Archive for category data

TagatuneJam

Posted by Paul in data, Music, music information retrieval, research on April 28, 2009

TagATune, the music-oriented ‘game with a purpose’ is now serving music from Jamendo.com. TagATune has already been an excellent source of high quality music labels. Now they will be getting gamers to apply music labels to popular music. A new dataset will be forthcoming. Also, adding to the excitement of this release, is the announcment of a contest. The highest scoring Jammer will be formally acknowledged as a contributor to this dataset as well as receive a special mytery prize. (I think it might be jam). Sweet.

TagATune, the music-oriented ‘game with a purpose’ is now serving music from Jamendo.com. TagATune has already been an excellent source of high quality music labels. Now they will be getting gamers to apply music labels to popular music. A new dataset will be forthcoming. Also, adding to the excitement of this release, is the announcment of a contest. The highest scoring Jammer will be formally acknowledged as a contributor to this dataset as well as receive a special mytery prize. (I think it might be jam). Sweet.

libre.fm – what’s the point?

Posted by Paul in code, data, Music, recommendation, web services on April 24, 2009

Libre.fm is essentially an open source clone of Last.fm’s audioscrobbler. With Libre.fm you can scrobble your music play behavior to a central server, where your data is aggregated with all of the other scrobbles and can be used to create charts, recommendations, playlists – all the sorts of things we see at Last.fm. As the name implies, everything about Libre.fm is free. All the Libre.fm code is released under the GNU AGPL. You can run your own server. You own your own data.

Libre.fm is essentially an open source clone of Last.fm’s audioscrobbler. With Libre.fm you can scrobble your music play behavior to a central server, where your data is aggregated with all of the other scrobbles and can be used to create charts, recommendations, playlists – all the sorts of things we see at Last.fm. As the name implies, everything about Libre.fm is free. All the Libre.fm code is released under the GNU AGPL. You can run your own server. You own your own data.

The Libre project is just getting underway. Not only is paint is not dry, they’ve only just put down the drop cloth, got the brushes ready and opened the can. Right now there’s a minimal scrobbler server (called GNUkebox) that will take anyone’s scrobbles and adds them to a postgres database. This server is compatible with Last.fm’s so nearly all scrobbling clients will scrobble to Libre.fm. (Note that to get many clients to work you actually have to modify your /etc/hosts file to redirect outgoing connections that would normally go to post.audioscrobbler.com so that they go to the libre.fm scrobbling machine. It is a clever way to get instant support for Libre.fm by lots of clients, but I must admit I feel a bit dirty lying to my computer about where to send the scrobbles.)

Another component of Libre.fm is the web front end (called nixtape) that shows what people are playing, what is popular, artist charts and clouds. (Imagine what Audioscrobbler.com looked like in 2005). Here’s my Libre.fm page:

There is already quite a lot of functionality on the web front end – there are (at least minimal) user, artist, album and track pages. However, there are some critical missing bits – perhaps most significant of these is the lack of a recommender. The only discovery tool so far at Libre.fm is the clickable ‘Explore popular artist’ cloud:

There is already quite a lot of functionality on the web front end – there are (at least minimal) user, artist, album and track pages. However, there are some critical missing bits – perhaps most significant of these is the lack of a recommender. The only discovery tool so far at Libre.fm is the clickable ‘Explore popular artist’ cloud:

Libre.fm has only been live for a few week – but it is already closing in on its millionth scrobble. As I write this, about 340K tracks have been scrobbled by 2011 users with a total of 920052 plays. (Note that since Libre.fm lets you import your Last.fm listening history, many of these plays have been previously scrobbled at Last.fm).

When you compare these numbers to Last.fm’s, Libre.fm’s numbers are very small – but if you consider the very short time that it has been live, these numbers start to look pretty good. What is even more important is that Libre.fm has already built a core team of over two dozen developers. Two dozen developers can write a crazy amount of code in a short time – so I’m expecting to see the gaps in Libre.fm functionality to be filled rather quickly. And as the gaps in functionality are eliminated, more users will come (especially those users who’ve recently abandoned Last.fm when Last.fm started to charge users that don’t live in the U.S., U.K. or Germany).

