XML response, while still giving you access to the full power of the API.

remix – is one of The Echo Nest’s secret weapons – it gives you the ability to analyze and manipulate music – and not just audio manipulations such as filtering or equalizing, but the ability to remix based on the hierarchical structure of a song. remix sits on top of a very deep analysis of the music that teases out all sorts of information about a track. There’s high level information such as the key, tempo time signature, mode (major or minor) and overall loudness. There’s also information about the song structure. A song is broken down into sections (think verse, chorus, bridge, solo), bars, beats, tatums (the smallest perceptual metrical unit of the song) and segments (short, uniform sound entities). remix gives you access to all of this information.

I must admit that I’ve been a bit reluctant to use remix – mainly because after 9 years at Sun Microsystems I’m a hard core Java programmer (the main reason I went to Sun in the first place was because I liked Java so much). Every time I start to use Python I get frustrated because it takes me 10 times longer than it would in Java. I have to look everything up. How do I concatenate strings? How do I find the length of a list? How do I walk a directory tree? I can code so much faster in Java. But … if there was ever a reason for me to learn Python it is this remix SDK. It is just so much fun – and it lets you do some of the most incredible things. For example, if you want to add a cowbell to every beat in a song, you can use remix to get the list of all of the beats (and associated confidences) in a song, and simply overlap a cowbell strike at each of the time offsets.

So here’s my first bit of Python code using remix. I grabbed one of the code samples that’s included in the distribution, had the aforementioned Ben spend two minutes walking me through the subtleties of Audio Quantum and I was good to go. My first bit of code just takes a song and swaps beat two and beat three of all measures that have at least 3 beats.

def swap_beat_2_and_3(inputFile, outputFile):

audiofile = audio.LocalAudioFile(inputFile)

bars = audiofile.analysis.bars

collect = audio.AudioQuantumList()

for bar in bars:

beats = bar.children()

if (len(beats) >= 3):

(beats[1], beats[2]) = (beats[2], beats[1])

for beat in beats:

collect.append(beat);

out = audio.getpieces(audiofile, collect)

out.encode(outputFile)

The code analyzes the input, iterates through the bars and if a bar has more than three beats, swaps them. (I must admit, even as a hard core Java programmer, the ability to swap things with (a,b) = (b,a) is pretty awesome) and then encodes and writes out a new audiofile. The resulting audio is surprisingly musical. Here’s the result as applied to Maynard Ferguson’s “Birdland”:

This is just great programming fun. I think I’ll be spending my spare coding time learning more Python so I can explore all of the things one can do with remix.