I remember way back in 1985 reading this article in Byte magazine about this seemingly crazy guy named Richard Stallman who was creating his own operating system called GNU. I couldn’t understand why he was doing it. We already had MS-DOS and Unix (I was using DEC’s Ultrix at the time which was a mighty fine OS). I didn’t think we needed anything else. But Stallman was on a mission – that mission was to create free software. Software that you were free to run, free to modify, free to distribute. I was wrong about Stallman. His set of tools became key parts of Linux and his ideas about ‘CopyLeft’ enabled the open source movement.

When I first heard about Libre.fm, my reaction was very similar to my reaction back in 1985 to Stallman – what’s the point? Last.fm already provides all these services and much more. Last.fm lets you get access to your data via their web services. Last.fm already has billions of scrobbles from millions of users. Why do we need another Last.fm? But this time I’m prepared to be wrong. Perhaps we don’t really want our data held by one company. Perhaps a community of passionate developers can take the core concept of the audioscrobbler to somewhere new. Just as Stallman’s crazy idea has changed the way we think about developing software, perhaps Libre.fm is the begining of the next revolution in music discovery.

Update – I asked mattl, founder of libre.fm, what his motivation for creating libre.fm is. He says there are two prime motivations:

- Artistic – “I wants to support libre musicians. To give them a platform where they are the ruling class.”

- freedom – “give everyone access to their data, so even if they don’t like what we’re doing with libre music, the software is still free (to them and us)”

Removing accents in artist names

Posted by Paul in code, data, java, Music, The Echo Nest, web services on April 10, 2009

If you write software for music applications, then you understand the difficulties in dealing with matching artist names. There are lots of issues: spelling errors, stop words (‘the beatles’ vs. ‘beatles, the’ vs ‘beatles’), punctuation (is it “Emerson, Lake and Palmer” or “Emerson, Lake & Palmer“), common aliases (ELP, GNR, CSNY, Zep), to name just a few of the issues. One common problem is dealing with international characters. Most Americans don’t know how to type accented characters on their keyboards so when they are looking for Beyoncé they will type ‘beyonce’. If you want your application to find the proper artist for these queries you are going to have deal with these missing accents in the query. One way to do this is to extend the artist name matching to include a check against a version of the artist name where all of the accents have been removed. However, this is not so easy to do – You could certainly build a mapping table of all the possible accented characters, but that is prone to failure. You may neglect some obscure character mapping (like that funny ř in Antonín Dvořák).

Luckily, in Java 1.6 there’s a pretty reliable way to do this. Java 1.6 added a Normalizer class to the java. text package. The Normalize class allows you to apply Unicode Normalization to strings. In particular you can apply Unicode decomposition that will replace any precomposed character into a base character and the combining accent. Once you do this, its a simple string replace to get rid of the accents. Here’s a bit of code to remove accents:

public static String removeAccents(String text) {

return Normalizer.normalize(text, Normalizer.Form.NFD)

.replaceAll("\\p{InCombiningDiacriticalMarks}+", "");

}

This is nice and straightforward code, and has no effect on strings that have no accents.

Of course ‘removeAccents’ doesn’t solve all of the problems – it certainly won’t help you deal with artist names like ‘KoЯn’ nor will it deal with the wide range of artist name misspellings. If you are trying to deal normalizing aritist names you should read how Columbia researcher Dan Ellis has approached the problem. I suspect that someday, (soon, I hope) there will be a magic music web service that will solve this problem once and for all and you”ll never again have to scratch our head at why you are listening to a song by Peter, Bjork and John, instead of a song by Björk.

Magnatagatune – a new research data set for MIR

Posted by Paul in data, Music, music information retrieval, research, tags, The Echo Nest on April 1, 2009

Edith Law (of TagATune fame) and Olivier Gillet have put together one of the most complete MIR research datasets since uspop2002. The data (with the best name ever) is called magnatagatune. It contains:

- Human annotations collected by Edith Law’s TagATune game.

- The corresponding sound clips from magnatune.com, encoded in 16 kHz, 32kbps, mono mp3. (generously contributed by John Buckman, the founder of every MIR researcher’s favorite label Magnatune)

- A detailed analysis from The Echo Nest of the track’s structure and musical content, including rhythm, pitch and timbre.

- All the source code for generating the dataset distribution

Some detailed stats of the data calculated by Olivier are:

- clips: 25863

- source mp3: 5405

- albums: 446

- artists: 230

- unique tags: 188

- similarity triples: 533

- votes for the similarity judgments: 7650

This dataset is one stop shopping for all sorts of MIR related tasks including:

- Artist Identification

- Genre classification

- Mood Classification

- Instrument identification

- Music Similarity

- Autotagging

- Automatic playlist generation

As part of the dataset The Echo Nest is providing a detailed analysis of each of the 25,000+ clips. This analysis includes a description of all musical events, structures and global attributes, such as key, loudness, time signature, tempo, beats, sections, and harmony. This is the same information that is provided by our track level API that is described here: developer.echonest.com.

Note that Olivier and Edith mention me by name in their release announcement, but really I was just the go between. Tristan (one of the co-founders of The Echo Nest) did the analysis and The Echo Nest compute infrastructure got it done fast (our analysis of the 25,000 tracks took much less time than it did to download the audio).

I expect to see this dataset become one of the oft-cited datasets of MIR researchers.

Here’s the official announcement:

Edith Law, John Buckman, Paul Lamere and myself are proud to announce the release of the Magnatagatune dataset.

This dataset consists of ~25000 29s long music clips, each of them annotated with a combination of 188 tags. The annotations have been collected through Edith’s “TagATune” game (http://www.gwap.com/gwap/gamesPreview/tagatune/). The clips are excerpts of songs published by Magnatune.com – and John from Magnatune has approved the release of the audio clips for research purposes. For those of you who are not happy with the quality of the clips (mono, 16 kHz, 32kbps), we also provide scripts to fetch the mp3s and cut them to recreate the collection. Wait… there’s more! Paul Lamere from The Echo Nest has provided, for each of these songs, an “analysis” XML file containing timbre, rhythm and harmonic-content related features.

The dataset also contains a smaller set of annotations for music similarity: given a triple of songs (A, B, C), how many players have flagged the song A, B or C as most different from the others.

Everything is distributed freely under a Creative Commons Attribution – Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 license ; and is available here: http://tagatune.org/Datasets.html

This dataset is ever-growing, as more users play TagATune, more annotations will be collected, and new snapshots of the data will be released in the future. A new version of TagATune will indeed be up by next Monday (April 6). To make this dataset grow even faster, please go to http://www.gwap.com/gwap/gamesPreview/tagatune/ next Monday and start playing.

Enjoy!

The Magnatagatune team

The Loudness War Analyzed

Posted by Paul in code, data, fun, Music, research, The Echo Nest, visualization on March 23, 2009

Recorded music doesn’t sound as good as it used to. Recordings sound muddy, clipped and lack punch. This is due to the ‘loudness war’ that has been taking place in recording studios. To make a track stand out from the rest of the pack, recording engineers have been turning up the volume on recorded music. Louder tracks grab the listener’s attention, and in this crowded music market, attention is important. And thus the loudness war – engineers must turn up the volume on their tracks lest the track sound wimpy when compared to all of the other loud tracks. However, there’s a downside to all this volume. Our music is compressed. The louds are louds and the softs are loud, with little difference. The result is that our music seems strained, there is little emotional range, and listening to loud all the time becomes tedious and tiring.

I’m interested in looking at the loudness for the recordings of a number of artists to see how wide-spread this loudness war really is. To do this I used the Echo Nest remix API and a bit of Python to collect and plot loudness for a set of recordings. I did two experiments. First I looked at the loudness for music by some of my favorite or well known artists. Then I looked at loudness over a large collection of music.

First, lets start with a loudness plot of Dave Brubeck’s Take Five. There’s a loudness range of -33 to about -15 dBs – a range of about 18 dBs.

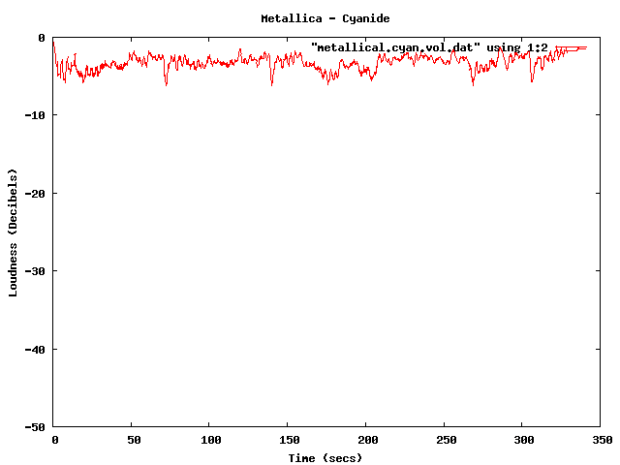

Now take a look at a track from the new Metallica album. Here we see a dB range of from about -3 dB to about -6 dB – for a range of about 3 dB. The difference is rather striking. You can see the lack of dynamic range in the plot quite easily.

Now you can’t really compare Dave Brubeck’s cool jazz with Metallica’s heavy metal – they are two very different kinds of music – so lets look at some others. (One caveat for all of these experiments – I don’t always know the provenance of all of my mp3s – some may be from remasters where the audio engineers may have adjusted the loudness, while some may be the original mix).

Here’s the venerable Stairway to Heaven – with a dB range of -40 dB to about -5dB for a range of 35 dB. That’s a whole lot of range.

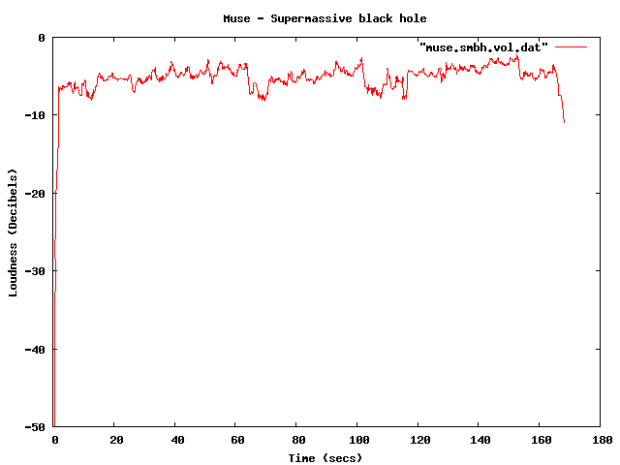

Compare that to the track ‘supermassive black hole’ – by Muse – with a range of just 4dB. I like Muse, but I find their tracks to get boring quickly – perhaps this is because of the lack of dynamic range robs some of the emotional impact. There’s no emotional arc like you can see in a song like Stairway to Heaven.

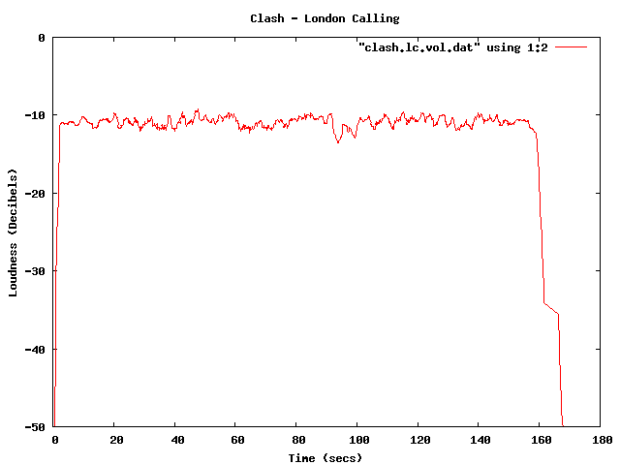

Some more examples – The Clash – London Calling. Not a wide dynamic range – but still not at ear splitting volumes.

This track by Nickleback is pushing the loudness envelope, but does have a bit of dynamic range.

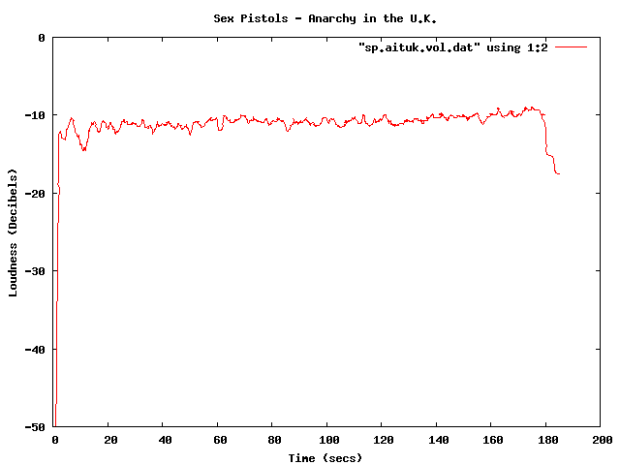

Compare the loudness level to the Sex Pistols. Less volume, and less dynamic range – but that’s how punk is – all one volume.

The Stooges – Raw Power is considered to be one of the loudest albums of all time. Indeed, the loudness curve is bursting through the margins of the plot.

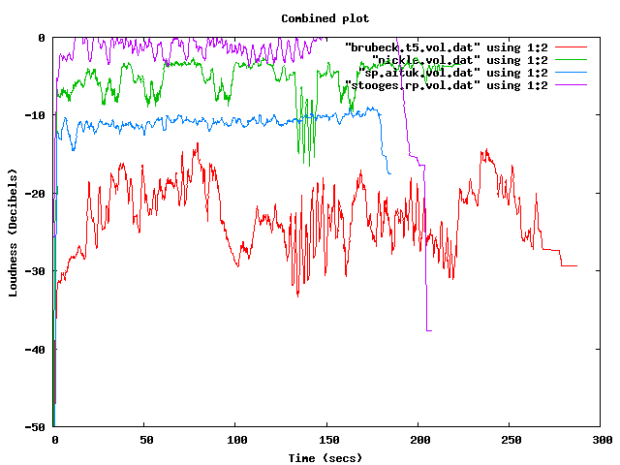

Here in one plot are 4 tracks overlayed – Red is Dave Brubeck, Blue is the Sex Pistols, Green is Nickleback and purple is the Stooges.

There been quite a bit of writing about the loudness war. The wikipedia entry is quite comprehensive, with some excellent plots showing how some recordings have had a loudness makeover when remastered. The Rolling Stone’s article: The Death of High Fidelity gives reactions of musicians and record producers to the loudness war. Producer Butch Vig says “Compression is a necessary evil. The artists I know want to sound competitive. You don’t want your track to sound quieter or wimpier by comparison. We’ve raised the bar and you can’t really step back.”

The loudest artists

I have analyzed the loudness of about 15K tracks from the top 1,000 or so most popular artists. The average loudness across all 15K tracks is about -9.5 dB. The very loudest artists from this set – those with a loudness of -5 dB or greater are:

| Artist | dB |

|---|---|

| Venetian Snares | -1.25 |

| Soulja Boy | -2.38 |

| Slipknot | -2.65 |

| Dimmu Borgir | -2.73 |

| Andrew W.K. | -3.15 |

| Queens of the Stone Age | -3.23 |

| Black Kids | -3.45 |

| Dropkick Murphys | -3.50 |

| All That Remains | -3.56 |

| Disturbed | -3.64 |

| Rise Against | -3.73 |

| Kid Rock | -3.86 |

| Amon Amarth | -3.88 |

| The Offspring | -3.89 |

| Avril Lavigne | -3.93 |

| MGMT | -3.94 |

| Fall Out Boy | -3.97 |

| Dragonforce | -4.02 |

| 30 Seconds To Mars | -4.08 |

| Billy Talent | -4.13 |

| Bad Religion | -4.13 |

| Metallica | -4.14 |

| Avenged Sevenfold | -4.23 |

| The Killers | -4.27 |

| Nightwish | -4.37 |

| Arctic Monkeys | -4.40 |

| Chromeo | -4.42 |

| Green Day | -4.43 |

| Oasis | -4.45 |

| The Strokes | -4.49 |

| System of a Down | -4.51 |

| Blink 182 | -4.52 |

| Bloc Party | -4.53 |

| Katy Perry | -4.76 |

| Barenaked Ladies | -4.76 |

| Breaking Benjamin | -4.80 |

| My Chemical Romance | -4.81 |

| 2Pac | -4.94 |

| Megadeth | -4.97 |

It is interesting to see that Avril Lavigne is louder than Metallica and Katy Perry is louder than Megadeth.

The Quietest Artists

Here are the quietest artists:

| Artist | dB |

|---|---|

| Brian Eno | -17.52 |

| Leonard Cohen | -16.24 |

| Norah Jones | -15.75 |

| Tori Amos | -15.23 |

| Jeff Buckley | -15.21 |

| Neil Young | -14.51 |

| Damien Rice | -14.33 |

| Lou Reed | -14.33 |

| Cat Stevens | -14.22 |

| Bon Iver | -14.14 |

| Enya | -14.13 |

| The Velvet Underground | -14.05 |

| Simon & Garfunkel | -14.03 |

| Pink Floyd | -13.96 |

| Ben Harper | -13.94 |

| Aphex Twin | -13.93 |

| Grateful Dead | -13.85 |

| James Taylor | -13.81 |

| The Very Hush Hush | -13.73 |

| Phish | -13.71 |

| The National | -13.57 |

| Paul Simon | -13.53 |

| Sufjan Stevens | -13.41 |

| Tom Waits | -13.33 |

| Elvis Presley | -13.21 |

| Elliott Smith | -13.06 |

| Celine Dion | -12.97 |

| John Lennon | -12.92 |

| Bright Eyes | -12.92 |

| The Smashing Pumpkins | -12.83 |

| Fleetwood Mac | -12.82 |

| Tool | -12.62 |

| Frank Sinatra | -12.59 |

| A Tribe Called Quest | -12.52 |

| Phil Collins | -12.27 |

| 10,000 Maniacs | -12.04 |

| The Police | -12.02 |

| Bob Dylan | -12.00 |

(note that I’m not including classical artists that tend to dominate the quiet side of the spectrum)

Again, there are caveats with this analysis. Many of the recordings analyzed may be remastered versions that have have had their loudness changed from the original. A proper analysis would be to repeat using recordings where the provenance is well known. There’s an excellent graphic in the wikipedia that shows the effect that remastering has had on 4 releases of a Beatles track.

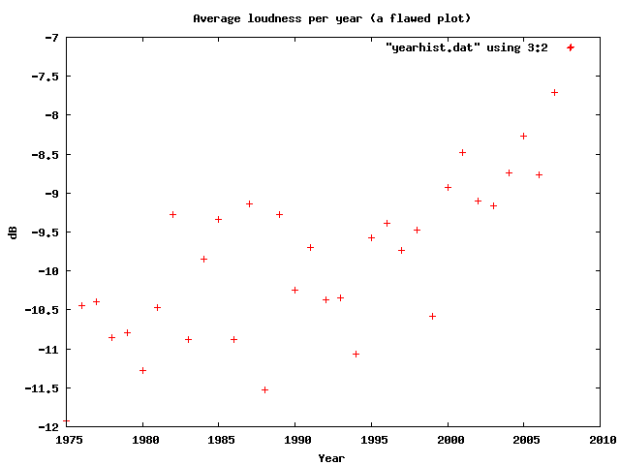

Loudness as a function of Year

Here’s a plot of the loudness as a function of the year of release of a recording (the provenance caveat applies here too). This shows how loudness has increased over the last 40 years

I suspect that re-releases and re-masterings are affecting the Loudness averages for years before 1995. Another experiment is needed to sort that all out.

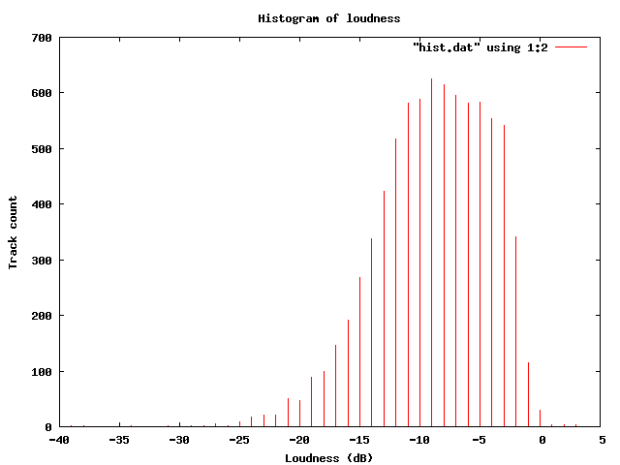

Loudness Histogram:

This table shows the histogram of Loudness:

Average Loudness per genre

This table shows the average loudness as a function of genre. No surprise here, Hip Hop and Rock is loud, while Children’s and Classical is soft:

| Genre | dB |

|---|---|

| Hip Hop | -8.38 |

| Rock | -8.50 |

| Latin | -9.08 |

| Electronic | -9.33 |

| Pop | -9.60 |

| Reggae | -9.64 |

| Funk / Soul | -9.83 |

| Blues | -9.86 |

| Jazz | -11.20 |

| Folk, World, & Country | -11.32 |

| Stage & Screen | -14.29 |

| Classical | -16.63 |

| Children’s | -17.03 |

So, why do we care? Why shouldn’t our music be at maximum loudness? This Youtube video makes it clear:

Luckily, there are enough people that care about this to affect some change. The organization Turn Me Up! is devoted to bringing dynamic range back to music. Turn Me Up! is a non-profit music industry organization working together with a group of highly respected artists and recording professionals to give artists back the choice to release more dynamic records.

Luckily, there are enough people that care about this to affect some change. The organization Turn Me Up! is devoted to bringing dynamic range back to music. Turn Me Up! is a non-profit music industry organization working together with a group of highly respected artists and recording professionals to give artists back the choice to release more dynamic records.

If I had a choice between a loud album and a dynamic one, I’d certainly go for the dynamic one.

Update: Andy exhorts me to make code samples available – which, of course, is a no-brainer – so here ya go: volume.py

The Tagatune Dataset

Edith L.M. Law has just released the long-awaited Tagatune Dataset.

From the README:

The Tagatune dataset consist of 31383 music clips that are 29 seconds long, created from songs downloadable from Magnatune.com. The genres include classical, new age, electronica, rock, pop, world, jazz, blues, metal, punk etc. The dataset is optimized for training machine learning algorithms — i.e. it includes tags that are associated with more than fifty songs, and each song is associated with a tag only if that tag has been generated by more than two players independently.

The data is collected from a two-player online game called Tagatune, deployed on the GWAP.com game portal. In this game, two players are given either the same song or different songs, and are asked to enter descriptions appropriate for their given song. After reviewing each other’s descriptions, the players then guess whether they are given the same song or not.

This is great data, useful for all sorts of things, especially research around autotagging and query-by-description. It is quite complimentary to a dataset that we are about to release from the Echo Nest (stay tuned for that).